The Adventures of "The Adventures of Alyx"

I have a bad habit of reading only the "minor" works from a famous author. For instance, there was a long period when the only Virginia Woolf I had read was her weird time travel novel, Orlando. Around the same time, the only Umberto Eco I had read was his zany Medieval fantasy novel, Baudolino. I think it’s a contrarian impulse inside me—probably the same impulse that leads me to write this blog. Perhaps it's as simple and selfish as wanting to feel like I've discovered something that no-one else has.

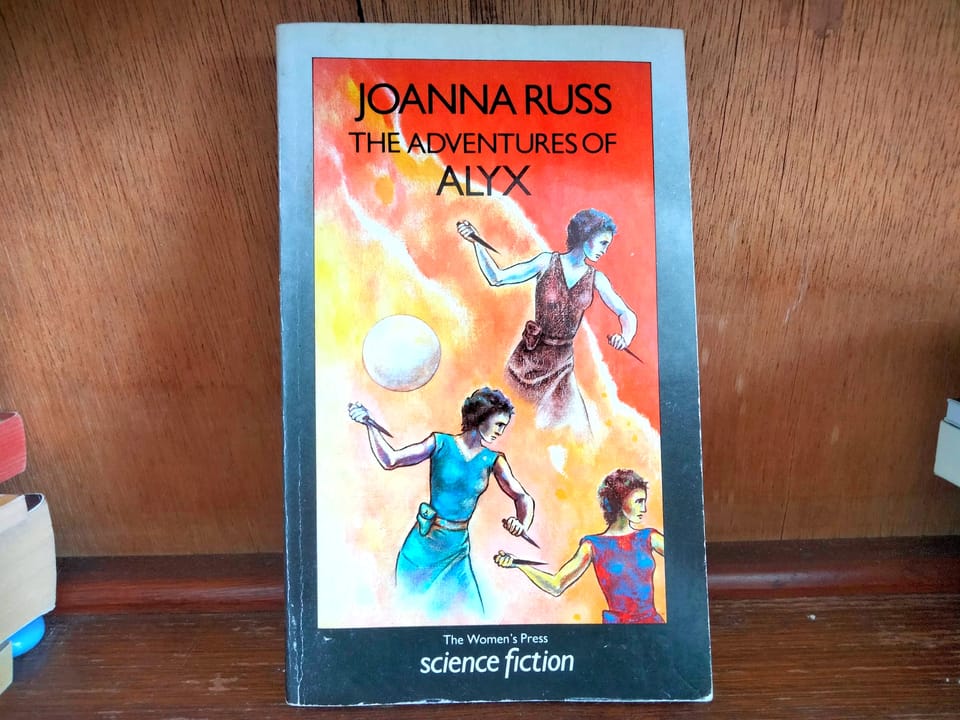

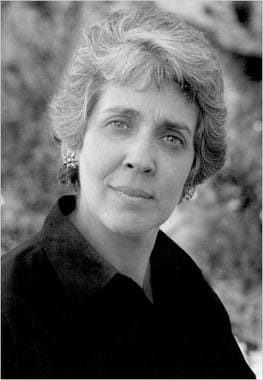

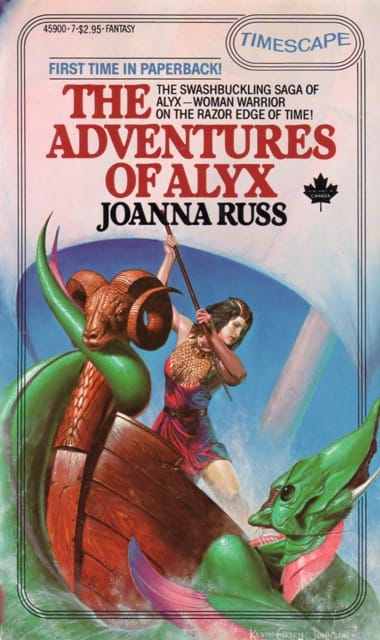

Here's another example: Joanna Russ is a beloved pioneer of feminist science fiction, well remembered for works like The Female Man, We Who Are About To... and How to Suppress Women's Writing. I have not read any of these. But I have read and loved her early collection of sword and sorcery tales, The Adventures of Alyx (1976).

