Phantasmion: The First Fantasy Novel

In a previous post, I speculated that Sara Coleridge’s Phantasmion (1837) was the first story set in a completely secondary world. Now that I’ve read the book in full, I’m going to go further and say this may be the earliest book recognisable as what we’d now call a fantasy novel.

Defining the beginning of a literary genre is always a bit arbitrary. If we take “fantasy novel” to mean the modern marketing category, then the crown of “first” probably goes to The Hobbit or The Lord of the Rings. If we broaden the definition to include any story involving magic or the supernatural, then we could project it all the way back to the Epic of Gilgamesh.

Phantasmion sits somewhere in the middle. It has all the elements we would expect from a modern fantasy novel: magical powers, fictional nations, heroes, battle scenes and love triangles. And although it shows its age in a few spots, overall it’s still an entertaining read with moments of genuine brilliance.

The basic plot is a classic and arguably cliched one. Phantasmion, the young prince of Palmland, falls in love with the fair princess Iarine. To win her hand, he must overcome the treacherous general Glandreth of Rockland, who is secretly planning to invade Phantasmion’s kingdom. The default assumptions about gender are obviously a bit regressive. But Iarine is not just a helpless damsel, and she gets a decent number of scenes in which to do some adventuring of her own.

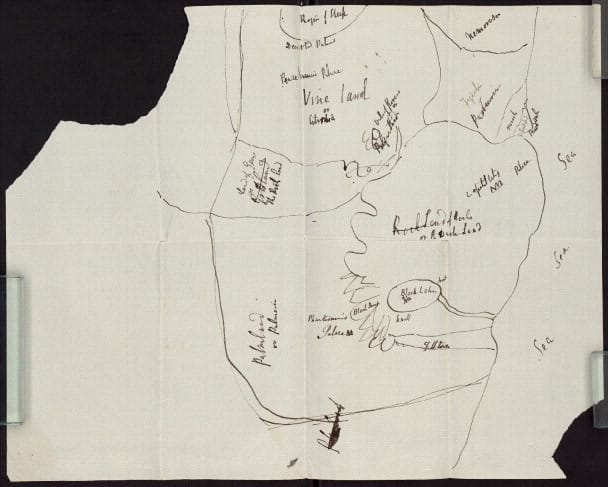

Clearly, Phantasmion owes a lot to the fairy tales and chivalric romances that came before it. Why then do I class it as the first fantasy novel? Firstly because it is a novel, rather than a shorter story, an oral narrative or an epic poem. And secondly because—as Matthew Surridge at Black Gate points out in a very comprehensive article—this is the first story set in a fictional world with its own politics and geography. Place names in the novel like “Almaterra” and “Tigridia” would not look out of place in a fantasy novel from the 2020s. Moreover, Coleridge makes a clear effort at what we would now call worldbuilding. These nations are not just vague outlines for the heroes to adventure in. They have their own histories, territories, and material concerns. For example, the war between Palmland and Rockland arises from a struggle to control valuable iron mines on the nations' border. This isn’t just a throwaway detail, either: the lack of metal armour for Phantasmion’s soldiers is actually a key plot point, which leads to a brilliant set piece that takes place in a fairy foundry at the heart of a volcano.

Phantasmion is not a particularly easy book to read by modern standards. The writing has a sing-song cadence that becomes grating over the length of a whole novel. This problem is compounded by the enormous wall-of-text paragraphs—apparently in the 1830s paragraph breaks were a limited resource. But there are times when the prose rises to spectacular heights, as in this passage describing Phantasmion’s encounter with the angelic wind-spirit Oloola:

Phantasmion started up and saw the pinnacles of the edifice gilded, here and there, by partial beams, which struggled forth from amid disorderly heaps of dark vapour. Just beyond the battlements of a black tower, he beholds transparent pinions, spread to their vast extent, with the sun glittering through them. A moment afterward they recede; Oloola dives among the clouds on which those golden wings shed radiance. On she goes, sweeping the sky, as a shearer sweeps away the fleeces of the new-shorn flock; and now she is indistinguishable from the mass that moves along with her, and now both she and the clouds themselves are gone, leaving the cope of heaven pure and resplendent, as if it were cut out of a single sapphire, through which a powerful sun was pouring its diffusive light.

On top of being a fantasy novel, this is also a superhero story of sorts. In the first chapter Phantasmion earns the favour of Potentilla, the Fairy Queen of Insects. In a plot device that feels closer to Stan Lee than J. R. R. Tolkien, Potentilla explains that she can bless Phantasmion with the powers of any insect, but only one at a time. This leads to many creative scenes as Phantasmion swaps out his powers to fit the situation, gaining at different times the wings of a dragonfly, the leap of a grasshopper, and the digging skills of an antlion, to name just a few.

To balance these powers, Phantasmion’s rivals each have their own fairy godmother to help them. The young prince Karadan is backed up by Seshelma, a mermaid-like figure with powers of electricity and poison; while Glandreth, the old general, is supported by the aforementioned Oloola.

These three men are the movers and shakers of the story, but they are effectively helpless without their female patrons. From one angle, you could view the three fairies as subservient to the male characters and their desires. But the fairies can also be read as metaphorical mother figures, watching over and indulging their surrogate sons.

