The Psychedelic Wizardry of Roger Zelazny’s "The Changing Land"

Digging through the shelves of second-hand bookstores is one of the bibliophile’s great pleasures. I could tell you it’s about the smell, the aura of history, the ghosts of many hands that have touched the books before you. And it is, but it’s also basically an endless gacha game: the hook is that you never know what you’re going to get. Sometimes there’s nothing but crap. Other times you stumble upon a rare classic you’ve wanted for years and it’s priced $2.99. And still other times you pick up a book you’ve never heard of and know instantly you have to have it.

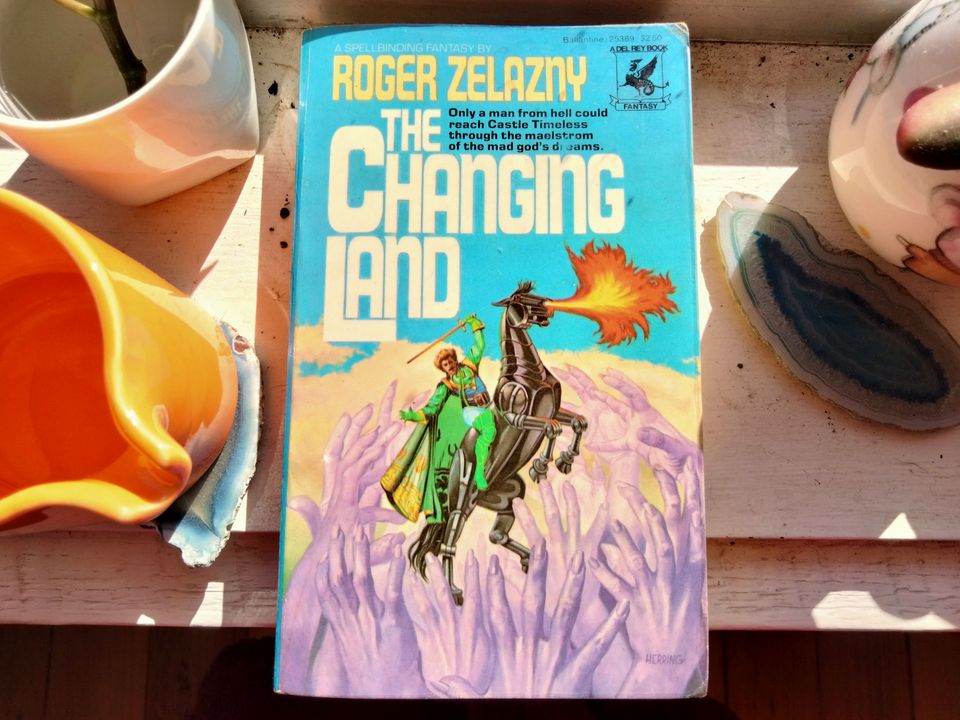

Roger Zelazny’s The Changing Land (1981) was such a book for me. Back then I was not familiar with his more beloved works like Amber and A Night in the Lonesome October, so the book sold itself on the strength of its cover alone. Along with outrageously good artwork by Michael Herring, the cover bears one of the all-time greatest taglines: “Only a man from hell could reach Castle Timeless through the maelstrom of the mad god’s dreams.” How could anyone put that back on the shelf?

(Although: the line is technically incorrect. Several other characters do, in fact, reach Castle Timeless through the maelstrom of the mad god’s dreams.)

The Changing Land delivers 100% on the promise of its cover. It is a cracking good pulp fantasy novel, bursting full of demons, alien gods, and the kind of wizards you could see spraypainted on the side of a van.

