Liminal Labyrinth

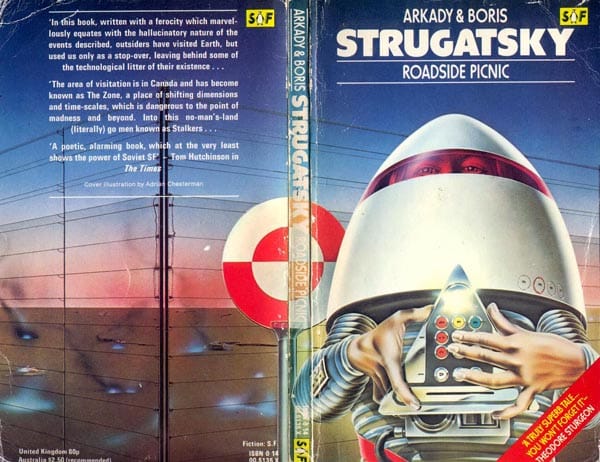

The descent into the underworld is a concept almost as old as human imagination itself. It occurs across continents and civilisations from Mesopotamia to Central America. For Carl Jung it represented a journey into the depths of the unconscious mind. For Joseph Campbell, it was an aspect of the universal “monomyth” that underpins all human storytelling.

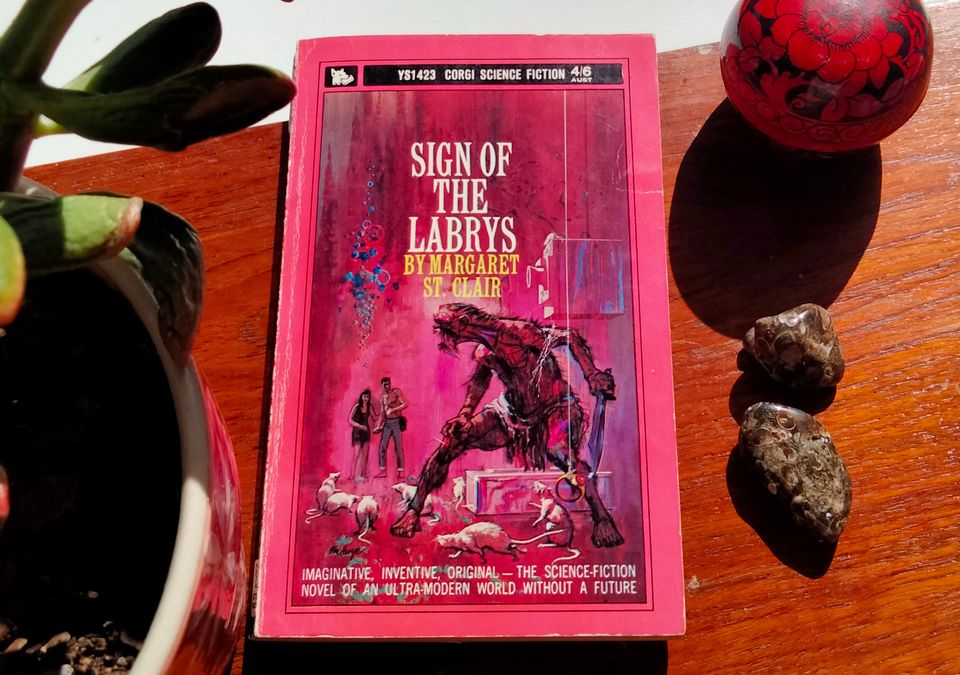

Margaret St. Clair’s Sign of the Labrys (1962) is, literally and figuratively, a story of a journey into the underworld. But instead of a dark primordial cavern, this underworld is a brightly lit labyrinth, built of concrete and steel, conceived by the blandly irrational minds of military subcontractors.

Perhaps St. Clair touched something that resonated there, straddling the gap between old story and new myth. Because, for such an obscure text, Labrys has had a surprising, hidden influence on popular culture through the 60 years since its publication. But we’ll get to that.

First the story. It begins, of course, on the surface. Our protagonist is the bland everyman Sam Sewell, who leads a dreary and directionless life in the aftermath of a catastrophic pandemic. This “yeast plague” has wiped out the vast majority of the human race; the survivors live either on the blighted surface, where the ground is still littered with unburied corpses, or else in huge underground complexes originally intended as nuclear fallout shelters. People tend to live alone. Although the worst of the plague is over, it has left a deep psychological revulsion toward human contact. Sewell drily reports: “People satisfy their sexual needs in fifteen-minute contacts, and run away from each other afterwards.”

