"The Wizards and the Warriors": A Lost Treasure of 80s Fantasy

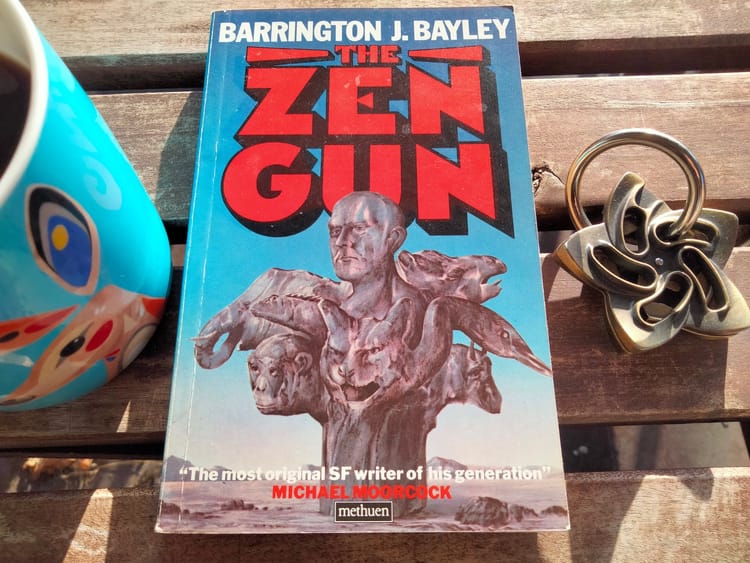

At first glance, Hugh Cook’s The Wizards and the Warriors (1986) presents a very unpromising prospect. There is the painfully generic title, of course, and the bland cover art depicting a stereotypical fantasy landscape. Turn the book over and you will find a blurb comparing it to The Belgariad and The Chronicles of Thomas Covenant, two notoriously bloated Tolkien knockoffs from the wasteland of 80s epic fantasy.

