Two Books by Surrealist Women

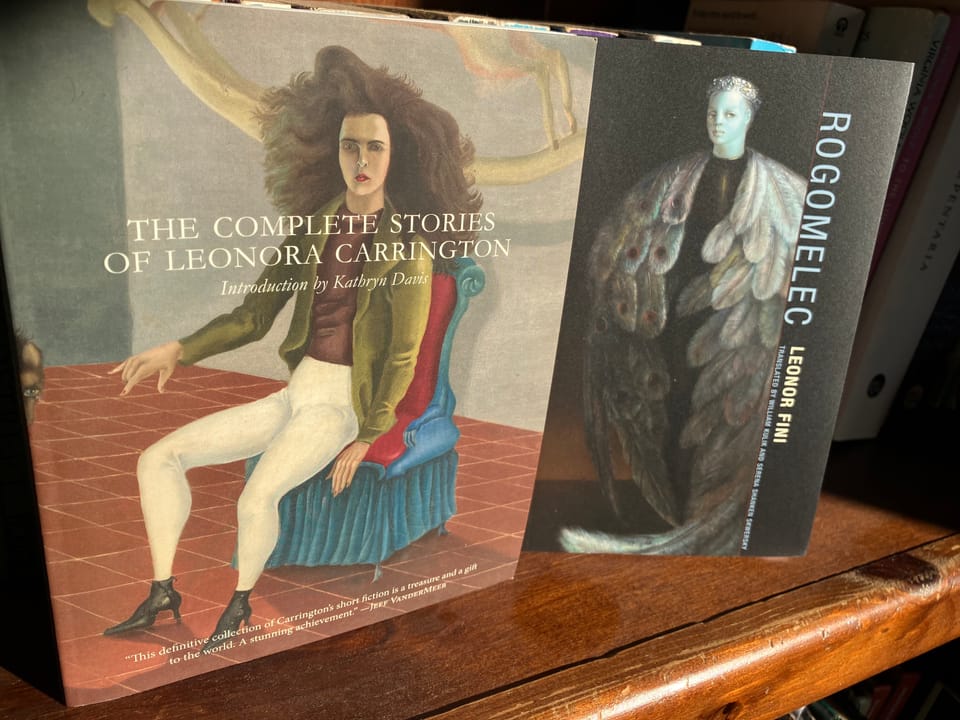

My favourite bookshop in the world is Metropolis Bookshop in Melbourne CBD. It’s an incredibly cool place where I can always be assured of finding something new, mysterious and strange on the shelf. My most recent purchases there have been two books of fiction by Surrealist painters: the novella Rogomelec by Leonor Fini, and The Complete Short Stories by Leonora Carrington. Technically these are a little outside the normal scope of this blog; they’re not genre fantasy, but they are certainly fantastical, and they both gave me a similar feeling of freedom and joy that I get from authors like Samuel R. Delany or Brian Aldiss.

I hardly knew anything about Fini or Carrington before I picked up these books. In this I’m probably the opposite of most readers, since both women are better known for their paintings than their writing. Both were associated with the Surrealist movement in the 1930s and 40s. They were close friends, although in true Surrealist style they also had a grand falling out, with Fini destroying her half-finished portrait of Carrington in a fit of rage.

Fini has been described as the “darker sister” of Carrington. Her paintings are more restrained and ethereal, whereas Carrington’s are grotesque and bombastic. The same division is clear in their fiction. Rogomelec is a gentle yet uncanny tale about an unnamed narrator looking for healing in a secluded monastery. Carrington’s stories by contrast are overflowing with violence and energy. Several of her stories also include churches and monasteries, but she delights in depicting these holy spaces desecrated by wild animals and rebellious women.

Both writers share a disregard for conventional narrative structure. It’s probably a cliche to even bring this up, but their stories feel like paintings. The prose is rich with imagery, each sentence like a brushstroke across the page. But the stories are also shaped like paintings. Instead of a beginning, middle and end, they are structured around figures, foreground and background.

This structure is really clear in Rogomelec. This novella concentrates its most powerful imagery in the middle of the text, just like a portrait places its subject in the centre of the frame. The first section follows the narrator’s arrival at the monastery. It is gently paced and written with spare, retiring prose. Then, in the physical centre of the book, the story builds to a theatrical climax. Dozens of masked monks march across the page. The narrator is dressed for the occasion in an outfit made from live octopuses: “multicolored and phosphorescent… Prussian blue, orange, cobalt violet.”

