A prodigious moonfish

Here’s the next instalment of my Clark Ashton Smith read-through. These nine stories take us from June to November of 1932, at a rate of roughly two stories per month.

From what I understand, Smith would have been paid around 1c/word for these stories, which would work out to a range of US$1,000-$1,600 per story in today’s money. So, working at this prolific rate, one can imagine Smith earning a monthly income that was possibly enough to live off, but by no means abundant.

“The Invisible City” (June 1932)

Some explorers lost in the desert stumble across an invisible city populated by invisible aliens. So, yes, the story certainly delivers on its title in the most basic sense. But the aliens here are just too incompetent to elicit any real horror. Right after capturing the human protagonists, the aliens take them to see the magic crystal that sustains their entire civilisation. “Yep, here's our VERY IMPORTANT, LOAD-BEARING crystal. It sure would be a shame if anyone damaged our IRREPLACABLE AND EXTREMELY FRAGILE crystal. That would absolutely suck…”

2/5

“The Weird of Avoosl Wuthoqquan” (June 1932)

“Weird” in this context is being used in its original meaning of “fate, destiny”, after the Old English wyrd and Old Norse urðr. The titular Wuthoqquan, like so many of Smith's characters, is doomed from the very beginning.

This etymology suggests a whole different way of looking at “weird fiction” in general: that the key ingredient is not the depiction of things strange or uncanny, but rather the “fatedness” of characters and events. The fatalistic theme is certainly central to many of the great works of the genre, from Thomas Ligotti to Caitlin R. Kiernan to Brian Evenson. And certain “weird” stories can offer fatalistic horror without involving any supernatural elements, as in Melanie Tem's devastating “Dahlias”. One could also readily draw a connection to the structural aspects of weird fiction: the refusal of plot movement or character development. In the realist tradition, the purpose of a short story is to illuminate a moment of personal realisation or change. As George Saunders puts it, the story must end at the point where the author can say: “After that, nothing was ever the same again.” The weird tale, by contrast, rejects development. Everything is already there when the story begins, already fated, and all that must take place is the revelation of that fate through successive layers of atmosphere and imagery. Nothing actually “happens” in the story; at most the character comes to understand something that has been true all along (think, for instance, of how many Lovecraft stories derive their twist from the protagonist uncovering a latent horror that has been present from the start). Can we say, then, that the defining characteristic of weird fiction is not the presence of ghosts, ghouls or tentacled horrors, but this sense of fatedness, this wyrd?

Anyway. What was I talking about? Oh yes, this story is pretty good. It's about a guy who gets eaten by giant spider.

4/5

“The Letter from Mohaun Los” (August 1932)

Following on from “The Eternal World”, this story uses the same premise of “guy sits in a time capsule and sees a bunch of cool stuff without interacting with any of it”. But this story is over twice as long as “The Eternal World”, and the cool stuff… isn't really that cool. The overall effect is similar to having someone show you photos from their holiday. Not good.

1/5

“The Maker of Gargoyles” (August 1932)

As I noted in the first post of this series, Smith's artistic pursuits extended to poetry and sculpture as well as fiction. So whenever a poet or sculptor appears in his stories, I suspect a self-insert. But if the title character of this story is a self-insert, he reflects only the worst aspects of the author. He’s a medieval incel-type, both hated and hateful. And this character, in turn, puts the worst of himself into his art, creating two gargoyles that come to life and terrorise the town.

The gargoyles represent, respectively, the sculptor’s hatred of a community that shuns him, and his frustrated lust for the woman he desires. Eventually they act out these repressed desires directly, in a stomach-turning scene of slaughter and rape. But the sculptor himself is unaware of the connection, and is about as horrified as anyone by what his art ends up accomplishing. So are the gargoyles really “him”? Are we our darkest desires, or the better selves that restrain them?

4/5

“The Empire of the Necromancers” (September 1932)

This story is just fucking awesome.

5/5

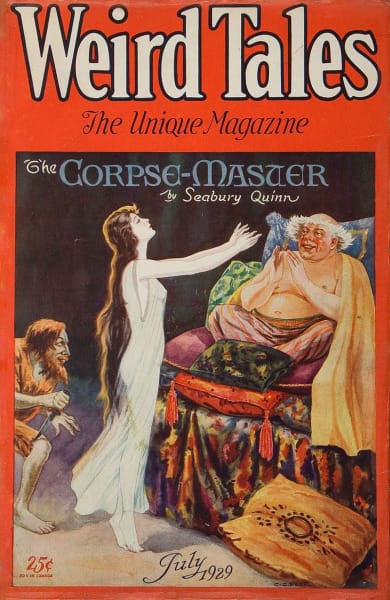

“The Hunters from Beyond” (October 1932)

We've got a self-insert two-for-one in this story, which is about a weird fiction writer who goes to visit his cousin, a sculptor of grotesque and macabre statuary. The cousin has figured out how to see into other dimensions, allowing him to sculpt his monstrous figures “from life”. This doesn’t end well for him.

