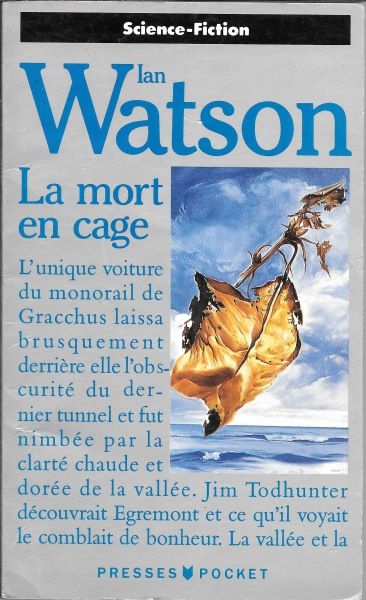

Death is the Soul-Vulture: Ian Watson’s “Deathhunter”

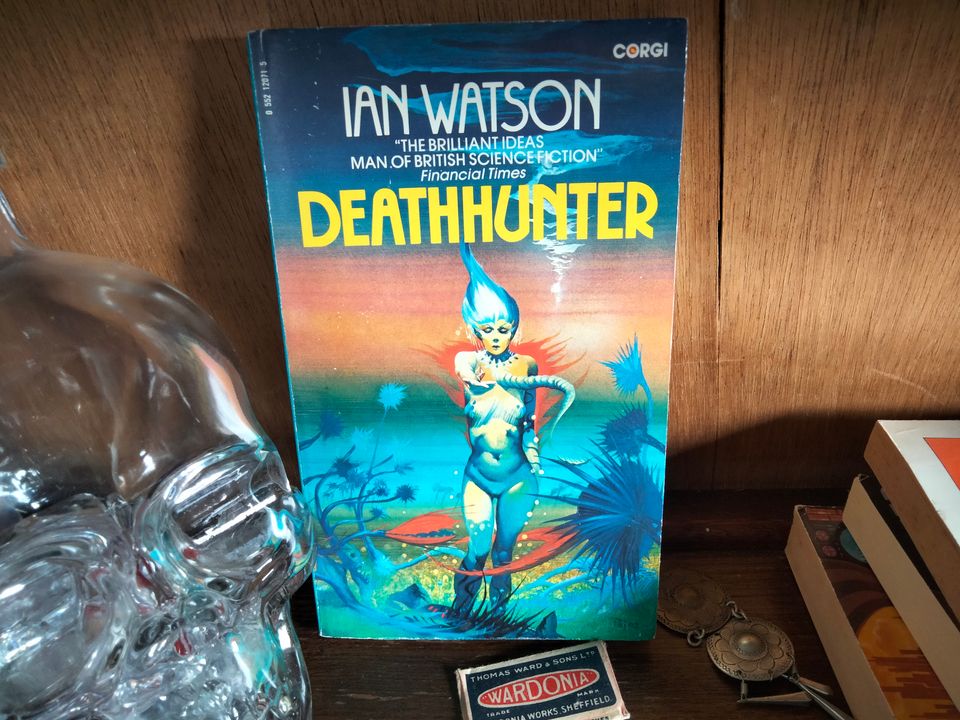

Deathhunter (1981) is the second Ian Watson novel I’ve reviewed on this blog. The first was Queenmagic, Kingmagic, a book that delighted and disappointed me in equal measure. Watson must have been popular among the old SF nerds of my city, as I’ve picked up a fair few of his novels in local second-hand stores.

Deathhunter caught my special attention after I read a comment online suggesting that this novel was Watson’s attempt at a tribute to the proto-fantasy classic, David Lindsay’s A Voyage to Arcturus (1920).

