The First Secondary World

Where is Westeros in relation to Earth? It’s nowhere. The question doesn’t make sense. You can’t get to there from here. It’s a secondary world.

This concept—a fictional setting that lacks any continuity with our own—is so commonplace today that even someone with no interest in sci-fi or fantasy would probably grasp it intuitively. But when we look back on the history of fiction, it’s startling to realise just how recent this idea is. I suspect that as little as 100 years ago, most people would have had a very hard time wrapping their heads around it.

Humans have always told stories set in fictional locations. Back as far as the Odyssey and the Epic of Gilgamesh we have characters visiting mythical forests, imaginary islands and so on. But all these places are still grounded in the real world. The total disjunction between reality and fantasy—what I’ll call an independent secondary world—was not invented until the mid-19thcentury, and was not in common use until the 1950s. Indeed, it seems like the development of the modern Western mind with all its influences (capitalism, individualism, atheism) was a prerequisite for us to even conceive of fictional worlds in this way.

Let me define my terms carefully here. It’s common for both fans and scholars to talk about settings like Narnia, Hogwarts or the Land of Oz as “secondary worlds”. But these are all what I’ll call “additive” secondary worlds, because they present themselves as existing in addition to the real world.

There are numerous ways that a world can be “additive”. It might be placed in our world’s distant past or far future; it might be in outer space, under the ground, or hidden in plain sight. It might be accessible through a portal or a dimension-hopping device, or it might be an alternate timeline that diverges from our own. The common thread in all these cases is the connection to baseline reality.

The independent world has no such connection. Where the additive world says “yes, and” to reality, the independent world says “no, but”.

The line between these categories can sometimes be razor-thin. Consider the Star Wars films, which each begin with that beloved phrase, “A long time ago in a galaxy far, far away…” This line situates the films, however tenuously, within the bounds of our own universe. If we were to cut those few frames from the start of each film, the connection would be severed.

This example also illustrates another important principle: for a setting to be additive, its connection to the real world must be stated explicitly or implicitly within the text. We cannot simply assume. Of course there is nothing to stop someone from speculating (presumably through a cloud of bong smoke) that A Song of Ice and Fire actually takes place on a planet in the vicinity of the Andromeda Galaxy, and therefore we are all technically living in the same universe as Jon Snow. But the textual evidence is not there.

Why am I going to such lengths to make this distinction? Is this just a pedantic fanfic exercise, like the theory claiming that dozens of interconnected TV series all take place in the imagination of a single autistic child? Well… maybe that’s part of it. But these categories also have significance for the history of fiction, and the genesis of the fantasy genre in particular.

I originally set out to write this post as a search for the very first independent secondary world. It turns out someone has already done this. Matthew David Surridge, writing for Black Gate in 2010, exhaustively surveys the possible candidates, and concludes with a convincing argument that the answer is Phantasmion (1837) by Sara Coleridge.

Although Phantasmion is written in the style of a children’s fairy-tale, it also has several elements we would associate with modern worldbuilding. There is a fictional geography with named landmarks (“The river Mediana”, “the kingdom of Almaterra”) and a history that involves different kings, queens and nations. There is even an early attempt at economic materialism: two kings go to war over control of a region “rich in metals and other stones”. Just as importantly, there are no references to real-world locations or events. By the definitions I laid out above, thisis clearly an independent secondary world.

But Phantasmion is a weird outlier. If we were to remove it from consideration, then the next possible “runners-up” would be works by William Morris or Lord Dunsany, written nearly 60 years later. The very fact that Coleridge was so far ahead of her time means, paradoxically, that her work doesn’t tell us much about broader historical trends.

Instead of asking who did it first, then, I want to look at when and how this idea became commonplace. And to do that, we need to start at the very beginning.

The earliest “fantasy worlds” are found in mythological or religious literature, which don’t conform neatly to modern categories of fact and fiction. Regardless, these sacred stories are necessarily located in the real world. No Indigenous people have passed down oral traditions about a made-up world wholly disconnected from their own; the very idea is nonsensical.

