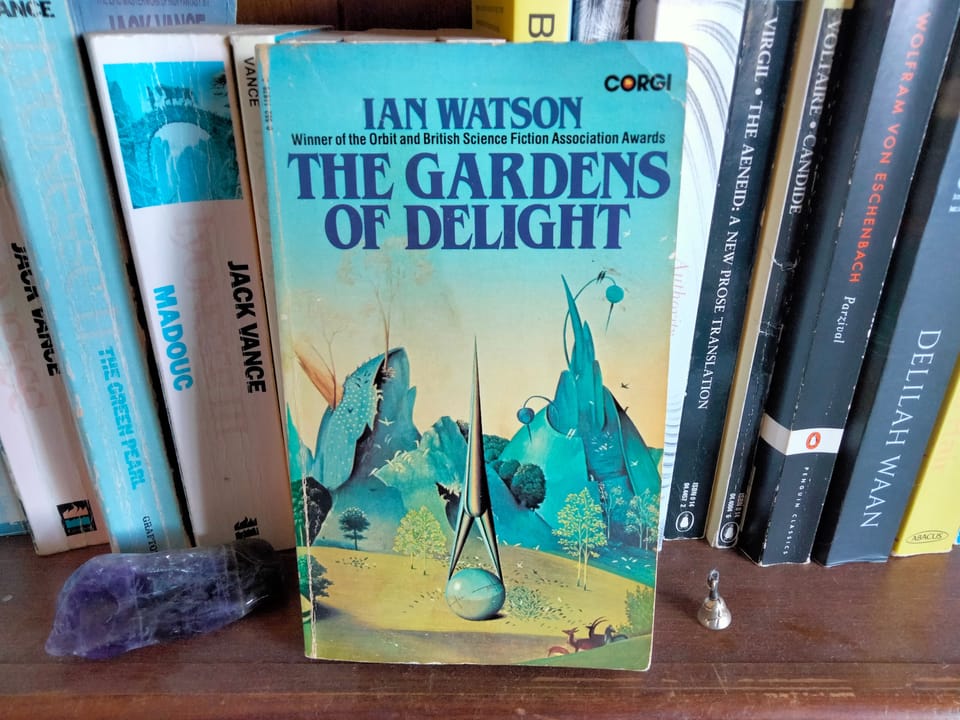

Paradise and Hell: “The Gardens of Delight” by Ian Watson

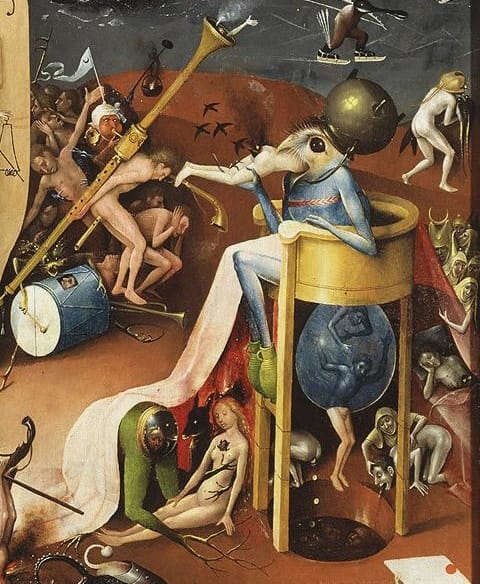

My third foray into the works of Ian Watson, after Queenmagic, Kingmagic and Deathhunter. This was my favourite so far. Like the other two, it begins from an absolutely barmy high-concept premise. In this case: a spaceship full of explorers arrive on an uncharted planet, only to discover it looks exactly like Hieronymous Bosch’s famous painting The Garden of Earthly Delights. And I mean exactly like, down to the individual characters and set-pieces that appear in the original.

“How can this be?” is the basic hook of the novel. The protagonists are a team of doctors and scientists, and much of the entertainment comes from seeing this group of rationalists struggle to make sense of a world that runs on mystical symbolism rather than material principles.

Just like Bosch’s painting, the planet is divided into three sections: the Garden of Eden, the Garden of Earthly Delights, and Hell. When humans die in one area they are reincarnated in another, according to their level of spiritual development.

Ian Watson seems to be fascinated with the idea of constructed worlds, whether it’s the Chess- and Monopoly-based settings of Queenmagic, or the post-death ecosystem in Deathhunter. Here, the world has been designed by God himself—or at least that’s what the denizens of the Gardens believe. The entire planet is a kind of spiritual distillation chamber, designed to teach mystical lessons and help each soul get (literally) closer to God.

The book is full of half-baked theories drawn from philosophy, theology and psychoanalysis. Alchemy and the Philosopher’s Stone come up frequently, as do Jungian archetypes. At one point, the primary protagonist relives his “conception trauma” by climbing up the inside of a giant stone penis, symbolically replaying the role of the sperm when he emerges from the summit.