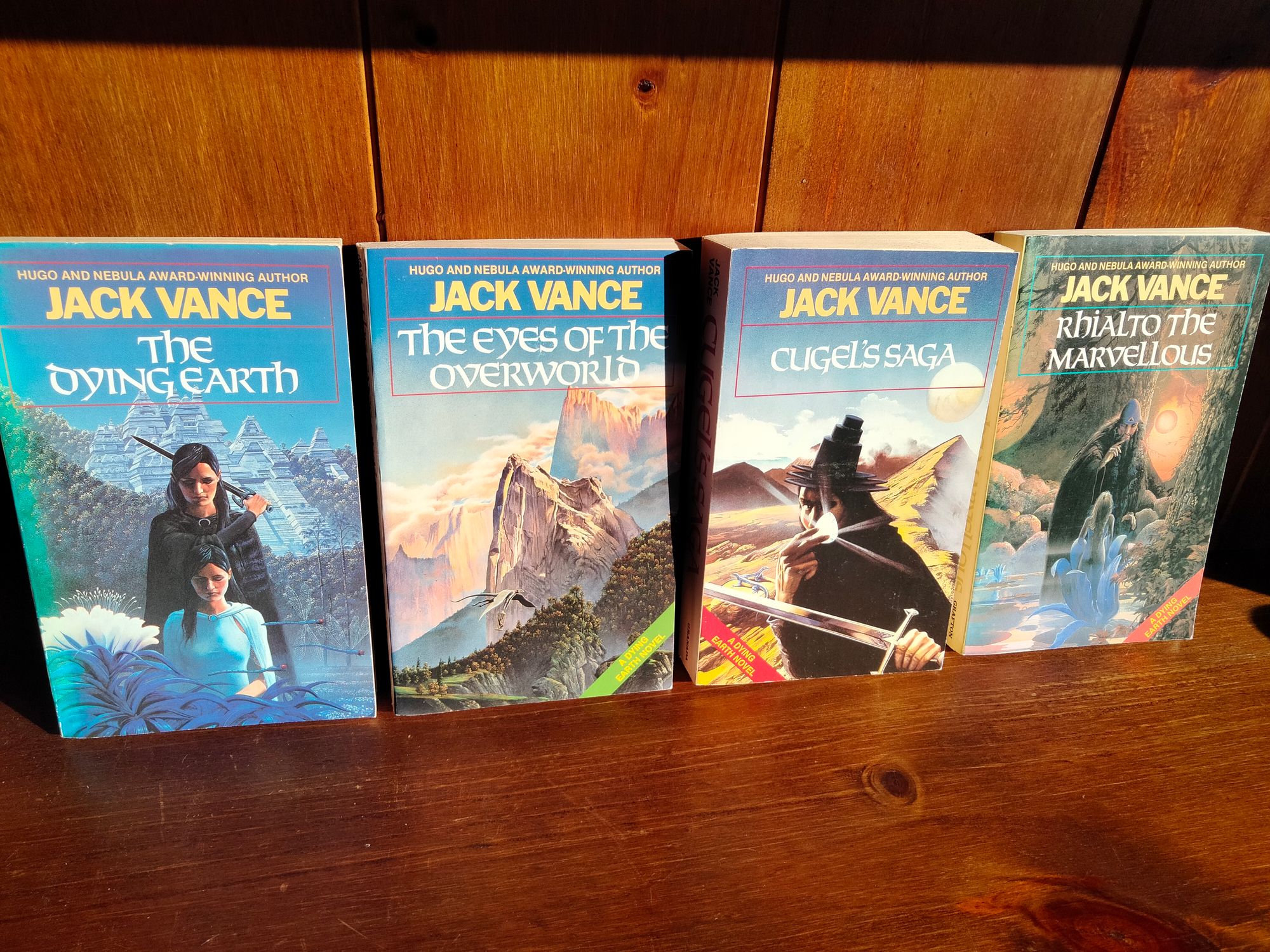

Fortunately, appearances can be deceiving. The Wizards and the Warriors is a hidden gem: a razor-sharp, cynical and very funny novel that feels far more sprightly than a book of 500+ pages has any right to. It has very little in common with the above mentioned mega-fantasies. Instead it draws influence from one of the great Old Masters of fantasy fiction, Jack Vance; and in particular his two wizard-focused story collections, The Dying Earth (1950) and Rhialto the Marvelous (1984).

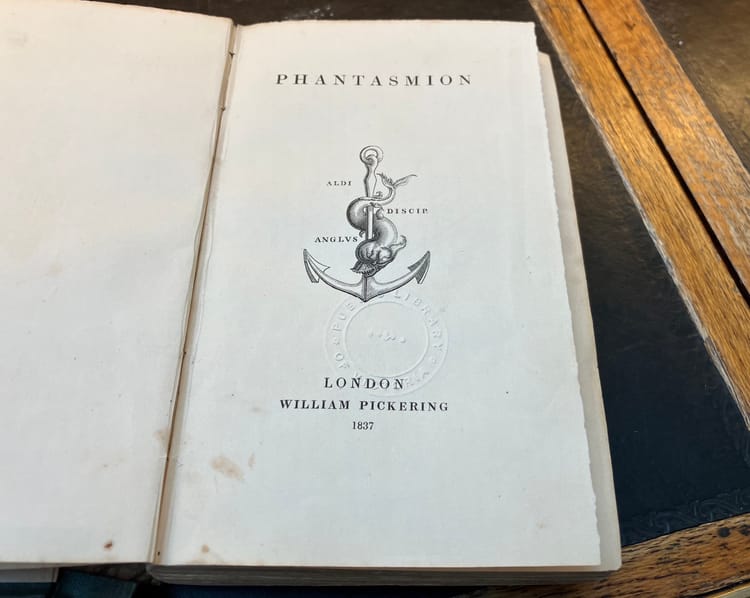

Some of my readers will already be familiar with Jack Vance. If you know, you know. Vance was a writer of unique talent, whose style combined a dry wit with feverish psychedelic imagery.

Vance was also a grand cynic. His novels are filled with greedy and conniving characters constantly scheming to gain power over one another. The wizards of Rhialto the Marvelous are a collection of amoral narcissists, combining all the worst aspects of landed gentry and tenured academics.

Hugh Cook follows Vance’s example in the first chapter of The Wizards and the Warriors. Here we are introduced to three wizards: the pompous Phyphor, his long-suffering apprentice Garash, and the weak but tender-hearted Miphon. They are a self-centred and argumentative trio. But unlike Vance’s wizards, who are only ever looking out for themselves, these three have reluctantly set out on a quest to save the world. They are pursuing one of their own number, the renegade sorcerer Heenmor. He has recently stolen a death-stone (essentially a magical nuclear bomb) and the Council of Wizards are trying to track him down before he makes use of it.

Again, this might sound generic. What fantasy novel doesn’t have a magical knickknack with the power to end the world? But in most such novels, the object would serve as a focal point for a showdown between good and evil. Here the death-stone is more like a MacGuffin in the original Hitchcockian sense of the term: a thing that drives the plot because everybody wants it. It would be a shame to spoil too much, but suffice to say that Heenmor is certainly not an overarching villain in the traditional mould, and the death-stone passes through many more hands before the novel’s twisting storyline is done.

