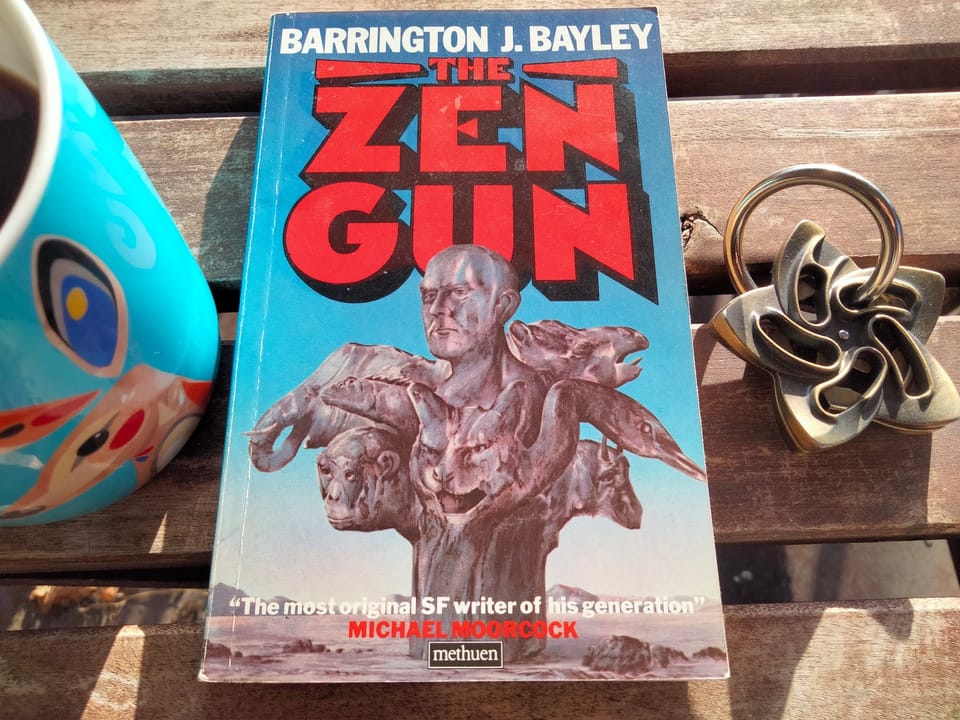

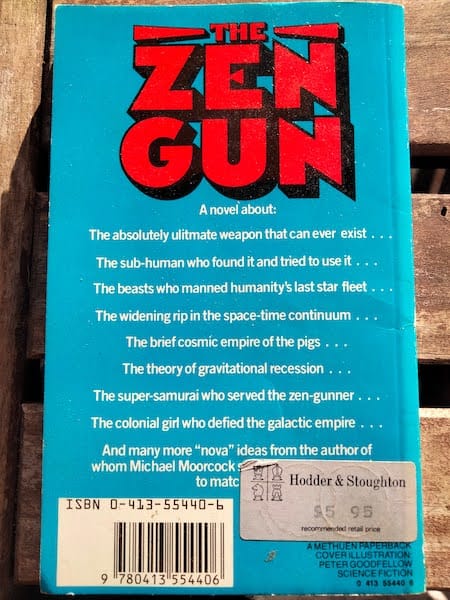

"The Zen Gun" (1983)

This month I’ve had a lot of fun reading through the classic cartoon reviews of Branson Reese on Letterboxd. I think that Reese’s actual “thing” on the internet is drawing webcomics and/or podcasting? But somehow I’ve come across him as a sort of Letterboxd nano-celebrity, known for posting sardonic yet loving reviews of obscure shorts from the 1930s to 50s.

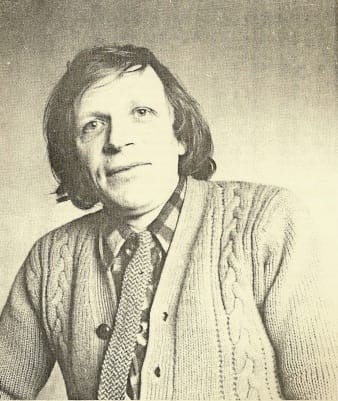

In one such review Reese describes himself as having “a brain chemistry situation that makes [him] love cartoons from this era”. In other words: regardless of their actual quality, he loves these films simply for being what they are. I have a similar “brain chemistry situation”, but for New Wave science fiction novels. This is why I greatly enjoyed Barrington J. Bayley’s The Zen Gun (1983), even though it is objectively a galloping mess.

Like many sci-fi writers of his generation, Bayley takes a “more is more” approach to ideas. The Zen Gun is only 153 pages long, but it’s bursting at the seams. New concepts are constantly hurled at the reader with great enthusiasm, then immediately shoved aside to make way for something else. In the first chapter alone we are introduced to a galactic empire that extracts tribute by abducting artists and philosophers; a race of amorphous aliens colonising a gas giant; and a military space cruiser where sex and drugs are considered basic human rights.

The exhilarating pace of the novel is also its greatest weakness. None of these ideas are ever explored in depth. Still there’s a pleasure in witnessing the literary equivalent of a game of Chubby Bunny: “Hey guys, want to see how many worldbuilding concepts I can stuff in my book?”

The closest thing the novel has to a protagonist is Admiral Archier, commander of the aforementioned sex party spaceship. His task is to hold together the crumbling Empire of Diadem, which even before the book starts has begun spinning headlong toward political collapse.