I have to confess that I love this stuff; it appeals to my inner stoned teenager. A sample of the more mind-expanding quotes includes:

- “the left side of the brain has been waging a propaganda war against the right hemisphere ever since the left side invented language”

- “Hell and the Gardens have the shape of a Klein bottle in the God's mind”

- “Equip yourself with all the traumas you haven't got, because it's an illusion that you haven't got them”

- "The Devil is the legalistic, analysing side of God, alienated from Him because the whole God is paradox"

Along with these dubious insights come a range of theological puns, e.g.: “God only knows why we're here.” “That's right, he does.” Or: “Go to the devil!” “Oh, I will.” etc.

Probably the dumbest idea Watson introduces is a connection between spiritual development and skin colour. Yes, really. Anyone familiar with alchemy will remember that the process to create the Philosopher’s Stone is divided into four colour-coded stages, beginning with nigredo (black). In the symbol-logic world of the novel, this means that black people literally get a head start on the journey to enlightenment. What's more, the white characters have to be reincarnated in black-skinned bodies as part of their progress.

This might have been an interesting idea, if it was handled with great subtlety and care. Ian Watson is definitely not that writer. He just hasn't done the work necessary to write about black people, instead falling back on lazy cliches. The future Earth society is meant to be a colourblind one, and the black scientist Muthoni Muthiga is treated as equal to her white colleagues. But she’s also described as coming from “Africa” (no particular country), randomly blurts out phrases in Swahili, and is repeatedly referred to in the narration as a “negress”. It's a big bucket of yikes. The only saving grace is that Watson simply forgets about the whole skin colour plotline halfway through the book.

The highlight of the book is, naturally, the sequence that takes place in Hell. I’ve written before about how much I love books that go to Hell. Watson's depiction doesn't have the raw force of Michael Shea's Nifft the Lean or Christopher Buehlman’s Between Two Fires, but it's still plenty entertaining. Among the more inventive tortures are a musician crucified on his own violin, and a character boiled alive inside a giant gingerbread man mould. Also, the only way to leave Hell is to convince Satan to eat you and then shit you out into the Garden of Eden.

Even after the characters meet God himself, there is more psychedelic nonsense to enjoy. The craziness doesn’t quite rise to the level of, say, Philip K. Dick or Alfred Bester, but it at least makes a good stab in that direction. The answer to the novel's driving question, e.g. “Why the fuck is this planet like this?” is not terribly original, but it’s satisfying enough.

Watson's prose is always competent, and occasionally inspired. The best scenes have a chaotic, almost slapstick energy that captures the vibe of Bosch’s painting. For instance, this scene showing the aftermath of the spaceship’s landing in the first chapter:

In the large meadow beyond, a few casualties lay about on the turf. Mainly they were giant fish. A smell of charring wafted from them. Slow creatures! A wonder that they could move overland at all. But this was how they evolved, straining upwards towards the condition of legs, or even wings. People often took pity on them and carried them. As indeed some human refugees from the meadow were doing now, bearing a great red mullet between them. They laid it down on the turf so that it could see the amazing silver tower. The mullet’s eyes gaped glassily up at it, observing what was towering up into the air as foggily and as out of focus as people see things underwater…

Above, over black burnt earth, rose the sleek metal tower. The landing jacks had ruptured through the turf down to bedrock, as though the world was a mere skin and a thin skin at that. Assessing the excellent uprightness of the tower—which the mullet must surely envy—a man and a woman who had been carrying the fish proceeded to perform a perfect handstand, face to face, and in that precarious position, upside-down, they made sweet love.

Many scenes from the original painting appear directly in the book. These range from large set-pieces, like the petrified giant with a bar inside his stomach, to small details, like the woman emerging from an oyster shell. Watson lovingly recreates each of these images in prose form. The obsessive passion that comes through in these descriptions is completely charming. You can tell that Watson loves this painting and has spent a lot of time looking at it. I love to see an author who is unapologetically On Their Bullshit. It’s something that seems much less common in the SF genre today.

I've been thinking (again) about what I love about classic sci-fi and fantasy that's missing from modern novels. And the word I keep coming back to is modesty. I think The Gardens of Delight is a modest book, despite its grandiose speculations on the nature of God and humanity. It doesn't claim to be anything more than what it is: a carrier bag full of the author’s quirks and obsessions. Like many classic SF novels it is short (185 pages) and gets straight to the point. It does not try to convince you that reading this book will purify your soul or help reorganise society. It just exists for itself.

In the current SF market, modesty is a disadvantage. Every novel must claim to serve some deeper moral purpose—tearing down the patriarchy, or affirming the strength of found family, or rebuilding our broken relationship to the natural world. But it seems to me that this drive toward making every book into “essential reading” actually suffocates what makes fiction truly valuable. It flattens and homogenises the unique voice of each writer, their strange tics and fixations. Conversely, a book written with modesty and humility will be free to become fully, weirdly itself.

Availability: The Gardens of Delight has been reprinted in the Gateway SF Classics range, so it is available as an ebook. Old paperback copies are also not hard to find.

Header image: art by Peter Goodfellow

Member discussion