Isolation aside, the people of this fallen world are surprisingly content. St. Clair nimbly reverses the standard tropes of post-apocalyptic stories in which survivors struggle over scarce resources; instead her characters live in a state of abundance. The bomb shelters are stocked with huge reserves of food and medicine, and since the human population has been reduced so drastically, it will take generations for the supply to run out. If they ever get sick of canned goods they can also eat the purple fungus that grows in the lower caverns. (As you may have already noticed, a strong fungal theme runs through the whole book).

Sewell has a job, but it is pointless: he moves boxes back and forth across the floor of a warehouse. He is paid in food vouchers that he doesn’t need. He and the other workers play out a vestigial pantomime of the way society worked before the end of the world.

Soon, though, Sewell’s life is disrupted by the meddling of two competing factions. First there is the FBY (“Federal Bureau of Yeasts”), a lone vestige of the US government with a creeping fascist agenda. Set against them are the Wiccans, a conspiracy of counterculture witches.

Oh, didn’t I mention this post-apocalyptic novel also has literal magic in it?

Wiccans, of course, are not a fictional invention. They are a real religious movement, a revival of European paganism founded by Gerald Gardner in the 1940s. (Gardner himself claimed to have received the tradition from a hidden coven of witches in the New Forest, but the evidence for their existence is questionable at best.)

Margaret St. Clair was herself a Wiccan. In fact, she was apparently one of the religion’s earliest adopters in the United States, and this novel is one of the first sources anywhere in the world to use the term “Wicca” rather than the more generic “witchcraft”.

St. Clair’s interest in “the craft” runs deeply through the novel, and gives its magic a very different quality to most modern fantasy. The Wiccans’ magic is real, but it is subtle, psychological, and slow-moving. It depends more on trickery and illusion than direct control of elemental forces. Ritual plays an important role, as does drug-taking (this is a 60s novel) and sensory deprivation programs. There is a sense that magic’s internal effect upon the practitioner is at least as important as the external effect upon the world.

Sewell soon begins to discover his own magical powers. But to unlock their mysteries, he must go down, deeper into the underworld, in search of the witch-queen Despoina.

The underworld really is the star of the show here. Sign of the Labrys is a pretty mediocre book in a lot of ways: the prose is dull, the characters inconsistent, the plotting slovenly. The book is carried by its wonderful setting, a concrete labyrinth at once coldly industrial and mythically mysterious.

In some ways this underworld is welcoming, even homey. There are apartments with running water, communal kitchens with working gas stoves. When Sewell is hungry, he picks up a can of meatballs from the nearest storage room. In other ways it is fantastically dangerous: there are traps throughout, including guns that protrude from walls and an overcharged x-ray machine that projects a deadly beam of radiation. Secret passages connect one level to the next, sometimes opened only with special keys.

As one goes down, it gets difficult. Entrances and exits are usually concealed. The reason for this, I think, was partly to protect the VIP’s in the lower levels from unauthorized intrusion, partly to provide a redoubt in case the “enemy” was victorious, and partly because of the passion for secrecy that characterizes the military mind.

Whatever the reason, the difficulty exists. F is said to be the last of the levels one can enter easily.

Readers looking for a visualisation of this uncanny setting need look no further than the internet aesthetic of “liminal spaces”, which documents the eerieness of human architecture where actual human being are absent.

It is the quiet, empty moments in the novel that are the most compelling. At one point, while fleeing from FBY agents, Sam and his witch companion Kyra escape through a secret trapdoor in the ceiling. This leads to a long vertical shaft connecting one level to another. Halfway up the shaft is a hidden room concealed behind a wall of lichen, which “looks just like the chute” but “break[s] away like peanut candy”. Inside the room is “an unpainted wooden floor... a wide bunk and a chemical toilet discreetly visible behind a screen”. Discussing the empty room’s purpose, Kyra speculates it was built by a military architect with too much money on his hands:

“The levels are full of foul-ups and bright ideas that didn’t work... I imagine the designer had some sort of notion of guerilla fighters resting here between sallies out to harass the enemy after they had taken level F. But I really don’t know. Perhaps he was only trying to bolster up the economy by spending a little more cash.”

