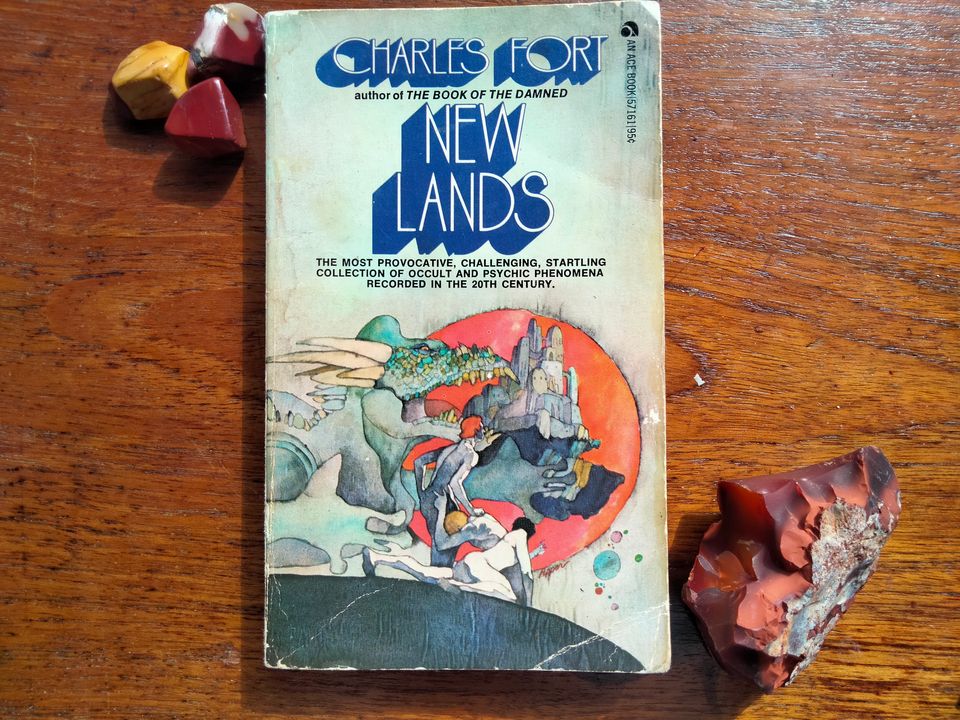

An Alternative Cosmos: Charles Fort's "New Lands"

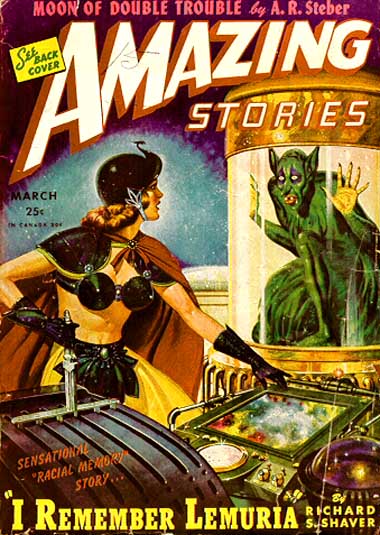

Since the beginning of this blog, I’ve hoped to include occasional detours into the world of fringe writing—UFOs, cryptids, conspiracy theories—alongside the sci-fi and fantasy that is my bread and butter. The boundary between these genres has often been quite thin. Science fiction influences pseudoscience, and vice versa. Books in both categories contain many of the same elements: spaceships, monsters and psychic phenomena, to name a few. They also often make use of similar graphic design, as you can see above. Holding a book in your hand, you might not immediately be sure which kind it is.

In some cases, the borders have been even more slippery. The horror novelist Whitley Strieber wrote about his own alien abduction experiences in the bestselling Communion (1987). Richard Sharpe Shaver’s visions of subterranean torture chambers were published as fact in the science fiction magazine Amazing Stories. And of course, L. Ron Hubbard had a successful career as a pulp writer before he became the founder of Scientology.

Charles Fort came before all these. He is often considered the grandfather of all “alternative researchers”; he popularised many concepts that would go on to become mainstays of the genre, from psychic powers to alien visitations.

Perhaps more importantly, though, Fort presented a particular way of thinking about the world: a combination of radical skepticism toward authority with a fierce faith in one’s own ability to research and synthesise data. “Doubt everything, but trust yourself.” This epistemic stance continues to underpin fringe theories to this day, from ufology and cryptozoology to Flat-Earthism and the Tartaria conspiracy theory.

New Lands (1923)is Fort’s second book, and is mainly concerned with astronomy. It begins with a long, scathing attack on the academic consensus of the day, highlighting alleged flaws in logic that show the mainstream understanding of outer space to be hopelessly flawed. This is followed by a catalogue of anomalies in the sky, things that science cannot explain, including appearances of what we would now call “UFOs” but Fort rather charmingly describes as “airships”. (Likewise, his visitors from other planets are not “aliens” but “extra-mundanians”.)

