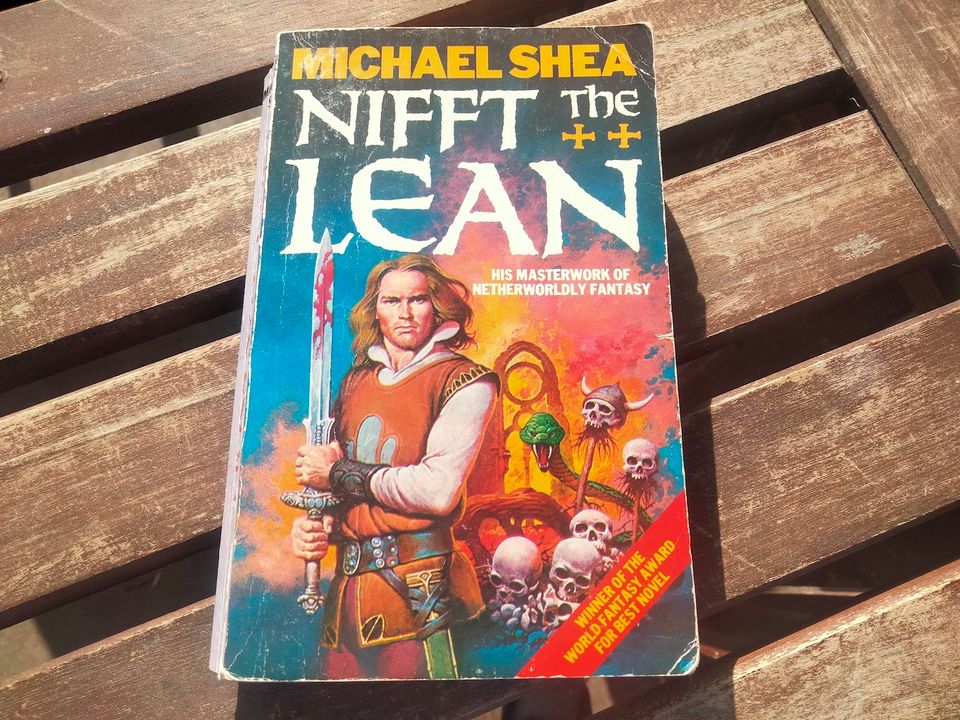

Go Directly To Hell: Michael Shea’s “Nifft the Lean”

First, some exciting news. I’ve got a new short story, “Among the Birds”, which is now free to read in the latest edition of Mysterion magazine. It’s an existential horror story of sorts, about a human soul who has been sent inexplicably to a Hell for birds.

As a tie-in with the story, this month I’m reviewing one of my favourite Hell-themed books: the 1982 sword and sorcery collection Nifft the Lean. Enjoy!

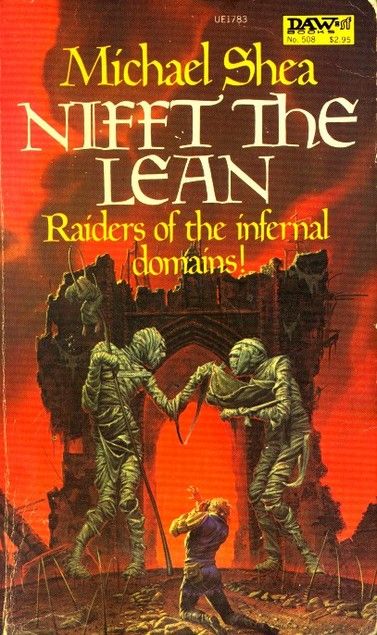

Michael Shea’s Nifft the Lean, though sometimes billed as a novel, is really a collection of four short stories featuring the title character. Nifft is a wandering thief and adventurer, clearly modelled on classic characters like Fritz Leiber’s Grey Mouser, Jack Vance’s Cugel the Clever, and R. E. Howard’s Conan the Cimmerian. While Shea does his best to imitate those writers, he never manages to achieve the same heights of wit, whimsy and adventure. But there is one thing he does better than any of them: he writes absolutely face-melting descriptions of nightmare hellscapes and supernatural gore.