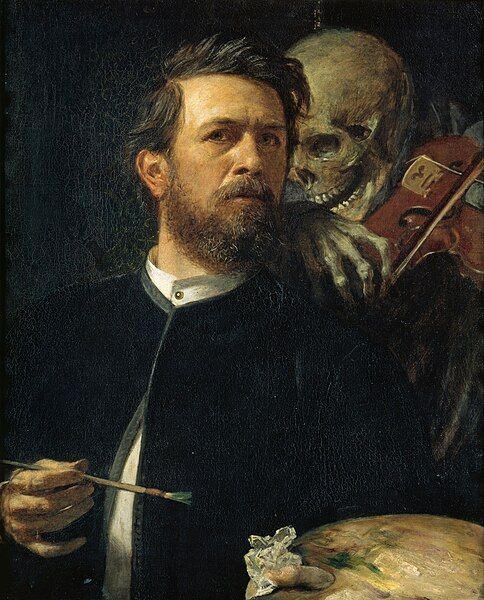

A Voyage to Arcturus is, in my opinion, a masterpiece: one of the most thrilling, fascinating, dream-haunting novels I have ever read. I have often wanted to write about it on this blog; the only thing holding me back is that I really have no words to describe it. The question of what Voyage is really about has been attempted by far finer writers than myself, from Harold Bloom to Alan Moore, and all of them have struggled to encompass it. Nevertheless I will make my own attempt to briefly summarise it.

On the surface, A Voyage to Arcturus is a dreamlike adventure story. It is about an Earth man named Maskull who visits the alien planet of Tormance, where he wanders through bizarre landscapes and meets a variety of strange characters. On a deeper level, Voyage is a metaphysical fable about the search for transcendental truth. For the world of Tormance is a cosmic trap. Every experience there—from love to hate to pleasure to philosophy—is just another illusion to keep the soul from perceiving the true reality beyond. Those who fail to see through the grand lie will be reborn in Tormance eternally (a theme that echoes the philosophies of both Buddhism and Gnosticism).

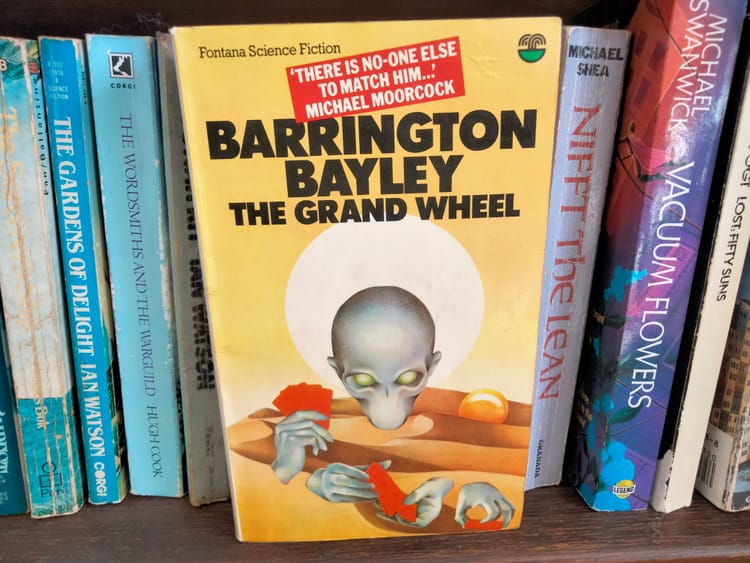

I could go on much longer about Voyage.But for now, Deathhunter. This novel is indeed an homage to A Voyage to Arcturus. There is a good deal of overlap in its themes, as well as a few direct references. Keen-eyed fans of Voyage may even have noticed one such reference on the book’s cover above. Ian Watson actually attempted to write an official sequel to Voyage, but was rejected by the publisher who held the rights to the original.

At first glance, Deathhunter has little enough in common with Voyage. The latter book is set in a psychedelic alien wonderland. Deathhunter, on the other hand, begins in a rather bland future utopia. This is a society built around the peaceful acceptance of death. Our protagonist is Jim Todhunter, a guide in the House of Death. His job is to serve as a psychological and spiritual counsellor, helping people accept their mortality when they are about to die. Anyone who lives past the age of 70 is required to submit to “euthanasia”—though, since it’s non-optional, execution might be a more accurate term.

Todhunter’s entire society depends upon this fierce acceptance of death. Anything that might get in the way of a peaceful passing is banned. Violent films and novels are illegal, since they excite terror of death; conversely, religions that preach of an afterlife are also outlawed.

The theory behind all this—which is expounded at length by the novel’s characters—is that the fear of death is what drives humans to violence against one another. “Friends, we thrived on war—because the survivors of a war had magically defeated death… So we began to plan the biggest war of all—the total war. If we could live through the doomsday of the whole darn world, we really would have punched death in the eye!”