(To be honest, this unknown designer might be a more interesting character than many of those with speaking roles in the novel.)

Many other such details haunt the pages. There is a pool containing the calcified skeleton of a businessman with his briefcase; a room infested with white lab rats gone feral; and a hall of subterranean windows, each one opening onto a tiny diorama of a suburban scene. At one point the characters travel through a vast abandoned mall. Sewell comments: “I suppose the idea was that people would while away the time they were in the mass shelter by buying souvenirs to take back to the surface with them.”

Like any good underworld, the bomb shelter gets stranger the deeper you go. It is divided into a series of layers or levels, labelled alphabetically. From A down to E is residential, still mostly part of the “surface world”. Sewell’s quest really begins when he descends to F, a level of mad science laboratories and medical tests. It’s here that he meets Kyra, a fellow Wiccan and fungus expert. The next level is G, where a cloistered community of the ultra-wealthy lives in ignorance of the surface world. Kept eternally young by plastic surgery, and blissed out on euphoric drugs, they present a modern reflection of the old stories of fairy revels under the hills.

Level H is a military maze, built around the now-empty command centre of the U.S. President (another liminal space if ever there was one). The deepest of all is Level I, which consists of natural caverns, the ancient substrate of the entire shelter complex. Here at last Sewell finds the great Despoina. Under her supervision he is initiated into the mysteries of Wicca (a process that involves a good deal of nudity and a whipping from a man in a stag mask).

