Dark Flowers of the Pulp Age

Clark Ashton Smith is my favourite short story writer. I would never claim that he's the best short story writer (that's Chekhov, naturally). But he's my guy. There is something about his brand of florid, effervescent horror that I find quite comforting, and I return to him often when I'm feeling uninspired to read.

But Clark Ashton Smith wrote a lot of stories. I haven't even come close to reading them all! A while back, on the short-lived social network Cohost, I started documenting my progress through the Smith canon in chronological order. Cohost is shutting down at the end of the year (goodnight, sweet prince) so I'm restarting my review journey over here.

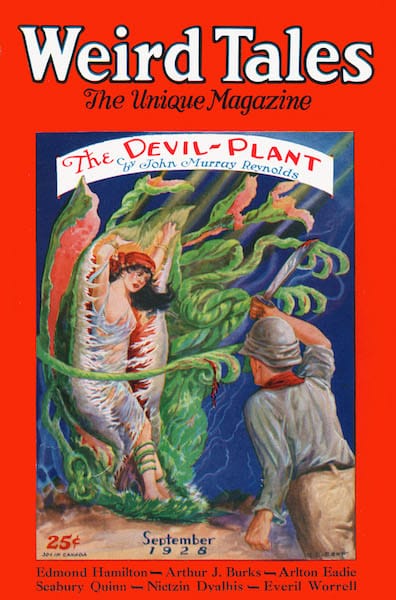

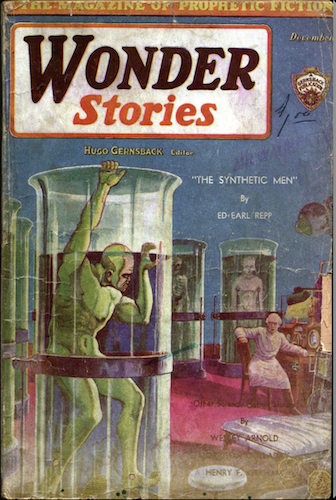

Many of my readers will already be familiar with Smith, but if you aren't, here's a brief introduction. Smith was a prolific short fiction writer in the 1930s, selling stories to pulp fantasy and horror magazines like Weird Tales and Wonder Stories. He shared magazine space with H. P. Lovecraft and Robert E. Howard, and although the three of them never met, they frequently wrote to one another.

But while Lovecraft single-handedly invented the genre of cosmic horror, and Howard arguably did the same for sword and sorcery, Smith never had such an overt influence on later writers—perhaps because his prose is, as Gene Wolfe put it, "literally inimitable". Even more so than Lovecraft, it is impossible not to recognise Smith's style once you know it. His writing is characterised by archaic language, lush purple prose, and a sense of cosmic horror tinged with absurdity. Unlike the po-faced Lovecraft, Smith's stories are often surprisingly funny.

The strange thing about Smith is that he didn't really consider short fiction to be his calling, just a way to pay the bills. He believed his true artistic work was poetry and, later, sculpture. This mercenary attitude meant that he wrote every genre that would sell: sci-fi, fantasy, ghost stories, historical adventure. Yet he invests all these genres with the same sense of cosmic melancholy, so that they all seem to exist within a single literary universe, even when they contradict each other on the details.

There are over 100 Clark Ashton Smith stories listed in his bibliography (compare ~70 for Lovecraft and 300+ for Howard). All of them can be found at eldritchdark.com, so you can read along with me if you like. When we get to the end, I'll cap it off with a look at the one play that Smith wrote, which bears the incredible title of The Dead Will Cuckold You.

The images in these posts will be either a) covers of the magazines Smith published in, or b) pictures of Smith’s sculptures, which were his main creative focus in the latter part of his life.

“The Abominations of Yondo” (August 1926)

This story is to weird fiction what the Fleischer Brothers’ “Swing You Sinners” is to cartoons. In the year 1926, plot had not yet been invented, so the whole story is just a guy walking around looking at fucked up stuff. And really, what more do you need?

4/5

“The Ninth Skeleton” (September 1928)

A short and unsatisfying sketch that nevertheless introduces several themes Smith will return to across his career: the Californian landscape, portals between dimensions, and of course, skeletons.

2/5

“The End of the Story” (May 1930)

This is the first of many Smith stories set in the fictional medieval province of Averoigne. But here Averoigne is not yet fully formed. The prose is somewhat thin, the setting lightly sketched.

In the later Averoigne stories, Smith takes great pleasure in depicting Christian faith as metaphysically weak and ineffective. Prayers are shown to be useless against demons; monks are corrupted by sin; and in the climax of the masterful “The Colossus of Ylourgne”, an entire monastery is shat on by a giant. By contrast, “The End of the Story” takes a more traditional tack. It is the secular nobleman who falls to corruption, while the wise abbot rescues him, and the monster is driven off (temporarily, at least) by the touch of holy water.