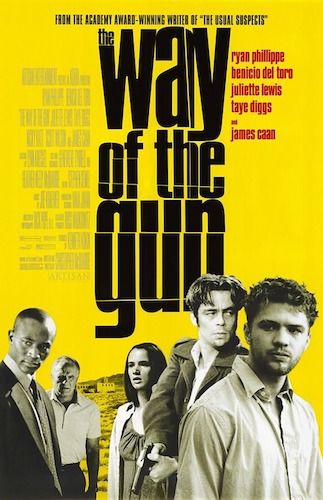

Reading this novel I was reminded repeatedly of a line from the crime caper film The Way of the Gun (2000), in which James Caan’s character comments: “Fifteen million dollars is not money. It’s a motive with a universal adapter on it.” The same description neatly sums up the role of the death-stone. And in fact, The Wizards and the Warriors has a lot in common structurally with crime and noir films. It may be that if Guy Ritchie or the Coen Brothers ever sat down to write an epic fantasy novel, it would turn out something like this. There is a cultivated randomness to the plot: a sense of carelessness toward human lives and desires. Several characters are killed off-screen. Others die by mistake (including one darkly hilarious incident involving a botched prisoner exchange and a skittish horse).

On the other hand, sometimes luck is kind. There is a scene near the end of the book that has the protagonists stumbling by sheer chance on the exact magical item they were looking for. This might have felt cheap if Cook had not already established that all his characters are tossed helpless on the seas of absurd fate.

As the novel’s title implies, the wizards are only half the story. On the other side are the Rovac warriors, a band of elite mercenaries who nurse an ancient grudge against the wizards. The threat (and temptation) of the death-stone convinces the wizards and the Rovac to form an uneasy alliance.

This dichotomy between wizards and fighters is of course an old one that runs through many fantasy novels, and particularly through Dungeons & Dragons, where the two character classes have always been somewhat awkwardly balanced against one another. In thematic terms, the two groups represent two different ideals of manhood (and yes, they are all men here).

On the one hand is the vigorous, self-sufficient warrior; on the other the refined and gentlemanly wizard. The warrior represents independence. He is a man who relies on nothing besides himself. The wizard, on the other hand, is defined by his possessions: his knowledge, his real estate (wizard castles) and his wealth (magic items). The latter two are combined into one in the case of the wizards’ green glass bottle, which contains a labyrinth of rooms hidden inside itself.

These are two archetypal roles. But over the course of the novel, the lines between them get increasingly blurred. The Rovac warrior Elkor Alish becomes obsessed with acquiring magic items to augment his power, even as he is disgusted by the ease with which this magic allows him to massacre his enemies. Conversely, the wizards are confronted by their weakness when it comes to physical violence and practical thinking. Miphon, in particular, learns a painful lesson when he is trapped inside the magic bottle, a situation he could have avoided with even a small measure of fighting skill. This failure haunts him for the rest of the novel, eventually leading to a cathartic reversal in which the wizard becomes the warrior.

A less cynical writer might have framed this whole process like a buddy movie: “We each learned to respect the other’s talents and perspective…” Instead, Cook depicts it as a process of corruption and decay, as men on both sides have their sense of identity broken down by the chaos and violence that surrounds them.

The tone of the novel ranges from humorous to melancholy to bleak. In some ways it feels like a bridge between the wry cynicism of Vance and the more hardcore, “grim and gritty” fantasy of the 2000s—the works of George R. R. Martin, Joe Abercrombie and so on. There are some ugly scenes of torture and mass slaughter, and a griminess to the setting descriptions: “rooves of sodden thatch, dark interiors cluttered with animals, floors of septic mud and manure…” Cook repeatedly takes the time to inform us when his characters are defecating—a detail that most authors have wisely chosen to gloss over. And there are some flippant references to sexual violence that should have been handled with much greater care.

All of this mud-and-shit realism sometimes sits uneasily with the more zany aspects of the novel. But in his best moments Cook successfully fuses the two styles—the grotesque whimsy of Vance and the harsh realism of Martin—to great effect.

In one excellent scene from the latter half of the book, the Rovac warrior Morgan Hearst is in command of an army preparing for a pitched battle. The night before, he issues a complex series of orders, involving irrigation pumps, signal smoke, secret troop deployments and a false feint attack. We are set up to expect a scene of complex strategy and daring gambits, such as we might recall from the Battle of the Blackwater in Martin’s A Storm of Swords, or the enormous climax of Glen Cook’s The Black Company.