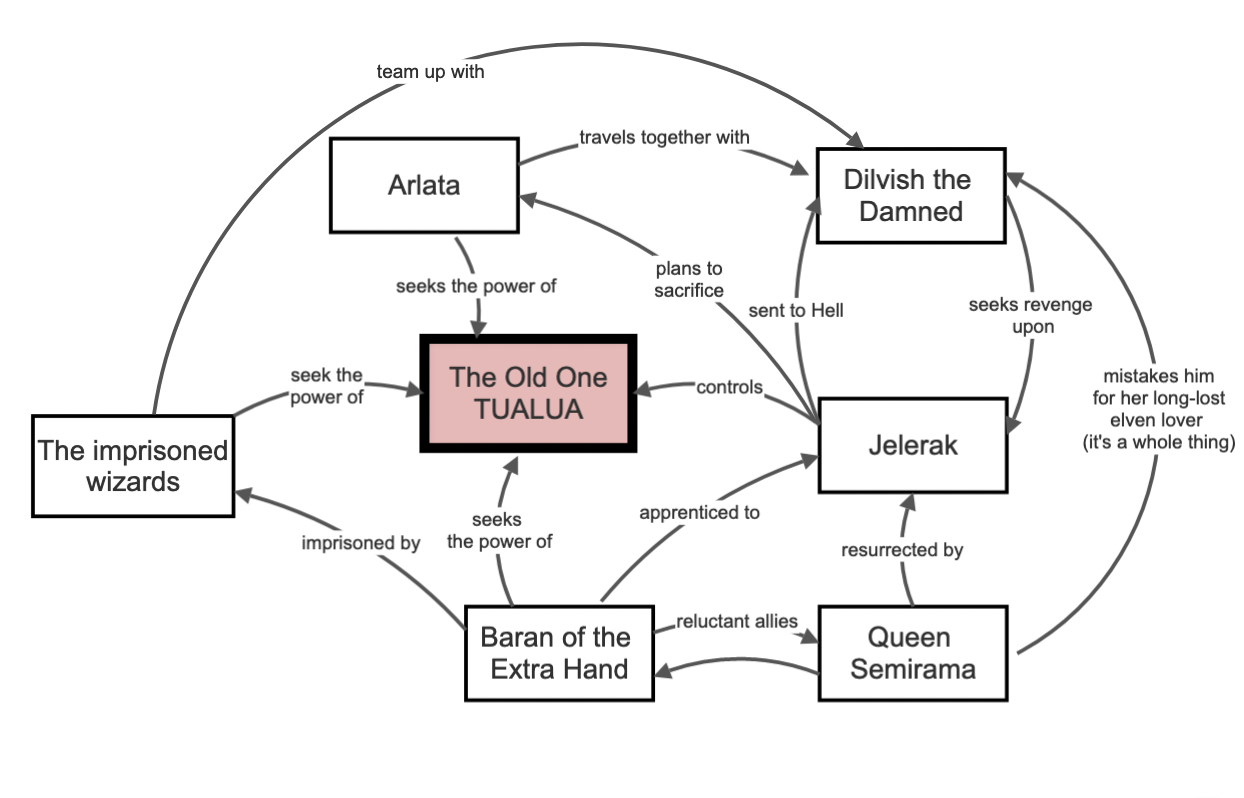

The story revolves around the aforementioned Castle Timeless, in which the mad god Tualua is sealed but slowly breaking free. Tualua’s dreams blast the surrounding landscape with waves of metamorphic magical madness, creating the titular changing land. Our hero, Dilvish the Damned, is trying to cross this land to take revenge on the castle’s owner. Various other wizards inside and outside are scheming to seize Tualua’s power for themselves. Trying to explain all plot’s twists and turns would be a fool’s errand, so instead I’ve drawn up this chart to give an impression of how much is going on (in under 250 pages, no less):

It may look like a mess, but it all makes perfect sense with Zelazny’s steady hand upon the tiller. But the true excellence of The Changing Land is not in its structure but its texture; in the constant stream of elemental images that decorate the pages like weird little jewels. From the third chapter:

Leaping among large, cube-shaped green rocks in a very unhorselike fashion, Black bore steadily to the right… He leaped a hedge of flames which sprang up before them, and for a time raced parallel to the course of a black and boiling river, down through a canyon where screams too high-pitched to be human filled the air. Along the river's bank, black flowers swayed, hissing and spitting. Tiny points of light rose above the dark waters and drifted off, to explode with soft popping noises, emitting noxious odors amid showers of sparks. The ground continued to shake and the dark waters overleaped their banks in places, staining the rocks and the land about with tarlike films. A winged, monkey faced thing the size of a large bird flew at them, shrieking, talons outstretched.

The book is full of this stuff. Elemental forces (fire, ice, acid, scorpions) are splattered across the pages like spills of technicolor ink. Demons scuttle down corridors, skeletons ride through the sky. One character is accompanied everywhere by an entourage of bats, spiders and dancing rats. And then there are these guys:

So quickly that she was almost uncertain as to what had occurred, a horde of snouted, piglike creatures of considerable size, running on their hind legs, tore past with snuffling, panting noises. Some of them appeared to be carrying cushions and earthenware jugs. As they vanished in the distance, it seemed almost as if they had begun chanting.

"The little bastards are out in force," Baran remarked. "A few of them always manage to make it upstairs and disturb me when I'm in the library."

These pig-people, along with various other critters, don’t play any role in the main story. Zelazny seems to have included them out of sheer exuberance. And indeed there are times when these chaotic images threaten to overwhelm and obscure the plot like a rising tide. The page becomes crowded, recalling the hellscapes of Hieronymous Bosch or the frenzied psychedelia of Pendleton Ward’s The Midnight Gospel.