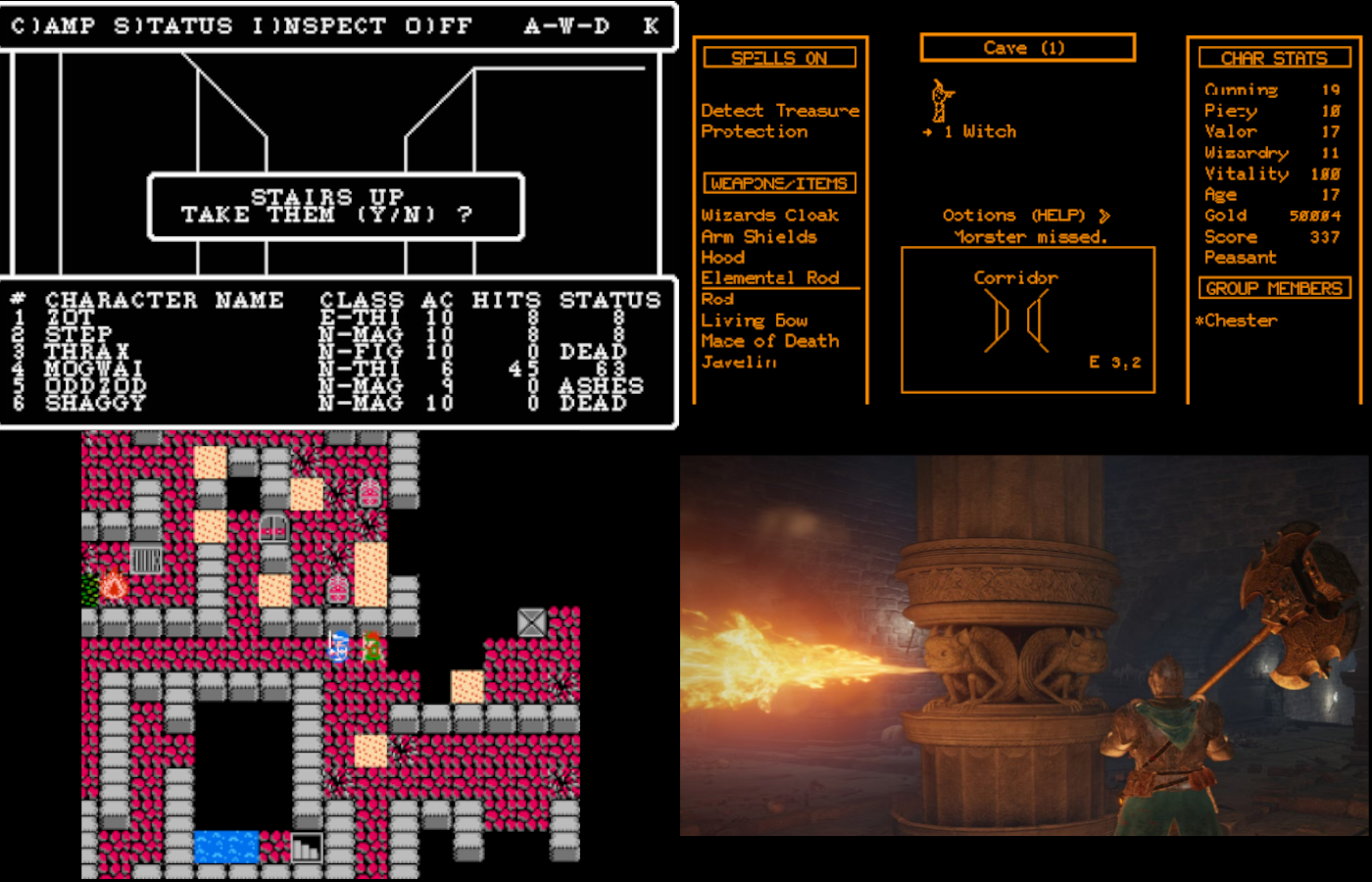

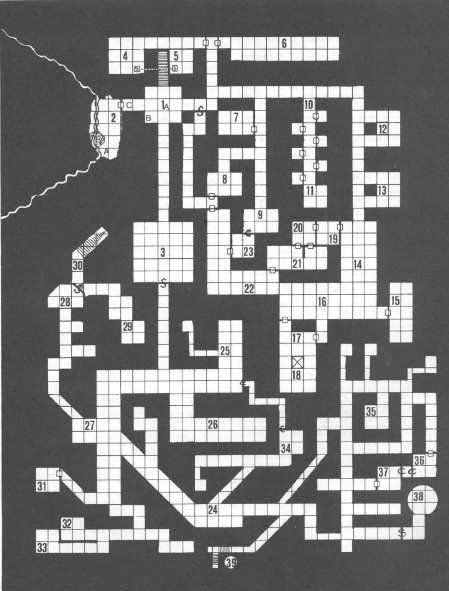

This whole underground space—the levels, the traps, the secret passages—might sound familiar to some readers. That’s because Sign of the Labrys has cast a surprisingly long shadow over pop culture, particularly gaming culture. See, this is one of the books cited by Gary Gygax in his legendary “Appendix N”: a list of works that inspired the development of Dungeons & Dragons. And the traces of this particular novel are very evident in early D&D. Gygax’s first games were set in the tunnels beneath Castle Greyhawk, where adventurers delved progressively deeper in search of treasure. Just like St. Clair’s underworld, these tunnels were divided into distinct levels, populated by traps and monsters, and connected by secret passages and teleporters. (A climactic scene late in the book features Sewell and Despoina struggling to activate a “matter transporter” so they can get back to Level H.)

Of course, Gygax’s version of the underworld was medieval in character, not modern. But it’s noteworthy that real-life dungeons and castles, just like bomb shelters, are products of “the military mind”.

Castle Greyhawk was the first of what D&D players today call “megadungeons”. The trope of a huge subterranean labyrinth has become a beloved pillar of the game. But Labrys’s afterlife doesn’t end there.

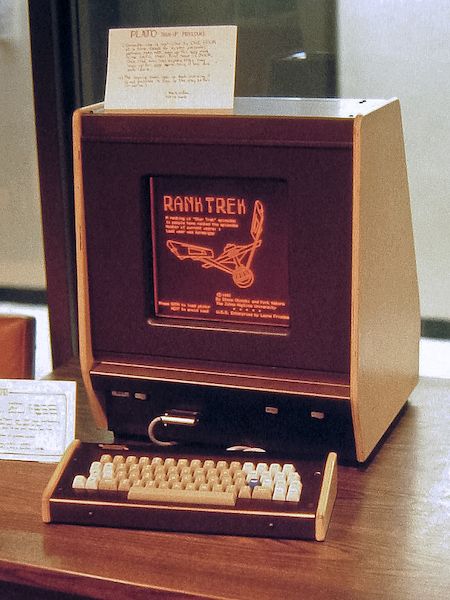

The original Castle Greyhawk games took place in Gygax’s hometown of Lake Geneva, Wisconsin. Meanwhile, just a few hours’ drive away at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, students were experimenting with some of the world’s first computer games. These games ran on the university’s PLATO IV system, a kind of primordial ancestor of the modern internet. It had bulletin boards, live messaging and real-time gaming, all accessible through hundreds of video terminals on and off campus.

