"Behold the Man": Michael Moorcock's Big Middle Finger to Christianity

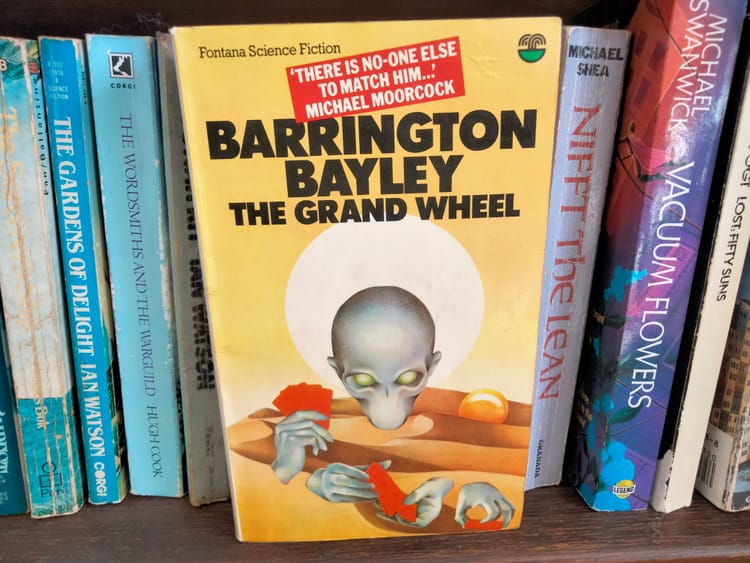

Michael Moorcock, if you don’t already know, is a great author. Though he has never quite broken through to mainstream popularity, he has had a huge influence on science fiction and fantasy throughout the latter half of the 20thcentury. He is, as they say, your favourite fantasy writer’s favourite fantasy writer. I myself can heartily recommend a good number of his books, from the lush and pulpy Corum novels, to the decadent amorality of The Dancers at the End of Time, to the balls-out anarchic madness of the Jerry Cornelius series (which is likely to feature in a future edition of this blog).

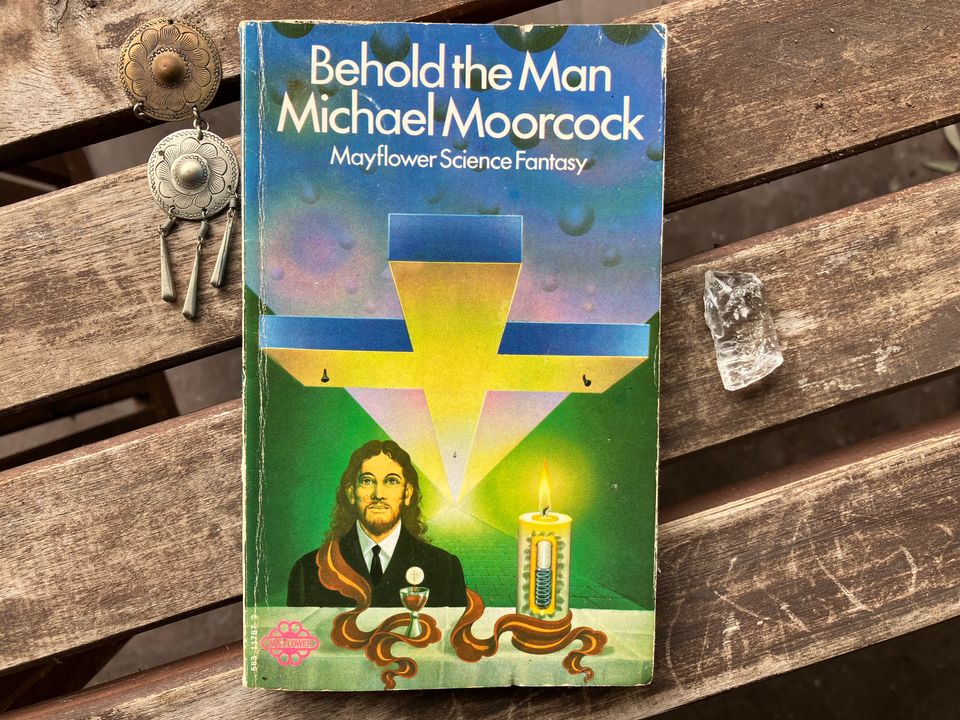

Unfortunately, I cannot extend that recommendation to Behold the Man (1969), a mean-spirited and poorly written screed that offers little beyond facile, juvenile aggression toward the Christian faith.