Fort’s writing style is dense, aggressive, alternating between dull recitations of evidence and surprising bursts of poetry. See him here, raging against the “dragons” of scientific ignorance:

Phantom dogmas, with their tails clutching at vacancies, are coiled around our data.

Serpents of pseudo-thought are stifling history.

They are squeezing "Thou shalt not!" upon Development.

New Lands—and the horrors and lights, explosions and music of them; rabbles of hellhounds and the march of military angels. But they are Promised Lands, and first must we traverse a desert. There is ahead of us a waste of parallaxes and spectrograms and triangulations. It may be weary going through a waste of astronomic determinations, but that depends—

Or here, attacking the astronomical method of triangulation as a “false god” to be thrown down:

Triangulation that, according to his little priests, straddles orbits and on his apex wears a star—that he's a false Colossus; shrinking, at the touch of data, back from the stars, deflating below the sun and moon; stubbing down below the clouds of this earth, so that the different stories that he told to Aristarchus and to Newcomb are the conflicting vainglories of an earth-tied squatter—

The blow that crumples a god:

That, by triangulation, there is not an astronomer in the world who can tell the distance of a thing only five miles away.

At times he has command of an acidic wit, even when the arguments he’s putting forth are totally incorrect. Considering two consistent methods of calculating the speed of light, he dismisses them as “no more than the reekings of two consistent stenches”. And later, discussing unidentified lights in the sky: “The appearances over Liverpool and over towns in Wales might be attributed to German airships by someone who has not seen a map since he left school.”

Of course there’s schadenfreude in reading this today. Basically all of Fort’s claims have been proven completely wrong. With the benefit of a whole century’s hindsight, we can watch Fort make a fool of himself over and over again. He mocks a 19th-century astronomer for being so confident as to calculate the distance of the sun as 95 million miles. (The real distance is about 93 million.) He also makes great sport of those who predicted the Leonids meteor storm would return every 33 years. British and American astronomers were embarrassed when the storm failed to appear in 1899, and could resort to no explanation other than cloudy skies. Fort takes this as emblematic of scientists’ tendency to sweep their failed predictions under the rug. (The Leonids returned in 1966 and 1999, proving the 19th-century calculations essentially correct.)

Fort is a unique writer, not a good one. Despite the small pleasures of his wit and whimsy, overall the book is a chore to read. There is no sense of structure of progression. The text drifts aimlessly from one subject to another, and returns obsessively to a few motifs: stones falling from space, detonations in the sky, and unidentified lights among the stars. Page after page is filled with repetitious accounts of these phenomena. Individually they are neither interesting nor particularly “inexplicable”, but presenting them in such vast numbers gives them a certain superficial veneer of plausibility: there are so many of these stories, surely some of them must be real?

This style of argumentation will be familiar to anyone who has read UFO literature, watched faux-scientific TV shows like Ancient Aliens, or scrolled through conspiracy TikTok. Rationalists call this the “gish gallop” and treat it as an unfair debate tactic. But it also reflects something deeper about the mindset behind “alternative science”. Fort’s way, which has been adopted by countless others, is a non-linear way of understanding the world. Everything is connected, so everything must be presented all at once. The truth is not revealed step by step, in the tradition of Aristotelian logic. Instead it emerges spontaneously from a web of inferences, all focusing on the same point: revelation! Taken to its furthest extreme, this is the mindset of the psychedelic experience, and the psychotic break.

Another feature of this non-linear mindset is the focus on implication over definitive claims. Conspiracists are often cagey about revealing exactly what they believe, and Fort is no different. He never outright describes his own model of the solar system, but reveals it gradually through hints and allusions.

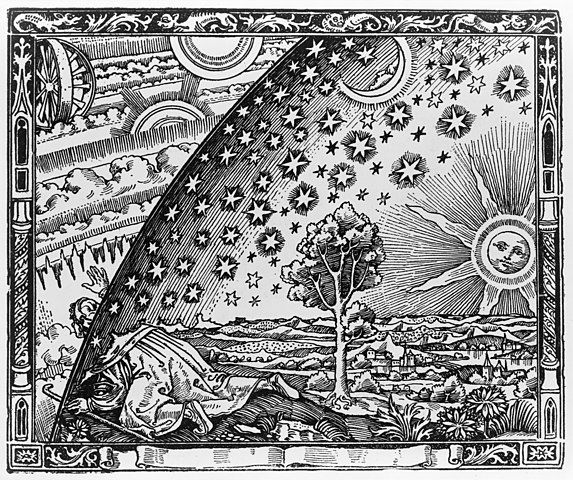

Fort posits a geocentric universe. His Earth is stationary, orbited by much smaller planets, moon and sun. Compared to the vast blackness of space that we now know to be real, Fort’s cosmology feels positively cosy. His moon is only 100 miles in diameter. His Martians and Venusians visit the Earth in glowing airships whenever their planets draw near. Discussing the distances in outer space, he writes that the challenge for future space travellers will be “not how to reach the planets, but how to dodge them.” Even the stars are not very far away in Fort’s world, and like certain Medieval scholars, he imagines them as pinholes in a great dark shell.