Perhaps the first piece of fantastic literature that presents self-consciously as fiction is Lucian of Samosata’s A True Story (2ndcentury AD). In this comic travelogue, Lucian claims to have been aboard a ship that was sucked into outer space, where he became embroiled in a war between the native peoples of the sun and moon. All this is Lucian’s way of parodying the unlikely claims of other travel narratives circulating at the time.

Lucian’s piece sets the template for secondary-world stories for the next seventeen centuries or so. It begins in the ordinary world, travels to the “otherworld”, and then returns to reality. This same basic pattern is repeated in stories as diverse as the travels of Sindbad the Sailor in the Arabian Nights, the quest of Tripitaka in Journey to the West, and the voyages to Tir na nÓg depicted in various Celtic tales.

All these otherworlds are situated at the margins of the known. As the colonial era expanded the borders of the known world, the locations of fantasy likewise fled outwards. For medieval readers, the kingdom of Prester John was believed to exist somewhere in India. But by the 18thcentury, the frontier had been pushed out to the New World; thus in Candide (1759), Voltaire describes a fictional paradise in the land of El Dorado, somewhere deep in the jungles of South America. A little later, the young Brontë sisters would write stories about Glass Town, a fictional colony somewhere in Sub-Saharan Africa, which was the frontier of their own time.

What this outward movement tells us is that even writers of the fantastic wanted their stories to have some level of plausibility. All these places didn’t exist, but they could have.

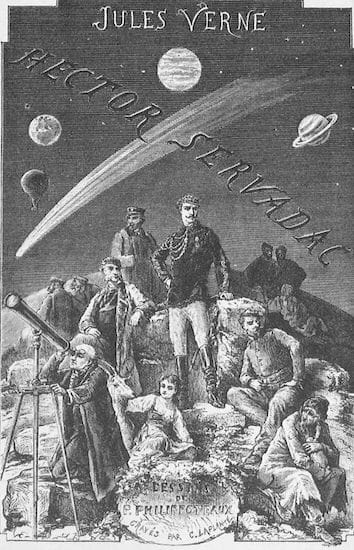

By the 19thcentury, the borders had moved again. The world was mostly mapped. There was nowhere left to put a fantasy kingdom full of blemmyae or cynocephali. So, like toothpaste squeezed from a tube, the imaginary worlds burst outward into new realms. Space fiction began to emerge with novels like Jules Verne’s From the Earth to the Moon (1865) and Percy Greg’s Across the Zodiac (1880). Other worlds burrowed underground, creating the Hollow Earth subgenre.

It was also at this time that the first future stories appeared. This topic could easily be a whole essay in itself. Suffice to say that, outside of a few dramatic outliers such as Samuel Madden’s Memoirs of the Twentieth Century (1733), stories set in the future were virtually unknown until the mid-1800s.

What’s striking about all these new forms of fantasy is that they still begin and end with a frame narrative that fixes them to the real world. The narrator is usually an explorer, who finds a way to travel into space, or falls down a hole into a subterranean world. In stories about the future, the protagonist nearly always begins in the present day and then travels through time. The most famous mechanism for this is, of course, H. G. Wells’ The Time Machine (1895), from which has grown an entire subgenre of science fiction. Another means of accessing the future is found in Mary Shelley’s The Last Man (1826), in which Shelley claims that her work is really a translation of secret prophecies she found in a cave near Naples.

Use of the frame narrative slowly withered away during the first few decades of the 20th century. An amusing example of its demise comes in E. R. Eddison’s The Worm Ourobouros (1922). This high fantasy novel begins with Lessingham, a native of Earth, who is carried in a magical chariot to the planet Mercury to witness the deeds of great heroes there. After passively observing the main characters, Lessingham eventually fades out of the story and is never mentioned again. The frame narrative literally vanishes, not on the timescale of literary trends, but in the course of a single book!

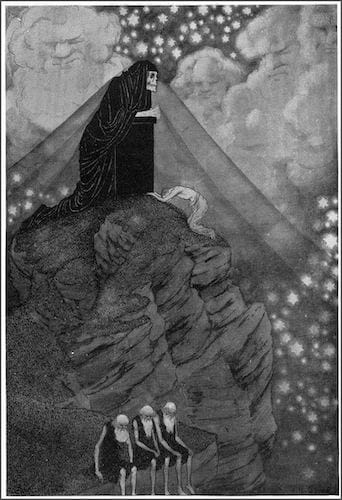

Another milestone on the road to modern fantasy is Lord Dunsany’s The Gods of Pegāna (1905). This collection of short fables presents itself as a wholly original mythic cosmology, beginning from the premise that all existence takes place in the dreams of the ultimate deity MANA-YOOD-SUSHAI (name always capitalised).