Not for nothing does the book’s back cover proudly proclaim it as “Shea’s Inferno”. Another reviewer compared it to Hieronymous Bosch’s Garden of Earthly Delights. For myself, I was reminded of the brutality and campiness of a death metal album cover. It’s a parade of horrors so extreme that it becomes not actually horrifying, but richly satisfying.

Of course, not everyone has a palate for this stuff, so here I’ll issue a content warning: the rest of this review contains quotes from scenes of gore, mutilation, torture, and basically every other fucked up thing you can think of. You have been warned.

Taken as a novel, Nifft the Lean does not put its best foot forward. It begins with not one but three prologues—two separate introductions by the tedious historian Shag Margold, then a frame narrative that basically amounts to Nifft telling his friend “Let me tell you a story…” Finally on page 21 we reach the actual start of the first story, which has the extravagant title of: “Come Then, Mortal—We Will Seek Her Soul”.

Shortly into this piece, we get our first taste of the grotesque imagery that Shea can bring to bear, as Nifft is accosted by a maggot-riddled skeleton crawling from the bowels of the earth:

…Flesh had begun to web and drape the bones. Not flesh, mind you - but just such gluey rags as comes before it's utterly gone. This foul paste spread. Lumps of it rose within the ribs’ cage like loaves in an oven, and the festoons on the rest of the skeleton thickened, and wove, and knit into skin. And that skin began to stir, and then to crawl, and then to boil - with worms.

[…]

The twisting maggots covered it so thick that it shed clumps of them as the swimmer might shed the foam he’s crawled from. The worms dripped, and then drained down. Here and there they fell away completely, and left patches of fresh, pale skin. Over the ribs they rose in a pair of squirming domes, and then avalanched away and left behind two fat, rose-nippled breasts as luminous as full moons. And at the same time, luscious thighs and loins shed their foulness and glowed, and her skull sockets spilled out their contents as great black eyes filled them.

This passage also highlights one of Shea’s less endearing qualities: his descriptions of women.

To be fair, all the women who appear in the novel (including a vengeful ghost, a vampire queen, and a renegade prophetess) are powerful, self-willed and charismatic figures. Unfortunately, this is somewhat undercut by them nearly always being naked. Their bodies are lovingly described with such phrases as “fat paps”, “hips like a vase for milk”, and “big guava breasts, hanging-ripe”. Like the gore, these descriptions are so exaggerated that I found them more funny than offensive, but again, tastes may vary.

Having reconstituted herself, the corpse-woman offers Nifft and his companion a quest: to seize the lover who betrayed her in life and carry him down to Hell so she can wreak her vengeance upon him.

Before we can actually get to Hell there is a lot of work to be done in capturing the lover and opening the gateway. Most of this isn’t terribly interesting. It’s all imitation Vance with twice the verbiage and half the wit. I did find it striking that the method of getting to Hell—hanging around a dying person and grabbing hold of Death when he comes to claim them—is almost exactly the same as in the last book I reviewed.

Nifft manages to best Death in a wrestling match and wins the right to enter Hell while still alive. Now, finally, the face-melting can begin.

To take the musical analogy further: if the rest of the story was verse and chorus, then this is the extended guitar solo. The plot falls away, and for a good 15 pages it’s nothing but two guys walking through Hell looking at fucked up stuff.

And what stuff it is! If I quote to you descriptions of diseased crones whose stench is “charnel house mixed with the smell of a brothel’s slop room”; or if I mention the “crabs with human lips” who torment “men whose legs fused and tapered to a stem…with their brains branching out above them like little trees”; or if I write of “ghoulish smithies… where giants with pipes blew screaming dwarves into being from cauldrons of molten flesh”; or even if I quote at length the fate of this poor bastard:

Another man who ran in delirium was chased by several apothecaries. He was nude, straight from his bed, and as he fled, huge swellings in his groin and neck split open. Wet young wasps the size of doves crawled out of them and clung to his body, waving their wings to dry them.

…then I have still only hinted at a fraction of the phantasmagoric images that crawl across page after page of this luxuriously horrifying sequence.

After the heights of the first story, the second piece, “The Pearls of the Vampire Queen”, is rather thin and disappointing. There are no netherworlds here, only a rather convoluted heist. The star of this tale is undoubtedly the titular Vampire Queen, who is basically a walking Frank Frazetta painting, with the suitably ridiculous name of Queen Vulvula. Aside from her, the story is fairly bland but agreeably short.