As D&D spread through geek culture in the mid-1970s, PLATO users began trying to replicate the tabletop experience and created the world’s first computer RPGs. The earliest of these was bluntly named dnd; it was followed by Oubliette, Moria and others (the university administrators kept deleting these “frivolous” programs to save precious storage space).

Pretty much all of these early CRPGs adopted the megadungeon format. It was a simple way to add progression and challenge: the deeper you go, the more dangerous it gets. Surprise traps and teleporters were also common features. It wouldn’t be right to say that this shows an exclusive influence from Margaret St. Clair: Conan the Cimmerian dodged traps as well, and secret passages are a staple of fantasy all the way back to Gothic fiction. But the line of descent is definitely there.

The next evolution of these text-based dungeon games was Rogue (1980), the grandfather of the now broadly popular roguelike genre. Meanwhile, Oubliette had a strong influence on Wizardry (1981); Wizardry was imported to Japan where it inspired Dragon Quest (1985); and Dragon Quest laid the blueprint for more or less every Japanese RPG ever made.

As a result, faint traces of Sign of the Labrys can still be found in videogames today, from Elden Ring to Hades: underworld journeys, trapped corridors, secret passages hidden behind illusory walls. Not bad for a book that was out of print by the late 1960s.

Does influence like that happen for a reason, or is it just dumb luck? Probably the latter. But humour me, and entertain the idea that there was something special in St. Clair’s novel that made it resonate through the decades, even with people who had never heard of the book itself. If that somethingexists, I would venture a guess that it is the novel’s unresolved tension between two worlds: reason and unreason, modernity and mystery.

Most writers working with the underworld journey describe it in terms of a binary opposition. The ordinary world is the antithesis of the underworld. Above is order, reason, light. Below is chaos, darkness and the unconscious. But Sign of the Labrys continuously blurs the lines of that distinction.St. Clair’s labyrinth is a modern place, built on scientific principles. The heroes who delve into it are witches, wielders wielders of ancient and chthonic power. But then again, St. Clair repeatedly highlights the irrationality of the labyrinth’s designers: their pointless expenditures and paranoid boondoggles.

Nuclear war, though it doesn’t appear directly, casts a shadow over the book. The labyrinth itself was built as a fallout shelter, and we eventually learn that Kyra, the witch-mycologist, released the yeast plagues on the world in an effort to prevent imminent nuclear armageddon. And what is nuclear war but the ultimate military boondoggle: the waste of absolutely everything?

Speaking of Kyra: she’s both a witch and a scientist. In one scene she evades her enemies by combining magical illusions with hallucinations induced by fungal spores. In another, she offers Sewell “a drug psychiatrists used to use to combat depersonalisation”—to help him keep his soul inside his body when he teleports.

Science and magic, rational and irrational. Far from being polar opposites, in Sign of the Labrys these things are inextricably tangled together.

This tension remains fruitfully unresolved in Labrys’s many descendants. Consider the role of the Dungeon Master: constructing a “mythic underworld” that is supposed to be wild, uncharted, unknowable, and yet at the same time is painstakingly mapped out on graph paper in units of 10’ square. Or look at computer RPGs, where a major selling point is the thrill of venturing into the unknown, yet the statistics of characters and monsters are obsessively catalogued and quantified. We chase ancient myths through a labyrinth of hard numbers—or vice versa.

Why does this tension continue to compel us, sixty years on? Perhaps only because it reflects the way we live now. Our lives are governed by numbers. Relentlessly our society pursues order, efficiency, improvement, reason. But the other side, the unreasonable side, is not gone. Tucking it away in the underworld was only ever a metaphor. Pave it over with concrete, turn on all the lights. Still it is there, in all of us.

—

If you’ve got an opinion on this post, or a weird book you think I should know about, you can find me on Twitter @roguesrepast, on Cohost @willgreatwich, or email me at paperbackpicnic@gmail.com.

Member discussion