2/5

“The Last Incantation” (June 1930)

Smith anticipates The Mezzanine in this short piece that takes place entirely inside the wandering mind of a sad wizard as he sits on his wizard throne.

3/5

“Sadastor” (July 1930)

If Smith had ever had kids and told them a bedtime story, it might have come out something like this. It's a gloomy, yet cosy fable, told by a spacefaring demon to a weeping lamia “in those years when the sphinx was young”. This is the first story in which Smith really lets his prose off the leash, and it is an absolute joy to read.

5/5

“The Phantoms of the Fire” (September 1930)

Gene Wolfe, in an introduction to a posthumous collection of Smith's stories, speculates that the reason Smith turned to writing fiction was primarily financial. We know that Smith considered his poetry and sculpture work to be more important and artistically serious than his short stories. Wolfe goes further in pointing out that the period of Smith's prolific story-writing, from 1930 to 1935, coincides closely with the aftermath of the Wall Street Crash of 1929. Wolfe's conclusion is that Smith was independently wealthy, living for most of his life on stock dividends, and the temporary cessation of dividend payments was what forced him to write for money.

The varying styles of these early stories seem to support Wolfe's theory. We've already had a medieval story, a high fantasy piece, and some psychedelic horror. This one is a more traditional ghost story, and the next is science fiction. It feels like Smith is testing different genres, trying to figure out what he can sell and what he enjoys writing.

Anyway, I'm glad he didn't end up focusing his career on ghost stories, as I find them unbearably tedious, and this one is a particularly pointless example.

1/5

“Marooned in Andromeda” (October 1930)

I absolutely love it when vintage sci-fi stories project their own assumptions about technology into the distant future. So I broke into a big grin when the protagonists of this story—after travelling to another galaxy and being marooned on an alien world—set about judging the length of the planet's day/night cycle by winding their pocketwatches.

This is Smith's first attempt at two-fisted pulp science fiction, and at times it feels almost like self-parody. The three heroes approach their dire situation with all the pluck and vigour of an overgrown boy scout troop. After being chased by tribesmen into a pitch-black stinking cave, one of them utters the amazingly bathetic phrase: "Phooey! This is worse than Gorgonzola and fox-guts all in one." And later, when they have all been swallowed alive by a giant alien pelican: "Even a fiction-writer wouldn't dare imagine this!"

Still, the piece picks up steam as it goes along, and the final scene offers a small glimpse of the uncanny horror that Smith will later perfect in sci-fi stories like “The Vaults of Yoh-Vombis” and “The Dweller in the Gulf”.

3/5

“Murder in the Fourth Dimension” (October 1930)

A nasty little revenge tale in which the whiz-bang marvels of the Edisonade are turned toward the darkest and pettiest of human ends. The premise is a little thin (you can probably guess everything that's going to happen after the first page or so) but the final image is haunting; it can be read both as a moral comeuppance or a meaningless cosmic joke.

2/5

“The Uncharted Isle” (November 1930)

A brief, dreamlike story of a castaway lost among people who cannot see or hear him. The motif of a character “adrift in time” is another that will recur several times in other Smith stories.

2/5

“The Necromantic Tale” (January 1931)

The premise of this story is extremely cool: what if you got so absorbed in a book that you were quite literally trapped there? Like Zhuangzi dreaming of himself as a butterfly, the protagonist of this piece is forced to ask: "Am I a 20th century gentleman reading about a 15th century warlock? Or am I a 15th century warlock dreaming himself as a 20th century man?"

Smith's prose is a little flat here, and the appearance of demons and witches feels merely obligatory. But the wit of the premise more than makes up for it.

4/5

“An Adventure in Futurity” (April 1931)

Is it possible for a writer to be racist against beings who don't actually exist? Smith tries his hardest to answer 'yes' in this ugly, unpleasant time travel story, which depicts a far future in which the human race has become "effete and effeminate". The future humans have all their manual labour done by Venusian slaves, who are "primitive", "ferocious and intractable" and "breed with the most appalling fecundity, in opposition to the dwindling numbers of the human race". Meanwhile, the inscrutable, froglike Martians are plotting behind the scenes, fomenting rebellion among the Venusian slaves (who of course are too "savage" to conceive of any such strategy by themselves).

The story isn't all bad; there are flashes of genuine horror in the last act as the human race succumbs to a series of extraterrestrial bioweapons. But these moments can't make up for the fact that the whole thing feels like something Nick Fuentes dreamed about after drinking too much cough syrup.

2/5

That's all for this round. Most of these early stories are not the best of Smith's work, so it may seem like I'm just beating up on the poor guy. But we are going to get to the good stuff soon.

Member discussion