Next comes:

…an advancing parade of furry creatures with enormous eyes, and one-eyed creatures with huge, long black eyelashes in perpetual motion; others wore large jackets made of strings of shells and trains of algae… huge wigs inhabited by birds coming and going, beards from which the little snouts of rats would poke out. Other small animals made up in liquid gold could be seen scrambling about to where the light was. One of the monks bore hair made of vipers.

There are more outbursts of surreal imagery, including fireworks and flares, “bestial cries and solemn songs”, a gender-bending monk in doll makeup, and others in religious ecstasy “show[ing] their bare buttocks on which blazing suns were painted”.

The final section returns to a calmer tone. The narrator wanders through overgrown ruins beyond the monastery, uncovering faded artworks and forgotten rooms. Here the text is quiet and restful once more, capturing the special stillness of being alone in places of great antiquity.

This pyramid-shaped narrative, with the climax in the middle, is all “wrong” by the standards normally applied to short fiction. We expect stories to peak near the end, with a brief denouement afterwards. But it makes sense if we see the monks’ parade as the “figure” in the centre of a painting, with the first and last sections corresponding to the blurry, less-detailed areas near the edge of the frame.

Leonora Carrington’s short stories are even more chaotic, in both structure and content. Most of them are very short and rush from one image to the next at a breakneck pace. They are full of animals, sex, filth and violence. Humans turn into beasts, food comes to life, and metaphors become literally real. Certain eerie motifs recur throughout, such as cannibalism, hyenas, and a mysterious substance called “cosmic yarn”.

Many of the stories end very abruptly, often at a moment of climax or revelation. In some ways this mimics the way dreams end suddenly upon waking. But I also like to imagine that Carrington, in the midst of a wild and sensual life, simply set down her pen as soon as she got bored.

As the name implies, The Complete Stories is comprehensive, including pieces ranging from the 1930s to the 1970s. Among the highlights are:

- “The Debutante”: the first and perhaps most conventional story in the collection. It follows the classic formula of two characters trading places, except that one of these characters is a teenage girl and the other is a ravenous hyena.

- “As They Rode Along the Edge”: a bloody fairy tale about a wild woman seeking revenge for the murder of her lover, an enormous boar. There is a truly jaw-dropping moment when, shortly after the boar’s death, the heroine gives birth to “seven little boars” and immediately cooks them “as a funeral feast”.

- “My Flannel Knickers”: a Junji Ito-esque horror piece. Carrington depicts polite society as a nightmarish “jungle of faces”, a social ecosystem in which every being devours every other, and human bodies are merely “ballast” to keep the faces from floating away.

- “Et in Bellicus Lunarum Medicalis”: a Cold War political satire. The medical institutions of Mexico are thrown into confusion when the Soviet Union donates them a team of rats “trained in all forms of surgery”—a gift that no-one wants but it is politically impossible to refuse.

Fini and Carrington both feel like they are stress-testing the very form of the short story—forcing it to the outer limits of possibility to see how far it can go. This kind of experimental energy is what I prize in sci-fi and fantasy, too. At the risk of sounding old-fashioned, I feel this energy has faded in the past few decades as the genre became codified. Hence my fixation upon vintage paperbacks.