So on the one hand, I'm not well qualified to talk about Russ's work overall. But on the other, there might be some value in starting at the beginning of her career and working my way forwards.

The Adventures of Alyx is a brilliant, restless collection of five stories that follow a wandering thief and adventurer: “wit, arm, kill-quick for hire” is how Russ describes her in the third story. At first, Alyx seems like a straightforward inversion of masculine heroes like R. E. Howard's Conan or Fritz Leiber's Fafhrd and the Grey Mouser. (In the first story, Alyx reminisces about her brief love affair with Fafhrd himself. Leiber returned the favour by putting Alyx into one of his own stories.)

And if that was all this book was—“Conan, but a woman”—it would have been cracking good fun. But Russ is not satisfied to stop at this. With each story, she seems to look back on the previous one and ask, “But what if…?”, deconstructing her own work, until the final piece in the collection is practically unrecognisable from the opening.

Alyx is never quite the same Alyx as before. And the world she inhabits is similarly unstable. Sometimes she is in a fantasy city (“Ourdh, where all things are possible”) but other times she is placed in a historical context by scattered references to real locations. The first two stories give conflicting accounts of her origins: in one she’s a kind of ex-cult member, in the other she’s escaping from an abusive marriage.

The prose in these stories is unique, off-kilter, and occasionally aggravating. Russ has a habit of describing even mundane things in a backwards way that makes them seem alien. Sometimes this comes off as affected and, frankly, a bit annoying. In particular, some of her dialogue is very clunky and hard to follow. But at other times the prose is wonderfully rich, as in this introduction to the florid city of Ourdh: “At night Ourdh is a suburb of the Pit, or that steamy, muddy bank where the gods kneel eternally, making man”.

The third story, “The Barbarian”, is my personal favourite. Actually, it's my pick for the all-time most perfect sword and sorcery story. This one begins with Alyx—now married to a useless but loveable drunk—being recruited by a mysterious benefactor. This man is apparently immortal, and wields an array of magical devices. At various times he implies himself to be a wizard, a time traveller, and even the creator of all life on earth. Only, Alyx doesn't believe him. Because, magic gadgets notwithstanding, he seems to be… kind of stupid.

This tension, between the powerful but foolish wizard and the hard, calculating Alyx, develops wonderfully through the story. It leads to a perfectly pulpy climax, in which (among other things) Alyx overcomes a seemingly impenetrable force-field in a manner that any D&D player would be proud of.

So at this point, Russ has smudged the lines a bit. Gotten a dash of sci-fi in her fantasy. That's not too far out of the ordinary. Fafhrd also had a story where he met an interdimensional traveller. (So did C.L. Moore's Jirel of Joiry, who was Alyx’s predecessor in the field of feminist swashbuckling).

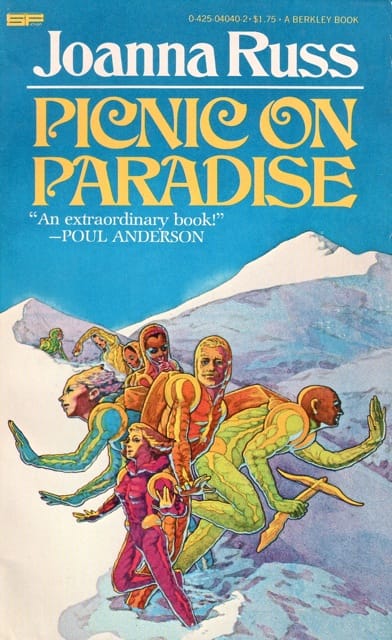

But rather than pulling back from the sci-fi precipice, Russ proceeds to dive in with the fourth and longest story, “Picnic on Paradise”. Here we are flung abruptly into the far future. Alyx has been accidentally scooped up by time travellers and, since they can’t return her to her own time, they instead give her a job that makes use of her unique skill-set.