Sara Coleridge originally wrote Phantasmion as a fairy-story to entertain her young son Herbert. It's easy to see a similar relationship between Potentilla and Phantasmion. The fairy queen grants powers to the young prince like a mother giving toys, and he takes a childlike joy in using them: leaping across lakes as a grasshopper, or cheekily tormenting Glandreth with noises from his cicada-like diaphragm.

Potentilla may represent an idealised mother-figure, but there are also real mothers in the novel. In contrast to the fairies, these mortal women express human frailty and sorrow. Some, like the witch Malderyl, stoop to evil magic in order to help their sons succeed. Others, like the queen Arzene, are separated from their children by cruelty or misfortune. All the mothers in the book eventually die in tragic circumstances.

Coleridge’s own life was haunted by death and despair. Two of her four children died in infancy around the time of Phantasmion’s composition. She suffered from depression, anxiety, ill health and opium addiction. The writing of this novel, so full of youth and beauty, seems to have been a deeply personal effort to light herself a candle amidst the darkness of grief.

Grief is everywhere in Phantasmion, submerged but ever-present. In the first chapters, Phantasmion’s child playmates die abruptly after eating poisoned flowers. They are followed soon after by Phantasmion’s mother and father. Characters like the mad king Penselimer are haunted by grief for those they have lost. In one scene, Iarine comforts her young brother with descriptions of heaven, but he seems unconvinced:

"Heaven is happiness," the maid replied; "all that can make us happy we shall meet there."

"I wish," said Albinet, with a sigh, "that we could get thither without going down into the dark grave. Is there no lightsome road to heaven, up in the open air?"

For the most part Phantasmion is an upbeat novel, which celebrates the beauty of imagination and the vigour of youth. But behind this there is also the knowledge of youth’s impermanence. Flowers appear frequently in the novel, but their bright blooming is always contrasted with the moment their petals begin to fall. After every spring comes winter, as in this verse recited by the melancholy damsel Leucoia:

When the joyous months are past,

Roses pine in autumn’s blast,

When the violets breathe their last,

All that’s sweet is flying;

Then the sylvan deer must fly,

‘Mid the scatter’d blossoms lie,

Fall with falling leaves and die,

When the flow’rs are dying.

This, too, is something Phantasmion has passed down to the fantasy literature of the 20th century. Confrontations with grief and mortality lie at the heart of many of the genre's most powerful moments, from Frodo's departure for the Grey Havens in The Lord of the Rings, to Ged’s battle in the Dry Land at the climax of The Farthest Shore.

When reading an early work of fantasy like this one, I'm always interested in lines of descent. It's one thing to say that Phantasmion is like modern fantasy novels, but can we prove that it actually influenced them? The answer seems to be yes, albeit indirectly. Coleridge's novel had a distinct influence on George MacDonald, another proto-fantasy author. MacDonald, in turn, was read by Tolkien, C. S. Lewis and Ursula Le Guin, among many others. In this sense, Phantasmion really has achieved a kind of triumph of imagination over death. Though Coleridge and her children have long since “gone down into the dark grave”, the story she told is still with us today.

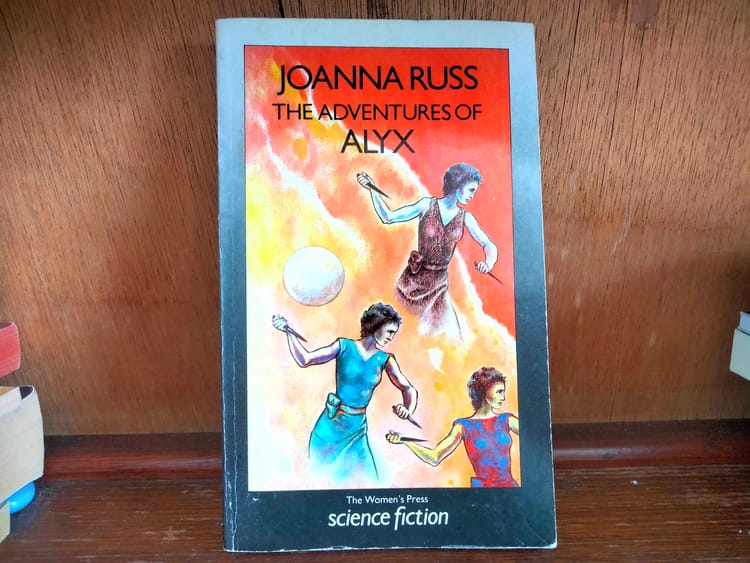

Availability: Phantasmion is readily available in eBook format. The cover image is a first edition copy I photographed at the State Library of Victoria.

Further Reading

- This month I had an article published in the inaugural edition of Typebar Magazine. I wrote about the cult animated series Aeon Flux and its prescient relationship with modern television.

- Speaking of Typebar, I’ve been generally impressed with the quality of the writing they’ve put out. I particularly enjoyed this piece by Gwen C. Katz on how 19th-century astronomical theories influenced early science fiction; and this review by Eric de Roulet that makes an impassioned case for the role of literary prose in fantasy writing.

- Deep Cuts in a Lovecraftian Vein has a gloriously obsessive catalogue of Lovecraftian movie posters from Ghana.

To leave a comment or suggest a weird old book, find me on Bluesky @gnipahellir.bsky.social, on Cohost @WillGreatwich, or email me at paperbackpicnic@gmail.com.

Member discussion