A warning: this is a novel that has a big secret, and it’s pretty much impossible to discuss the text without revealing it. So turn back now if you don’t want this 60-year-old novel spoiled for you. Also, please be advised this post contains some discussion of sexual assault.

Behold the Man begins with a 20th-century man, Karl Glogauer, travelling back in time to the early 1stcentury A.D., in Judea. The narrative then alternates between Glogauer’s adventures in the past and flashbacks (or flash-forwards, depending on how you look at it) to his childhood and teenage years in the 20th century.

It soon becomes clear that Glogauer has come to the past in search of the historical Jesus. He has studied ancient Aramaic for six months, which is apparently enough to let him communicate easily with anyone he meets. After being pulled from his busted time machine by the Essenes, he drifts between various religious communities, and makes friends with John the Baptist. He determines that it is A.D. 28, only a few years before the due date of the Crucifixion. Despite this, nobody he meets has ever heard of Jesus, and Glogauer begins to despair, thinking the entire Gospel narrative might be a mere myth.

Meanwhile, Glogauer’s early life is related through a series of short, chronologically jumbled scenes. He grows up in postwar England, with an absent father and a neurotic mother. He suffers various traumatic experiences, which might have been affecting to the reader if they didn’t feel so generic. There is a scene where bullies beat him up, another where he is whipped by a sadistic camp counselor, and a third where his mother has a nervous breakdown. Most of these scenes are less than a page long and some are only a couple of sentences, so there is little room for emotional investment to grow.

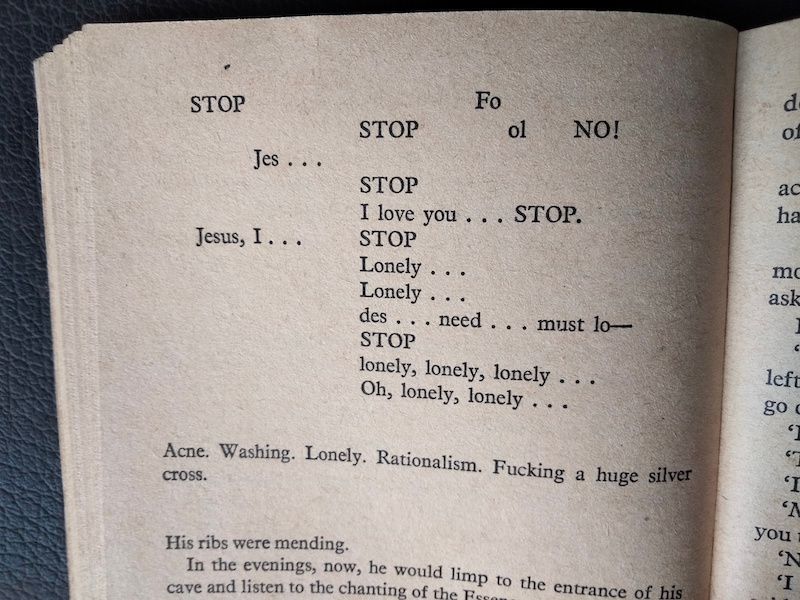

This must have been a deliberate choice by Moorcock, who is capable of writing richly textured scenes when he wishes. Behold the Man was written at the height of the science fiction New Wave, in which authors like Moorcock, Samuel R. Delany and M. John Harrison were incorporating literary techniques from Modernism, Surrealism and other movements to tell SF stories in new ways. Moorcock here seems to be drawing on the Modernist tradition, as he stitches together snatches of dialogue, stream-of-consciousness writing, and exotic formatting. But there is an embarrassing clumsiness to the way he uses these techniques. These are methods that were mastered decades earlier by literary authors like E. E. Cummings and William Faulkner. Moorcock’s efforts are kid stuff by comparison. Here he is shuffling words all over the page like a total dork:

And here is one of his crude attempts at poetry (line breaks in original):

Plonk.

Across all the deserts of Arabia I made my way, a slave of the sun, searching for my God.

‘Time and identity, the two great mysteries…’

Where am I?

Who am I?

What am I?

Where am I?

T. S. Eliot it ain’t.

It doesn’t help that Glogauer is a horribly unlikeable character. In his teenage years we witness an ugly scene of him trying to force himself upon a girl who rejects him. This experience is so humiliating for him that he develops a Freudian fixation upon the silver crucifix pendant that she wore around her neck (or, as Glogauer puts it, “between her breasts”).