Dunsany was evidently inspired by collections of Asian and Middle Eastern folklore, but his own stories are not retellings, nor are they clearly tied to any geographical region.

Much like The Worm Ourobouros, The Gods of Pegāna retains a slight but definite connection to the real world. Dunsany places the stories in Earth’s distant past with the opening line: “Before there stood gods upon Olympus, or ever Allah was Allah…” Later in the book, the prophet Imbaun has a vision of the future in which humans will “yoke… beasts of iron” and “men [will] slay men with mists” (e.g. gas weapons, which were a new technology at the time Dunsany was writing).

So Dunsany didn’t quite conceive Pegāna as a wholly separate world. But he was the first writer who constructed an entire mythological system for fun. Humans have been conceiving of gods since long before we could write them down, but until Dunsany, we always conceived of them as being real.

This brings us to the two great heavyweights of mid-century fantasy fiction: The Chronicles of Narnia (1950-56) and The Lord of the Rings (1954-55). At this point, the connection to the real world is mostly vestigial. Even avowed Tolkien fans might not recall that Middle-Earth is technically meant to be the distant past of Earth. The connection is laid out in the prologue to The Fellowship of the Ring, with an invented bibliography explaining how Frodo’s narrative (“The Red Book of Westmarch”) was passed down through history to the present day.

Meanwhile, C. S. Lewis was drawing away from reality in a direction. The world of Narnia really is a separate universe, but still connected because you can get to it through a magic wardrobe (or perhaps more importantly, because Jesus Christ appears in both worlds in different guises).

It’s as though the secondary world sits at the end of a long string of blown glass, dangling far from the reader-world, still connected, but ready to snap off altogether.

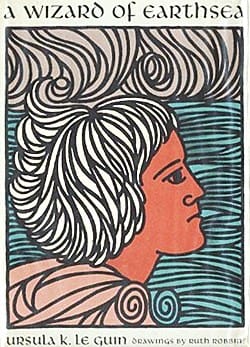

Over the next few decades, independent secondary worlds became ubiquitous in fantasy fiction. The first to achieve broad success was probably Ursula Le Guin’s Earthsea novels, beginning in 1968. Ten years later, tabletop gaming began to entrench the concept into fan culture with settings like Greyhawk, the Forgotten Realms and the world of Warhammer. By the time nerd culture was rebranded as pop culture in the mid-2000s, there was nothing at all remarkable about the idea of a fictional world separate from our own.

What I’ve tried to show with the above history is that this idea didn’t emerge fully-formed from any one author’s mind. It grew in a series of steps over many decades. When Le Guin conceived of Earthsea as entirely disconnected from Earth, it’s not clear that she even considered this as a major innovation. We know she was influenced by Dunsany, Eddison and Tolkien, all of whom treated their frame narratives as mere afterthoughts. She may have discarded that frame without thinking too much about it.

Lastly, I want to ask: if this idea has emerged so recently, why now? Why here and not elsewhere?

If you’ll forgive me some rather broad cultural speculation, I think it can be traced back to the Protestant Reformation. More specifically, it can be seen as a development from the splintering of worldviews between different Christian denominations—a process that historians call “confessionalisation”.

The word “confession” in this context doesn’t refer to an admission of guilt, but a statement of faith. It’s a document that lays out the specific beliefs of a religious community. Often, members of the community would read this document out loud, confirming their place in the group and distinguishing themselves from other denominations with different beliefs.

As Diarmaid MacCulloch puts it in his History of Christianity (2009):

As a result of this north-south divide [between Protestants and Catholics], people were forced to make decisions, or at least their rulers forced decisions on them. Which checklist of doctrine should they sign up to?

Historians have given an unlovely but perhaps necessary label to this process: confessionalisation—creating fixed identities and systems of belief for separate Churches which had previously been more fluid in their self-understanding, and which had not even sought separate identities for themselves… In western Europe it was difficult to escape this impulse to tidy and to build boundaries.