One idea that Fort returns to repeatedly is that outer space contains “currents” or “pressure differentials” which may spontaneously suck up matter from one world and deposit it on another. As evidence of this he cites vast boneyards in Siberia and Colorado which, he claims, must have been formed by animals deposited there from other worlds. Conversely, the abrupt decline of the Classic Maya civilisation (an ongoing archaeological mystery) is explained as the people being whisked away on a cosmic whirlwind:

Lost tribes and the nations that have disappeared from the face of this earth—that the skies have reeked with terrestrial civilizations, spreading out in celestial stagnations, where their remains to this day may be. The Mayans—and what became of them? Bones of the Mayans, picked white as frost by space-scavengers, regioned to this day in a sterile luxuriance somewhere, spread upon existence like the pseudo-breath of Death, crystallized on a sky-pane…

Likely enough, or not quite likely enough, one of these earlier Egypts was populated by sphinxes, if one can suppose that some of the statuary still extant in Egypt were portraitures… One conceives of their remains, to this day, wafting still in the currents of the sky: floating avenues of frozen sphinxes, solemnly dipping in cosmic undulations, down which circulate processions of Egyptian mummies.

Animals falling from the sky was apparently a special fixture of Fort’s imagination. The image has been picked up by generations of writers, and has come to serve as a symbol for inexplicable events in general. It was used in this sense in the “rain of frogs” scene in Paul Thomas Anderson’s Magnolia (1999), and more recently, in the shower of gore that falls from the sky in Jordan Peele’s Nope (2022).

Fort’s obsession over this motif gives rise to one of the most lovely passages in New Lands:

… torrents of dinosaurs, in broad volumes that were streaked with lesser animals, pouring from the sky, with a foam of tusks and fangs, enveloped in a bloody vapor that was falsely dramatized by the sun, with rainbow-mockery. Or, in terms of planetary emotions, such an outpouring was the serenade of some other world to this earth. If poetry is imagery, and if a flow of images be solid poetry, such a recitation was in three-dimensional hyperbole that was probably seen, or overheard, and criticized in Mars, and condemned for its extravagance in Jupiter. Some other world, meeting this earth, ransacking his solid imagination and uttering her living metaphors: singing a flood of mastodons, purring her butterflies, bellowing an ardor of buffaloes. Sailing away—sneaking up close to the planet Venus, murmuring her antelopes, or arching his periphery and spitting horses at her—

It’s balderdash, yes, but enchanting balderdash. It makes one wonder at what could have been, if Fort had turned his pen toward fiction instead of dubious fact.

Fort really was a gifted writer, albeit very intermittently. In between the laborious accounts of extra-mundanian activity, there are moments throughout the book where his ultra-skepticism briefly feels convincing. One is swept up, for a moment, in a fugue of uncertainty. Wait, maybe Uranus really isn’t a planet? How would we know? What if this whole “science” thing really is a just house of cards, propped up by confirmation bias and institutional inertia?

Fort’s central criticism of mainstream astronomers is that they trumpet their successes while quietly ignoring their failures. This feels pretty prescient in light of the ongoing replication crisis afflicting psychology, medicine and adjacent fields. Fort’s skeptical viewpoint offers a timely reminder that science is not a machine that spits out truth, but an institution made up of fallible human beings.

Take that skepticism to its furthest extreme, and you become a conspiracy nut, an anti-vaxxer, a Flat Earther. But a little bit is eminently healthy. Over the past decade, governments and businesses invested millions of dollars in applying “nudge theory”, the new hotness in behavioural economics—but last year a meta-analysis found that, after accounting for publication bias, the underlying research might not actually demonstrate any effect at all. Perhaps if they’d had a Charles Fort nipping at their heels, they might have noticed a little earlier.

Fort occasionally hinted that he himself didn’t believe his own claims; that he was merely a gadfly trying to deflate the pompous self-assurance of the scientific mainstream. “All organisations of thought must be baseless in themselves, and of course be not final,” he writes in New Lands. “One who searches for fundamentals comes to bifurcations; never to a base; only to a quandary.” But whether this is the sagacity of an early postmodernist, or the defensive posture of a crank, I will leave to the reader to decide.

Member discussion