Subsequently, silver crucifixes become a fetish object. We are treated to a squalid scene where he masturbates while imagining himself “fucking a huge silver cross.” Later on, he is sexually abused by a Catholic priest, in a church beneath a wooden cross. These two experiences lead him to develop a fetishistic schema in which: “Silver crosses equal women [and] wooden crosses equal men.” There follow some bizarre visions of wooden crosses pursuing silver crosses as the boys of Glogauer’s world pursue the girls.

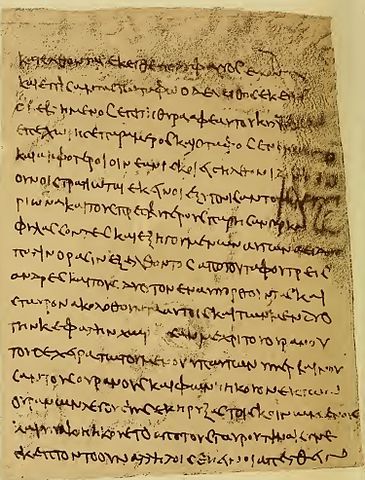

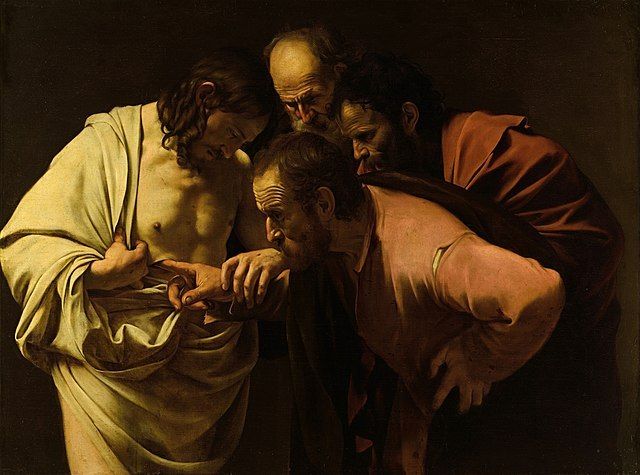

As an aside, this idea of crucifixes having human-like agency does have some precedent in Christian writing. The 2nd-century apocryphal Gospel of Peter describes a cross that moves and speaks as it exits the tomb alongside Christ himself:

… again they see three males who have come out from the sepulcher, with the two supporting the other one, and a cross following them… and they were hearing a voice from the heavens saying, ‘Have you made proclamation to the fallen-asleep?’ And an obeisance was heard from the cross, ‘Yes.’

A similar theme appears in the Old English poem “The Dream of the Rood”, in which the cross speaks and recounts its own experience of the Crucifixion:

With dark nails they drove me through: on me those sores are seen,

open malice-wounds. I dared not scathe anyone.

They mocked us both, we two together. All wet with blood I was,

poured out from that Man’s side, after ghost he gave up.

Is it possible that Moorcock was inspired by these texts? I really don’t know. Actually, I just like quoting weird Christian writing. Let’s move on.

As an adult, Glogauer wanders around Europe in an existential daze, hanging out with counterculture freaks (including a friend who “get[s] terribly randy watching black masses”, and a group of Neopagans who believe themselves to be the lost descendants of Atlantis). Glogauer is Jewish by birth, but becomes obsessed with Christianity. He longs to find meaning in a world unmoored from faith and tradition.

Then one day he meets a guy who has a time machine.

It’s really as simple as that. There’s a guy at the local Jung reading group who quite casually mentions he has invented time travel: “I’m doing all sorts of spectacular experiments at the moment. Sending rabbits through time, that sort of thing.” So Glogauer checks it out, finds that it’s real, and decides to go back in time to find Jesus. And off he goes. That’s the end of the present-day storyline (though unfortunately there are still more dreary flashbacks peppered through the book right until the end.)

Meanwhile, in the 1stcentury, Glogauer has still found no sign of his Lord and Saviour. So he makes his way to Nazareth and asks around until he finds Joseph and Mary. “I wish to meet one of your sons. Have you one called Jesus?” he asks them. They say they do. But to Glogauer’s horror, he discovers that the real Jesus is—in Moorcock’s own words—a “congenital imbecile” who has “spittle hanging from his chin” and “giggle[s] as its name [is] repeated”.