Before the Reformation, “confessions” of this kind were generally not a major feature of Christian life. People from different regions certainly had differences in belief and practice, but they didn’t see these differences as setting them apart from one another. Everyone was part of the Catholic Church; some Catholics just did things differently to others.

The emergence of a multitude of Protestant churches, each with their own detailed opinions on the Bible and the faith, led to what MacCulloch calls a “competitive religious market”. For the first time in Christian history, people had a choice about what to believe. Often enough this choice was made by kings and princes who then enforced their creed with violence. But there were areas of religious tolerance—in the Netherlands, Transylvania, and eventually England—where ordinary people really could “shop around” in a marketplace of religious ideas. This freedom, combined with the emerging culture of market capitalism, allowed people to see their faith as something chosen by an individual rather than handed down by their parents or their king.

This is where it comes back to fantasy novels. When you make a statement of faith, you aren’t just saying what you believe about God, the Church, or right and wrong; you’re also saying what you believe about the shape of the world. You’re doing worldbuilding.

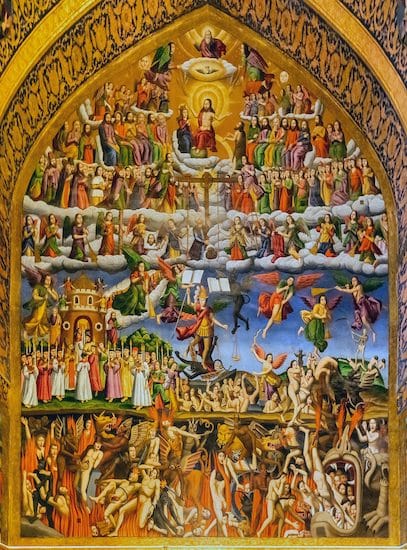

If this seems like a stretch, remember that one of the biggest disagreements Martin Luther had with the Catholic Church was that he denied the existence of Purgatory: an entire sub-world, one quarter of the overall Catholic cosmology. For Luther, Purgatory was not lore accurate, and he did not accept it into his headcanon.

So now we have not just a “marketplace of ideas” but a “marketplace of cosmologies”. You could choose which version of the universe you believed in. Over time, the logic of the market turned these universes into commodities, things that could be owned by an individual. We can see that process reflected in the way that religious beliefs became more and more personalised over the following centuries. Perhaps the purest expression of this trend was William Blake, who created a personal mythology that was part imagination, part vision, populated with its own deities. But there were many other visionary “worldbuilders” in this era, from Emanuel Swedenborg (who wrote detailed descriptions of his journeys through Heaven and Hell) to Helena Blavatsky (who described a spiritual prehistory of the Earth and the fall of Atlantis).

All of this leads back again to Dunsany’s Gods of Pegāna at the beginning of the 20thcentury. Among this “marketplace” of personal mythologies, it was not so great a stretch for Dunsany to try inventing one of his own, and finally discarded the sacred aspect of the story altogether.

It’s interesting that Tolkien, the writer who did the most to popularise “worldbuilding” in the mainstream consciousness, wished to take it back to its religious roots. He considered the creation of new worlds to be a sacred task. “It may be a far-off gleam or echo of evangelium in the real world,” he writes in “On Fairy-Stories” (1939).

In Tolkien’s view, the work of the fantasy writer imitates God, and therefore glorifies Him. But for modern fantasy writers, God is most often removed from the equation altogether. There is only the human author, wielding absolute power over their fictional domain.

Today, independent secondary worlds are a disposable commodity. Whole universes are invented for a single novel, a single short story. Fans grow their own mini-worlds in form of alternate-universe fanfics. Dungeon Masters sketch out pantheons on scrap paper a few hours before their game night is due to begin.

None of this is to say we should go back to a time when there was only one world. But it’s worth remembering how fresh this all is; how, almost within living memory, the ordinary entertainments of today were something new and strange.

To leave a comment or suggest a weird old book, find me on Bluesky @gnipahellir.bsky.social, or email me at paperbackpicnic@gmail.com. I am no longer on Twitter.

Member discussion