The third and longest story is a return to form—and to Hell. “The Fishing of the Demon Sea” sends Nifft and his friend Barnar down to a new underworld, one that’s subtly different from the first story. The Demon Sea is not an afterlife, but a subterranean ecosystem of torture and degradation. Its denizens derive their sustenance from human suffering. Thus, living captives from the surface world are a universal resource that the demons constantly struggle for control over.

Here human bodies are put to a thousand terrible uses: fused with parasitic sea corals, devoured by aquatic wasp larvae, or enslaved in underwater construction projects. But the most creative tortures are worked by demons “of the class whose use of man is artistic rather than anthropophagous”:

…these steaming ramparts were the matrix for human bas-reliefs, wherein the living material, variously amputated, were cemented to compose a writhing mural. The innards of these sufferers were grafted to a system of blood-pipes set in the scalding masonry so that, once troweled and tamped into place, they lived rooted, sustained by that vascular network of boiling blood.

Nifft and Barnar decide they need a local guide through this terror-world. This leads them to the novel’s absolute best character: Gildmirth the Privateer.

Gildmirth is an immortal, shapeshifting wizard-pirate who has lived on the Demon Sea for centuries. Here he indulges his obsession with zoology by capturing sea-fauna and maintaining them in a huge open air aquarium. He lives in a flooded mansion full of rotting paintings of himself, where he is eternally haunted by a demon octopus that wants to drive him insane. He eats gold and jewels. He can turn into a giant lizard. Ah, I could write a whole post on Gildmirth alone, he’s so cool! The only problem is that he highlights how dull the actual protagonists are by comparison.

As with the first story, the Demon Sea contains too much insane horror for me to quote it all, and I wouldn’t want to spoil it anyway. I will reluctantly pick just one more passage to share. It’s an incident from the heroes’ homeward journey, in which they face a storm of burning flesh and body parts:

Flesh was the universal material of that jumbled terrain, knit of welded bodies both human and demonic, and all that flesh was toweringly aflame. Crazed, veering winds raised the flame into peaks and harvested it, tearing it up by its sizzling roots of skin and blowing flesh and flame alike to rags and tatters that came driving at you like a blizzard. The living fuel sundered, body fragments wheeled before the gale till they were re-welded by impact against the first feature of that landscape that intercepted their flight, while roaring within the roaring of the fire were these victims' million voices, which rose in grieving unison, intact above their molten, broken bodies.

[…]

We had to run as much as possible against the wind in order to keep our shields between us and the burning flesh. This, when it struck us, clung to us - sometimes in the most literal way when hands, claws or entire limbs of it hit us and tried to wrestle the shields from our grips, and wherever that flesh touched ours, ours came away.

Dante himself couldn’t have done it better.

The last story in the collection, “The Goddess in the Glass”, is another damp squib. It’s a tedious tale of city politics and engineering projects, which even the late appearance of a giant robot skeleton can’t do much to enliven. Nifft is hardly even present in this one. I strongly suspect this was originally an unrelated story, which Shea rewrote to pad out the page count.

It’s a sad end to a book that is intermittently really fucking awesome. But isn’t that the way with music albums, too? The last track is always some half-baked shit that most people aren’t going to listen to.

Availability

Unfortunately, this book is out of print and rather rare. The cheapest copy online is around $35 US (which makes me feel slightly smug about finding it years ago for $3 in a charity shop). There is no ebook version.

For those who do acquire a copy, I encourage the following reading strategy. Skip all the prefaces by Shag Margold, which are boring. Relish “Come Then, Mortal” and “The Fishing of the Demon Sea”. Read “Pearls of the Vampire Queen” if you like, but feel free to skip it. Do not bother with “The Goddess in the Glass” unless you are a completist or really like descriptions of earthworks.

Further Reading

- Cartoonist Michael de Adder draws a touching graphic memorial to Charles Saunders, a pioneering Black author of sword and sorcery.

- At Blood Knife, Sean T. Collins gives a great introduction to The Black Company novels in the context of working class life.

Don't forget, you can find me on Twitter @roguesrepast, on Bluesky @gnipahellir.bsky.social, or email me at paperbackpicnic@gmail.com.

Member discussion