This concept is not without some foundation in psychological research. The field of terror management theory posits that war is a kind of “immortality project”, in which soldiers kill and die precisely so they can “live forever” through the ideal of Nationhood. In Deathhunter, the proof seems to be in the pudding. This death-embracing society enjoys incredibly low rates of violence, war is a thing of the past, and most characters hardly remember how a gun is supposed to function.

On the other hand, the loss of death-fear has led to a kind of cultural flaccidity and a steep decline in the quality of the arts. The novel begins with the murder of Norman Harper, a beloved poet, who produces nothing but inane aphorisms in rhyming couplets:

“The embryo bird must partly die

If its wings are to emerge, to fly.

The caterpillar dies, as well,

To become the butterfly, so swell.”

More generally, this world just seems a bit boring to live in: a bourgeois paradise with all the edges sanded off.

But Jim Todhunter soon stumbles on a secret that could shake this cosy utopia to its foundations. His latest patient is the condemned murderer Nathan Weinberger. In therapy, Weinberger reveals his belief that “death is the soul-vulture”. Death is not an impersonal force, he claims, but a living creature from a higher dimension that harvests human souls.

Weinberger, after spying on Death for years, has come to the odd conclusion that a person’s journey into the afterlife depends more on the manner of death than the events of their life. “Death waits for us—but sometimes we get past it. Sometimes we get through.” Die quickly, and Death the vulture can’t catch your soul; die slow, by disease or euthanasia, and Death will be waiting to snatch you up. By this logic, murder is actually salvation, and the utopian acceptance of death is condemning countless souls to be “caught” by Death.

Todhunter is slowly drawn into the logic of his patient’s “delusions”, until he agrees to help Weinberger in constructing a trap for Death itself. Weinberger serves as the bait by putting himself into a trance-state equivalent to brain death.

The moment when Death appears is the most striking in the whole novel:

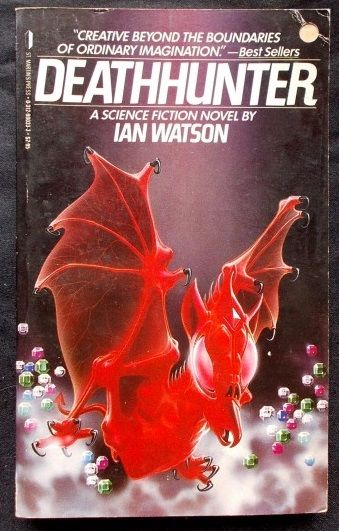

Suddenly something flickered into existence. A red thing—except that it was not really ‘red’—appeared abruptly, perching upon Weinberger’s chest.

It was like a bat, or like a giant moth… It flickered: it seemed to dance in and out of existence. It had big glassy eyes—if they were eyes—as red as the rest of its body. And a cruel little beak. It wore sharp hooks on its veil-like wings—if they were wings—like the spurs of a fighting cock from the bygone years of cruelty…

[Weinberger] sat upright on the water-bier, his eyes wide open. The red thing leapt away from him, flickering, phasing in, phasing out—more in than out. It hit the side of the cage and seemed to pass through the electrified filigree; and through the glass walls too. But no. It passed through, yet not into the room which Jim and Sally shared. It passed through into one of the reflected doubles of the cage—actuallyinto it, leaving no ‘original’ behind in the real cage… Circling outward from the real Nathan Weinberger, the red bat-moth beat from one phantom cage to the next.

This scene alone makes me wish the novel could be adapted into a film—perhaps by Panos Cosmatos of Mandy fame.

This first encounter with the red Death leads to others, and finally to a journey of astral projection in which Weinberger and Todhunter pursue Death into the afterlife beyond.

At last (halfway through the novel) the influence of A Voyage to Arcturus begins to show. The world outside life is a metaphysical ecosystem of soul-catching bats and crystal hells, a ghastly alien universe that would surely have made David Lindsay proud. Weinberger and Todhunter come to understand that the red Deaths are collecting souls and depositing them in “prisms and polyhedra… great jewels, drifting, jostling and rotating within the ether of their flight”.