But when the battle actually begins, everything goes wrong. Hearst’s inexperienced troops do not listen to his precisely timed orders. They charge too early and retreat too late. A series of mishaps leads to a total breakdown of communication:

'Smoke!' yelled Hearst, to the men manning blazing bonfires. 'Blue—‘ But someone had already thrown a bag of chemicals onto a fire. Red smoke billowed up.

'Blue smoke!' yelled Hearst. 'And sound the retreat!’

A bag of chemicals was thrown onto the fire — this time for blue smoke. A pillar of green and yellow flames shot up into the sky as chemicals mixed. Some of the trumpets sounded the advance, and some the retreat. Wind blew the smoke this way and that, obscuring the battlefield completely.

Then someone threw on black smoke. 'Who threw black smoke!' screamed Hearst. 'I'll kill the man responsible!'

Black smoke was the signal which would summon ships Hearst had waiting upriver. The ships were his reserve force, and this, to his mind, was hardly the time to employ them…

As the smoke cleared, Hearst was able to see that his men were retreating. A few came scrambling up the burial mound; most fell back toward the pyramid, or went mobbing back through the gap between the pyramid and the mound. They were retreating, obviously, not because of the totally incoherent signals, but because they were losing.

The opposing commander’s control of his own troops is hardly better; the battle dissolves into a chaotic melee in which strategy counts for nothing.

The whole scene is at once brutally realistic and extremely funny. It also cuts incisively to the underlying theme of pure chance overwhelming the agency of human beings. After the battle, what matters most to Hearst is not who won or lost, but that his own plans and decisions had practically no impact on the outcome.

All the main characters grapple with randomness in their own way. “We’re dice,” one character states, “and we’re rolling. How we fall is not up to us.” By the end of the novel, the survivors are worn down and disillusioned, confronted by the fact that they have survived and others have died only by luck, and not by any innate qualities of character.

This fatalistic attitude is oddly fitting for a novel with a somewhat tragic backstory. The Wizards and the Warriors was originally planned as the first in a series spanning a whopping sixty novels (divided into three cycles of twenty books each). This may seem comically overambitious until you learn that Cook did, in fact, write the first ten of these novels in the period from 1986 to 1992, pumping them out at a rate of 1.25 books per year. It seems it was not a lack of will that put an end to the series, but low sales numbers. Although Cook continued to write prolifically until his death in 2008, he never returned to the setting.

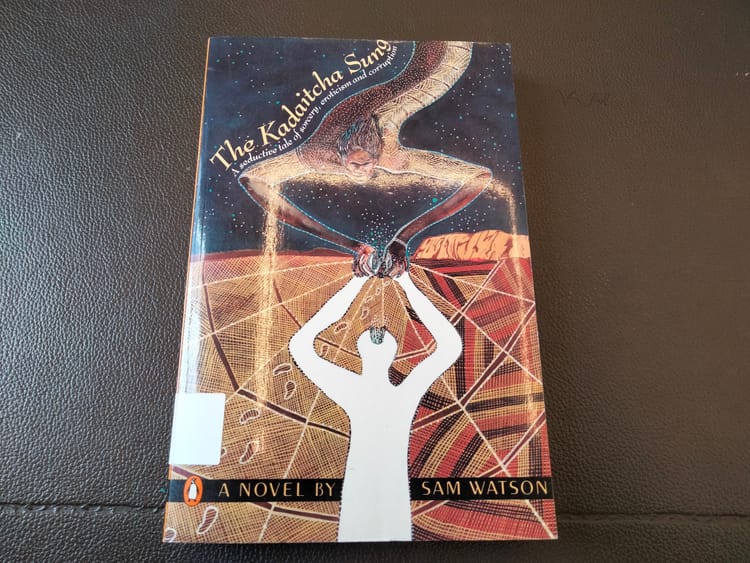

Nevertheless, the series has a small but ardent fan community, with its own subreddit and a charmingly old-fashioned wiki. I have yet to read any of the later novels, but they apparently open up new vistas of setting and style, with characters crossing over and revisiting the same events from different perspectives. Only last week I was lucky enough to find the second book, The Wordsmiths and the Warguild, for $2.99 at a charity shop. I eagerly await the opportunity to read it and report back in a future instalment of this blog.

If you’ve got an opinion to share, or a weird book you think I should know about, you can find me on Twitter @roguesrepast, on Cohost @willgreatwich, or email me at paperbackpicnic@gmail.com.

Member discussion