As if this combination of juvenile blasphemy and callous ableism isn’t enough, Moorcock immediately attempts to one-up himself. The local Nazarenes make it clear to Glogauer that Mary has been sleeping her way around the town. Later that evening, while Joseph is away on business, the dazed Glogauer returns to Mary’s house and has sex with her—while the disabled Jesus watches through a doorway with “a vacant grin on his face”. Charming!

To be clear, I am not a Christian. I have no problem with works that criticize, even excoriate the Christian faith and its institutions. But it must be done well. It must have something serious to say about belief, morality, hypocrisy, truth. In Behold the Man there is none of that, only offensiveness for the sake of offending. “Fuck you mum, fuck you dad! I’m writing a book where Jesus is disabled and Mary’s a slut!”

Moorcock’s provocations would be more acceptable if they felt like they were driven by genuine anger. Certainly there are many people who have good reasons to say “fuck you” to Christianity, from the victims of child sexual abuse by Catholic priests, to the many LGBT+ people whose lives are threatened by the rampant bigotry of American fundamentalism. But Moorcock’s gripes with the faith seem to be more philosophical than personal. His attitude is less of a revolutionary, hurling bombs at a hated institution, and more of a demolition expert knocking down a derelict building that has already been condemned. “God was killed in 1945,” quips Glogauer’s girlfriend Monica, and later: “God’s corpse is really beginning to rot now.” She says this while watching a Christian TV show that she considers tacky. And that seems to be Moorcock’s biggest issue with the faith: not that it’s cruel or corrupt or oppressive, but that it’s (in the modern parlance) cringe.

Stunned after the revelation of Jesus’s true identity, Glogauer begins wandering the desert in confusion. Some people take him in and begin to view him as a prophet, especially after he correctly predicts the execution of John the Baptist. This leads to the novel’s big twist. There’s a good chance you’ve guessed it by now anyway. In the absence of a real Jesus, Glogauer slowly accepts that he must become Christ.

This might have produced some interesting scenarios: if there is no divine force involved, how will Glogauer recreate the Gospel story with all its miraculous events? But Moorcock answers these questions in the laziest, most slipshod manner imaginable. How did Jesus cure people of blindness and disease? Well, he took a few semesters of psychiatry, and most of their illnesses were just “hysterical conditions” anyway. (Lazarus isn’t mentioned, so we’ll have to assume he was suffering from a case of hysterical death.) What about walking on water? That one’s easy: “Once he preached to them from a boat, as was often his custom, and as he walked back to the shore through the shallows, it seemed to them that he walked over the water.” It’s as simple as that!

There is a weird kind of temporal bigotry going on here. Moorcock imagines the people of the 1stcentury as being so ignorant and gullible that the mere presence of a modern person—even a neurotic wimp like Glogauer—would be enough to wow them into forging a belief that would last two thousand years.

As he approaches Jerusalem, Glogauer begins stage-managing his own death in accordance with what he remembers of the Gospels. There is a pretty funny scene where he selects his twelve Apostles based entirely on their names: “Is there a man here called Peter? Is there one called Judas?” But this flippancy reveals how little Moorcock really understands about the dawn of Christianity. The Twelve Apostles were not just some random guys. They were the founders of the religion. It was their visions of the Resurrection that inspired them to preach that Jesus Christ was God. Their unshakeable conviction of this fact—often in the face of persecution, torture and death—was what pushed Christianity from one among dozens of Messianic cults to a proselytising religion that would grow to be the world’s largest. (For more on this subject, see Bart D. Ehrman’s excellent book and lecture series, How Jesus Became God.)

Moorcock dismisses the Apostles and ignores the Resurrection, not even bothering to give a fake psychological explanation for it. As a result, his deconstruction of the Christian story is deeply unconvincing.

There is one more big blasphemy thrown in before the end. In a near-psychotic haze, Glogauer acts out the last days of Jesus Christ and is sent to the cross. When they put the nails through his hands and feet, he has a vision of: “the little silver cross, dangling between the breasts, the rough wooden cross advancing.” And then he gets an erection.

That’s right folks. Jesus popped a boner! Gives a new meaning to the Passion of the Christ, am I right? But seriously, this book is terrible.

The final scene reveals that Christ’s famous cry: “Eli, eli, lama sabachthani” is actually English words: “It’s a lie—it’s a lie—it’s a lie…” No, that doesn’t even really match up phonetically, but at least it sums up Moorcock’s opinion pretty clearly.

The problem is that even in 1969, this opinion wasn’t particularly clever or novel. Whether you are a believer or not, there are so many more interesting things to say about the Christian faith than, “Eh, it’s not real.”

Member discussion