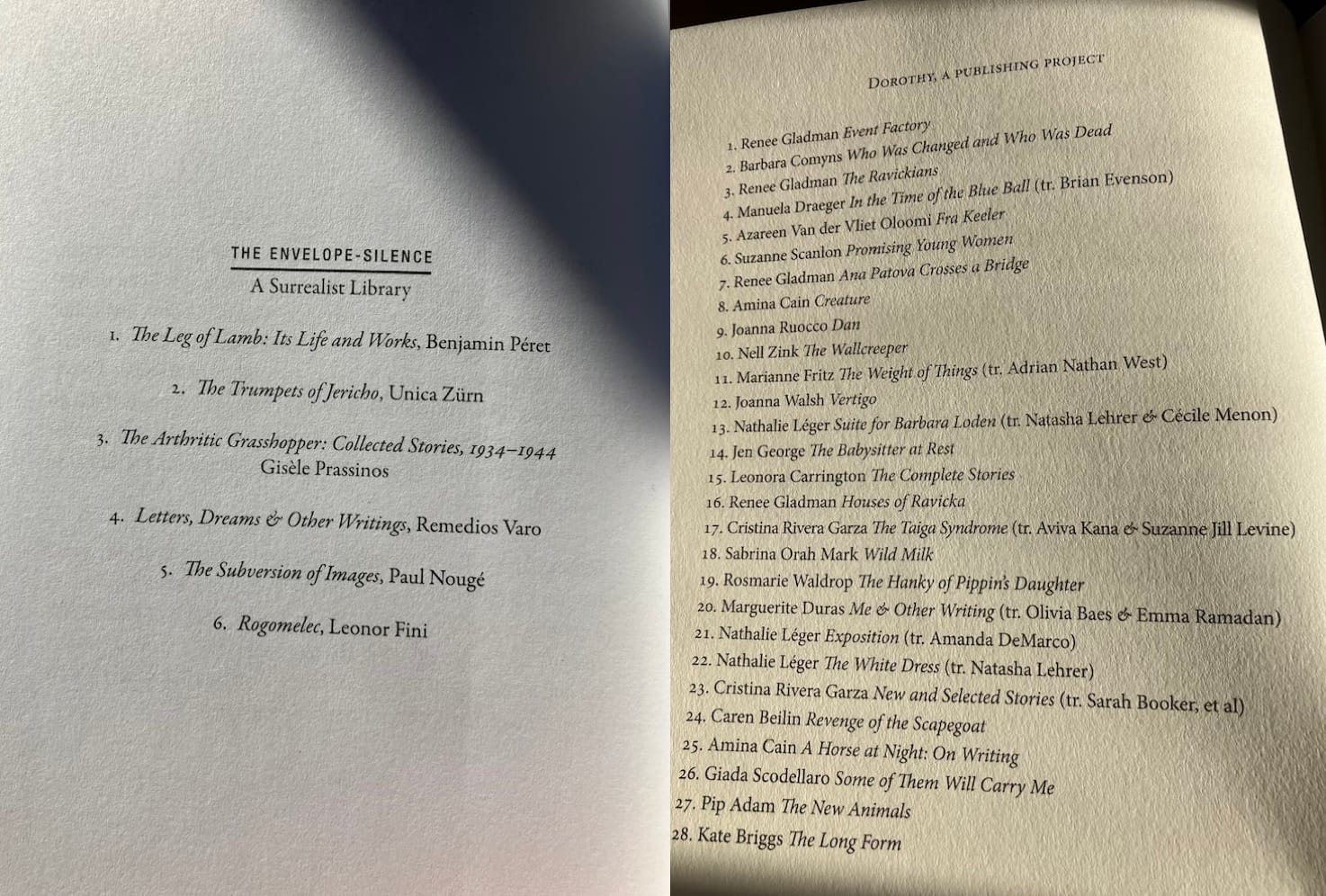

Both Rogomelec and The Complete Stories are published by small presses. Carrington’s book comes from Dorothy, A Publishing Project, and Fini’s from The Envelope-Silence, a series of Surrealist literature. Both books have a list of the press’s other offerings on the last page:

I have never heard of any of these books or authors before. (The one exception is Brian Evenson, and I had no idea he did translation as well as writing his own fiction). To see a list like this gives me a sensation akin to a pleasant vertigo. It is both comforting and frightening to know that there are so many books out there—whole genres, whole artistic movements, which I have not yet explored and perhaps never will.

This is basically the feeling I wish to convey by writing this blog. Literature is like a vast ocean. You can explore it for your whole life and not get to the end of it. Like an ocean it has many different biomes. Dorothy’s selection of titles is one such biome, but you could just as easily drift into any of a thousand others: nature writing, Japanese fair play mysteries, LitRPGs, giant robot poetry…

To read only from the mainstream—the bestsellers, the contemporary releases, even the canon of Western literature—is to swim in only a single secluded bay. What you find out in the open waters may not be good. It may upset or confuse or simply bore you. But it will always be new, mysterious and strange.

Availability: Rogomelec and The Complete Stories of Leonora Carrington are both still in print.

Further Reading

- Nightwell Games is developing Surradia: An Art Retrospective, a puzzle/investigation game based loosely on the lives of Fini, Carrington and other Surrealist painters. I really enjoyed the demo, so I recommend checking it out if you enjoy Obra Dinn-style mystery games.

Member discussion