Once again, the genre and style of the previous story is flipped on its head. Both "The Barbarian" and "Picnic on Paradise" deal with the theme of self-reliance versus technological shortcuts, but through inverse lenses: "The Barbarian" is about a single techno-master in a primitive world, whereas "Picnic" is about a single primitive woman in a world of high technology.

Russ's final flourish, in the last story of the collection, is to discard Alyx altogether. “The Second Inquisition” is told through the eyes of a teenage girl in the 1920s. The spare room of her house is occupied by a mysterious guest, who we soon realise is a time traveller. At one point the guest casually reveals that she is Alyx’s granddaughter. But, wait—this particular conversation is implied to be, maybe, a figment of the girl’s imagination—which would make the guest herself real, but Alyx merely an invention. You can see how the prism of interpretations turns, throwing its light now here and now there…

The overall result of these many convolutions is a collection that feels like a meta-adventure; like we are on a journey through genre with Russ and Alyx by our side. (Ok, it’s possible I just wanted to use this metaphor to justify the cute title of this post.)

These stories were apparently written in a transitional stage of Russ's craft. As she writes in the introduction:

I had turned from writing love stories about women in which women were losers, and adventure stories about men in which the men were winners, to writing adventure stories about a woman in which the woman won. It was one of the hardest things I ever did in my life.

It’s not hard to imagine Alyx as a kind of companion, holding Russ’s hand as she makes her way across this difficult terrain.

The obvious thing to do with this book in 2025 would be to hold it up as a comparison to modern fantasy novels with their stolid devotion to “worldbuilding”—what M. John Harrison describes as “the great clomping foot of nerdism… the attempt to exhaustively survey a place that isn’t there”.

Fantasy writers and readers today are inclined to treat every piece of fiction as a bit of documentary evidence from another world. They want everything to fit together in a rational order, and see any inconsistencies as flaws. Readers seek reassurance of the fictional world's solidity in the form of appendices and supplementary materials that give exhaustive detail on the setting’s history, geography and economics. “Is this canon?” the fans want to know—as if their enjoyment of the story hinges upon the feeling that the events, in some sense, “really happened”.

Conversely, a certain type of highbrow SFF writer is inclined to reject this focus on “canon” as misguided or even regressive. As Vajra Chandrasekera puts it: “Worldbuilding as a totalizing project cannot help but fail…“suspension of disbelief” and “secondary world” [are] not helpful ways to think about what is actually happening when we read a text”.

And it is pretty easy to criticise this attitude, especially in its greatest excesses: for instance, the gnashing of teeth from Star Wars fans when Disney declared a huge swath of their favourite novels to be “no longer canon”; or the transparent attempt at IP-building by Brandon Sanderson as he ties all of his novels together into an enormous meta-universe.

In one sense, The Adventures of Alyx scorns all that. Alyx’s identity is constantly shifting; she’s never the same woman from one story to the next. Russ embraces the unstable nature of the fictional world rather than trying to fix it in place.

But then again—isn't there some point of similarity between Sanderson's worldbuilding and Russ's stories? In both cases, there is an urge to tie the works together into a larger whole. For Russ, the thread that holds it all together is Alyx herself (whereas for Sanderson it's, uh, apparently a bunch of gods and parallel timelines and stuff). There is continuity here, even if it doesn’t continue in the way we would expect from this kind of fiction.

I do believe the illusion of a consistent secondary world is one of the great pleasures that speculative fiction offers us. (I wrote big post tracing the history of “secondary world” as a concept; presumably Chandrasekera would not approve.) If “worldbuilding” becomes grating, it's probably just because the worldbuilding has been done badly. Long lists of dates and events are a boring way to write real history, too.

But what Alyx shows us is that there are many possible forms of continuity, many different threads that can hold a body of work together. I'd like to see more fantasy writers explore those threads, rather than rejecting them outright.

Availability: There is no ebook release for this collection, but old copies are reasonably priced on AbeBooks.

Header image cover art by Judith Clute.

Member discussion