But all this chaos is balanced by some lighter moments of farce and confusion. Characters pursue cunning schemes based on incorrect information; lies and misapprehensions collide in unexpected ways. There is a running joke about immortal characters being unable to tell the difference between grandparents and their grandchildren.

There are quieter moments, too, in the scenes outside the changing land, where a guild of bureaucratic wizards tries to figure out what is going on without sticking their necks out too far. These guys (and they are all guys) are a lot of fun, acting less like masters of cosmic power than mid-century office managers, fumbling with records and kvetching about their ineffectual superiors. They contact each other using crystals that work exactly like telephones; one character actually says “let me take this on my other crystal”. Their wizarding guild used to be called “The Brotherhood” but changed recently to “The Society” under pressure from female spellcasters.

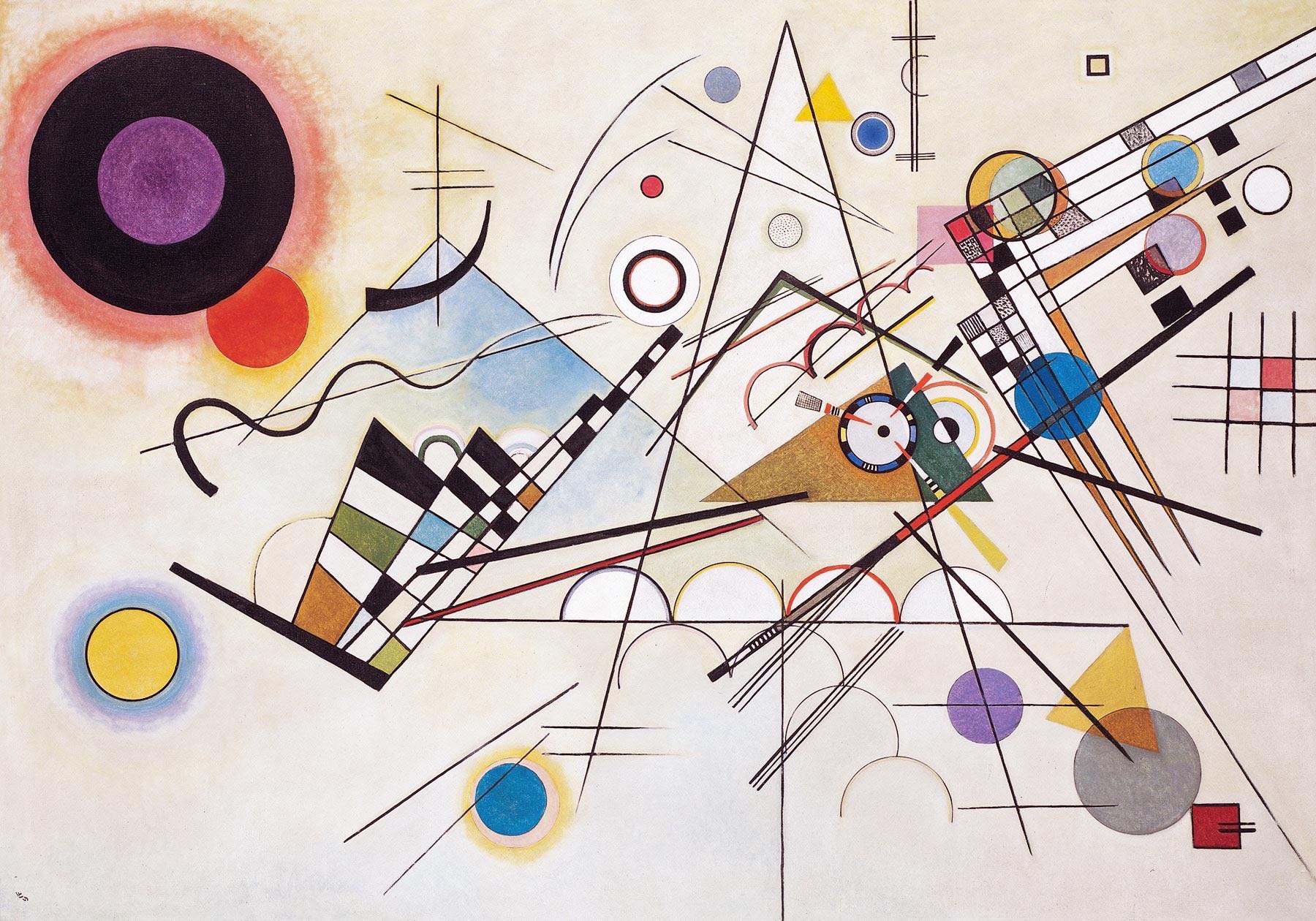

A particularly good scene has one of these Society mages, Holrun, trying to enter the castle through its network of teleporting mirrors. To infiltrate the mirror-spell he travels to the “plane of structures”—a sort of Platonic realm where the raw work of magic takes place. Here, spells and casters are rendered as abstract geometric shapes. If much of this novel reads like a Bosch painting, then this scene is a Kandinsky:

He saw the spell and shifted to the plane of structures, where he felt more comfortable. It became a series of interconnected lines of various colors, all of them pulsing, beads of energy passing in seeming-random fashion from junction to junction.

The abstract structure is guarded by a “fuzzy blue coil” and another intruder manifests as “an inquiring hook, pulsing redly”. After allowing these two to duke it out, Holrun enters and takes control of the mirror-spell, in a sequence is uncannily reminiscent of a computer hacking scene from the as-yet-unborn genre of cyberpunk:

He advanced upon the lower angle. The only thing remaining to be determined was the direction in which the spell flowed. He had two choices. The wrong one would undo it, totally deactivating the mirror as he ran through it backward.

One line was thinner than the other, indicating a high pitch to the sorcerer's voice as he had uttered that sound. Normally, a spell commenced on a lower note than it ended, though this was not always the case. Either line, for that matter, could also represent a preliminary gesture.

[…]

He rushed forward and penetrated the end of the thinner line. The striking of the cold blue thing was beyond his perception, for he was already moving within the system of the spell by the time it arrived.

He realized that he had guessed correctly as he heard the first word—a fairly standard opening ringing all about him. He advanced through the spell, receiving impressions of each gesture, living within each word, burning them all into his memory... he spun off from his special element, creating a simple subspell system, all of whose lines paralleled and were superimposed upon existing spell-elements.

After more wizardly machinations, the novel reaches its climax, again with an element of farce. A gang of sorcerers, trying to harness the Old One’s power, perform an ill-advised ritual that causes Castle Timeless (the hint was in the name) to become unstuck in time. The castle accelerates through the centuries, racing toward the final collapse of the universe. But fortunately for everyone involved, it turns out that time is circular, and passing through the end brings you back to the beginning. At the dawn of time we encounter the Elder Gods literally playing dice with the universe:

Dilvish followed the ruddy arm with his eyes up into the misty area, where, after several moments' staring, he was able to discern the outline of a colossal kneeling body, vaguely human in form, stars shining through it, meteors in its hair. It raised the arm an unimaginable distance into the sky, fist shaking. It was only then that the cube-like shape of the rocks registered itself upon Dilvish's understanding.

He looked away. His eyes, now accommodated to the scale of things and the wavelengths involved, had less difficulty in discerning other monolithic beings—like the great black figure, head propped on one hand, two arms folded across its breast, the fingers of a fourth hand stroking the south eastern mountaintops above which it reclined; the shadowy white figure with one eye and one gaping socket, which leaned upon a staff that reached higher than the sun, stars like fireflies caught in its floppy hat; the slow-dancing woman with many breasts; the jackal-headed one; the whirling tower of fire…

Here Zelazny is riffing on Lord Dunsany’s Gods of Pegāna—compare the above passage to this from Dunsany. There are other playful intertextual links as well. The wizards are equipped with Boots of Elvenkindand Dust of Appearance,straight out of Dungeons & Dragons. And when the heroes return to the present after their encounter with the gods, they are menaced by the time-travelling Hounds of Tindalos, originally of Frank Belknap Long.

In this, Zelazny is of course following a long tradition of SFF writers playing with each others’ toys. H. P. Lovecraft used to name-drop deities from Robert E. Howard’s Conan stories, and vice versa. Fritz Leiber and Joanna Russ together invented a fling between their sword & sorcery heroes, Fafhrd and Alyx respectively. Other examples abound. As a result, many of these novels feel as though they exist within—not quite a “shared universe”, but more like a common aesthetic field.

And this sense of play is really at the heart of what makes The Changing Land such a pleasure to read. It is hardly a great work of fiction. It’s messy in parts, sometimes technically sloppy, and lacking in higher ambition. And yet it has a certain quality, a sense of self-assurance, that makes it incredibly charming. This quality—which might also be called integrity or exuberance or just plain weirdness—is perhaps what I prize most in fiction. I love books that exist first and foremost for themselves; books where the reader is a welcome guest, but not a necessity. If you decline the invitation, the party will carry on between the closed covers. Those are the kinds of books that Paperback Picnic is all about.

Member discussion