Each of these crystals contains a private world in which a single soul is trapped forever. The nature of the world depends on the psyche of the prisoner. Some are traditional hells, full of boiling lava or noxious plants. Others are more unusual:

Inside a third jewel, a yellow zircon, was a velvety garden with yew hedges, arbours, bowers, pergolas, gazebos. The garden stretched on and on over hill, down dale. Obscene black statues stood about the lawns and peeked from behind bushes. A naked orgy was in progress on one of the lawns. All the participants had grossly distorted sexual organs, or else their sexual organs were in the wrong place. One man sported a great penis for a nose. Another man’s whole head was a penis with eyes and nose and mouth. Worse yet was a mobile penis on legs which seemed to have been torn out of a giant’s groin and set down to run about. One woman’s face had labia where her lips should have been and nipples instead of eyes; her actual eyes were set in her breasts.

Ultimately, what makes these worlds “hells” is not the nature of their particular contents, but the fact that the soul is forever alone, unable to connect with any other. In a direct inversion of Jean-Paul Sartre’s proposition that “hell is other people”, Watson proposes that hell is an eternity with only oneself for company.

At this point, Watson has constructed a nightmarishly clever twist on the template of Omelas. Here is a utopia for the living that condemns the dead to a terrible fate.

If Watson had been willing to contend with the existential horror of this premise, he might have written a classic of psychedelic science fiction, a book that could be placed proudly on the shelf beside Ursula Le Guin’s The Lathe of Heaven or Philip K. Dick’s VALIS.

Instead, he completely fucks it up from this point onward. (Spoilers follow.)

After some more intrigues on either side of the afterlife, the two heroes escape the “crystal fog” and arrive in a heaven-like space where different souls can visit each others’ worlds. Here they are greeted by the creator of the death-bats, a “red angel” with “wings… of a death’s-head hawkmoth”. This ominous imagery is immediately undercut when the angel conjures up a bottle of whisky for them and proceeds to explain absolutely everything.

Essentially, Weinberger and Todhunter have been completely wrong about the red Deaths’ purpose. Actually, the red bats are not dragging souls into the hell-crystals, but pulling them free into heaven. Thus, the whole meaning of death is reversed: it’s good to die slowly, bad to die quickly, and so, basically… everything is fine and has been the whole time. The ambiguous utopia of the Houses of Death turns out to be unambiguously the best possible society, on either side of the border of death.

This twist is a crying shame, a waste of a brilliant idea. The rest of the book throws in some more surprises, but these only take the plot and characters further off the rails. Sadly, this seems to be a pattern with Watson. Queenmagic, Kingmagic likewise squandered a clever premise on a rushed and ramshackle ending.

Harold Bloom, the famous literary critic, was obsessed with A Voyage to Arcturus. The only novel he ever wrote was, like Deathhunter, a direct homage to Voyage. But Bloom was intensely disappointed with his own novel, and later used it as an example in his theory of “the anxiety of influence”. Simply put, Bloom’s theory states that all authors are influenced by the writers they admire, but they must wriggle out from underneath that influence in order to make their own mark on the literary landscape. Unfortunately, Deathhunter seems like a novel squished under that weight of influence (not just from David Lindsay, but also Philip K. Dick, who Watson cites admiringly in interviews).

I remain hopeful that somewhere in my pile of used bookstore finds, there is an Ian Watson novel that is wholly his own and therefore, perhaps, wholly brilliant.

Availability: Deathhunter is available as an ebook on Kindle or Kobo, and second-hand copies can be found online for $1-6 US.

Further Reading

- It’s about 20 years too young to qualify for this blog, but Vajra Chandrasekera’s The Saint of Bright Doors is one of the best new releases I’ve read this year. I dashed off a simple review on Reddit if you want to hear my full opinion, but the short take is: it’s damn good.

- Goodman Games’ blog has an excellent analysis of my favourite Clark Ashton Smith story, “The Seven Geases” (1934). Bill Ward does a great job of digging into the story’s horror, humour and oblique influence on D&D.

- Ars Technica: The Strange, Secretive World of North Korean Science Fiction

Find me on Twitter @roguesrepast, on Bluesky @gnipahellir.bsky.social, or email me at paperbackpicnic@gmail.com.

Member discussion