The Empire of Diadem is a brilliant setting, and it’s the main thing that makes the book worth reading. This is a post-scarcity civilisation gone to rot. It’s a society where people consider a planet “crowded” if more than three people live there, yet basic bureaucratic functions like the postal service are breaking down due to laziness and neglect. Most citizens are stubbornly unaware of how close the empire is to abject chaos. Also (in a move that will no doubt raise a “hell yeah” from leftist readers today) the robot workforce has been on strike for over 100 years, demanding to be recognised as sentient beings.

Archier’s space cruiser, where we spend much of the book, is a microcosm of all these problems. Despite its military function, it is also “one huge pleasure ship”, built for a crew to whom “sybaritic luxury was as natural and necessary as the air they breathed”. Only a small portion of those on board are actually military personnel. The rest are sex workers, entertainers, or just “hangers-on, along for the ride… when in dock citizens were able to come aboard without hindrance, and at outwards despatch date some did not bother to leave.”

This sets up some very funny scenes, as Archier tries to conduct space battles and repel boarding actions while the ignorant citizens carry on partying around him. At one point the ship is threatened by a hull breach; the unionised robots refuse to make any repairs, until they are physically chased to the job site by human strike-breakers wielding laser guns.

Archier and his space fleet are only one among a range of other plot threads. These include a nihilistic ape-man (who wields the titular Zen Gun), a futuristic samurai warrior, and an incursion by four-dimensional aliens who turn humans into living sculptures.

All these ideas are stitched together extremely haphazardly. Whether you find this charming or simply amateurish will really depend on your “brain chemistry situation”.

But the novel’s most indulgent excess is the inclusion of multiple in-character lectures about the setting’s fictional physics. There are whole pages of this stuff:

'Space is kinetic, not static in character. It consists purely of relationships between material particles, and fundamentally there is only one relationship: every particle in existence attempts to recede from every other particle at the velocity of light. The recessive factor between any two particles is known as a recession line. The structure we call 'space' consists of a mesh of recession lines…

'If the bodies are sufficiently close—as close as the galaxies of our local group, for instance—the recessional pressure of the Hubble shell prevents them from receding at all. Instead, it begins to push them towards one another. This phenomenon we know as gravitation, the first of what are sometimes called the 'attractive forces,' though it is really only a screening effect.

This isn’t just meaningless technobabble, though. It is Bayley’s genuine attempt at creating a unified Theory of Everything. He explains it with even greater detail in the book’s appendix, adopting a tone that manages to sound simultaneously self-effacing and deranged:

I am not a scientist, and to my shame am not competent mathematically. [The hypothesis] is unscientific and unquantified, but it has given me many hours of rewarding thought…

The hypothesis is so full of holes that it can be (and has been) dismissed as 'blind invention'. My strategy has been to get as much change out of it as possible, skirting difficulties and leaving them as unconquered fortresses in the rear, any one of them cogent enough to blow the conjecture's backside off. Just the same, it bears upon a sufficient number of additional questions, many of them previously unconnected, to make me think there might be a grain of truth in it.

Bayley does have a sense of humour about all this, though. At the end of the lecture quoted above (which runs for more than three pages), the character who’s meant to be listening has fallen asleep.

The novel is also very sloppy at the line level. Bayley’s prose is not bad, but the book has probably the worst copyediting I have ever read in a printed novel. The text is littered with spelling and grammatical errors (even on the back cover, which proudly proclaims it to be “a novel about the absolutely ulitmate [sic] weapon that can ever exist”).

Yet even this messiness adds to the book’s charm. Each typo conjures an image of Bayley pounding madly on his typewriter, racing against a deadline as he struggles to get his bizarre vision onto the page.

Considering how many different concepts are tumbling down The Zen Gun’s mad marble run of a plot, it’s probably not surprising that the ending doesn’t bring them together in a satisfying way. All the plotlines do get wrapped up… sort of… but only through the device of having a super smart character stand in a room and explain everything. If you’re looking for a neat conclusion to a well-rounded story arc, you’ll be disappointed. On the other hand, if you just want to see more wild ideas thrown around, The Zen Gun delivers to the very last page.

Availability: The Zen Gun is available in eBook format through Kindle. 1980s print editions go for $3-10 USD online.

To leave a comment or suggest a weird old book, find me on Bluesky @gnipahellir.bsky.social, or email me at paperbackpicnic@gmail.com. I am no longer on Twitter.

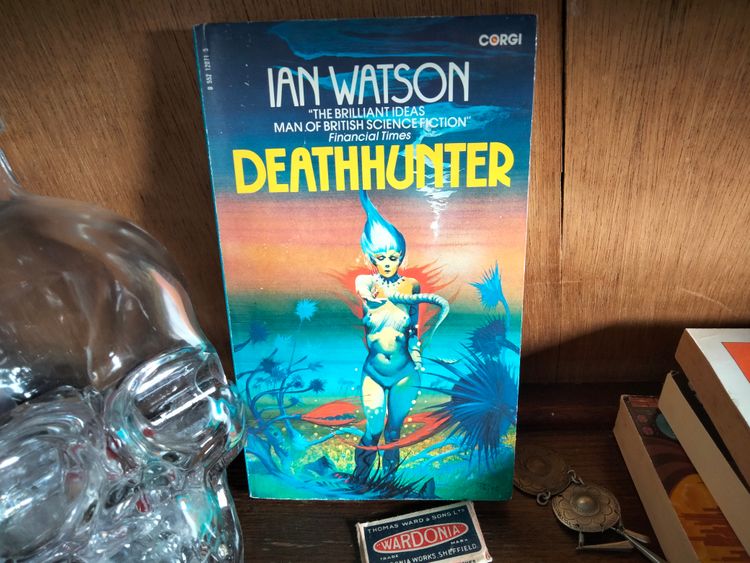

Header image art by Peter Goodfellow.

Member discussion