It's tempting to read the two artists in this story as two different aspects of Smith's psyche. But if so, the fiction-writer is no more than a passive observer, looking on without agency as his darker half plunges literally into Hell for the sake of his art.

4/5

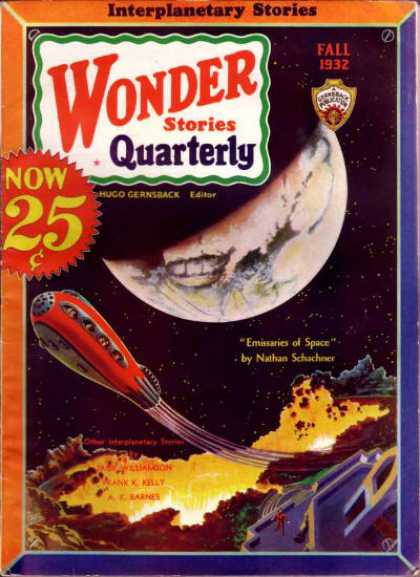

“Master of the Asteroid” (October 1932)

Most of Smith's sci-fi stories are straightforward pulp, in which foreign planets are merely stand-ins for foreign countries, and the technical challenges of space travel are glossed over or outright ignored. This piece is something quite different: a much darker, colder form of science fiction, like a distant premonition of the deep space horror that would one day be written by the likes of Peter Watts or Cixin Liu.

Here, outer space is “the inconceivably hostile environment of a cosmos not designed for men”. Colonists trying to survive on Mars suffer “irrational animosities, manias or phobias” due to the alien environment. One character even speaks of “the torment of human consciousness”— a Wattsian phrase if ever there was one.

The late introduction of alien bug people and other weird creatures somewhat spoils the desolate atmosphere, but this is still a powerfully prescient story.

3/5

“The Testament of Athammaus” (October 1932)

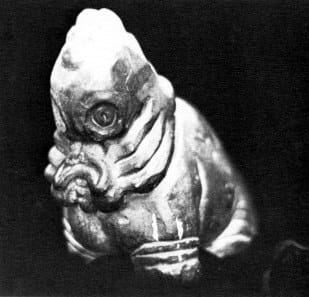

One of several Smith stories set in the prehistoric world of Hyperborea. In this one, a royal executioner recounts his efforts to behead the notorious bandit, Knygathin Zhaum, who is “related on the maternal side to that queer, non-anthropomorphic god, Tsathoggua”.

Every time Athammaus executes Zhaum, he returns the next day, like a malevolent Bugs Bunny tut-tutting at Elmer Fudd. The executioner’s escalating efforts to permanently kill his prisoner walk a narrow line between horror and farce.

4/5

“The Dimension of Chance” (November 1932)

Unusually for Smith, this story begins with a concrete prediction of future history. The year is 1975, and America is at war with the “Sino-Japanese Federation”, who have recently occupied San Francisco. None of this matters very much, because within a few pages the American and Japanese soldiers have pursued one another through a wormhole into another dimension.

The general theme of this dimension is that no two things in it are alike. Every plant is “a species in itself”. The very soil is endlessly varied, “a remarkable mosaic of numberless elements”. And as for the local fauna:

...there was no common norm or type of development as in the terrestrial species. Some of the entities were no less than twelve or thirteen feet tall; others were squat pygmies. Limbs, bodies, and senseorgans were equally diversified. One creature was like a prodigious moonfish mounted on stilts. Another was a legless, rolling globe fringed about the equator with prehensile ropes that served to haul it along by attaching themselves to projections. Still another resembled a wingless bird with a great falcon beak and a tapering serpentine body with lizard legs, that glided half-erect. Some of the creatures possessed double or triple bodies; some were hydra-headed, or equipped with an excessive number of limbs, eyes, mouths, ears and other anatomical features.

All this is fantastic good fun. The plot is a bit ramshackle toward the end, but who needs a plot when you have such a high concentration of Weird Little Guys?

4/5

That’s all for this month. See you next time.

Member discussion