Eden Among the Stars: Pauline Gedge’s “Stargate”

Does all fantasy fiction owe its existence to The Lord of the Rings? Ask any serious fan this question and they will likely bristle. Anyone who has read Piranesi or Black Leopard, Red Wolf or Gormenghast will be irritated, if not outright offended, by the implication that the entire genre amounts to no more than faded photocopies of a single original text.

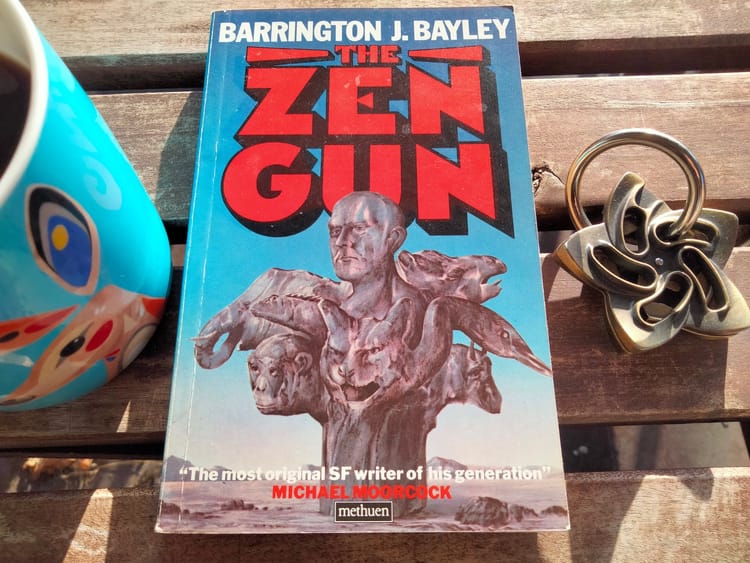

Yet nobody can deny Tolkien casts a long shadow. Writers like Terry Brooks and Robert Jordan have made millions by imitating him. Others, like Michael Moorcock and Steven Erikson, have consciously striven against him. But there are few who have gotten away from him altogether.

If Tolkien’s influence is like a stream, then Pauline Gedge’s Stargate (1982, no relation to the 2000s TV series) is a novel that floats with the current, neither resisting the flow nor sinking beneath the surface. It does not copy the superficial tropes of The Lord of the Rings—there are no elves or dwarves to be found here—but it dwells on the same themes as that novel: time, grief, corruption and redemption. Like Tolkien, Gedge is concerned with Good and Evil, capital G and E. They are objective forces in her world. But like Tolkien, this does not prevent her from exploring how both forces can be mingled within a single character.

In Stargate there are, in fact, no evil characters who were not once good. And when the last heroes fall to darkness, it is not because they were overwhelmed from without, but eaten away from within.

The novel’s plot is grand and cosmic in scale, telling of the decline and fall of a race of immortal beings known as sun-lords. Much like angels (or the Maiar in Tolkien’s cosmology) the sun-lords were set in place at the dawn of the universe. Each presides as a god over their own home planet, in which suffering is unknown. But now corruption has crept into this galactic Eden. The sun-lords’ own creator, the Worldmaker, has turned against them and is devouring star systems one by one.

There are no invading space fleets here; the threat is not physical, but moral. The Worldmaker cannot reach the sun-lords directly until they fall under his insidious influence. His power, “the black fire”, spreads through a process that is poorly defined but vividly described. It attacks each individual through their own personal weakness: fear, temptation, anger, despair. When the sun-lord succumbs to these forces, their home planet suffers a similar collapse. The sun-lords have tried to prevent this through a program of social distancing—retreating from one another, and aggressively sealing off the Gates to any worlds that show signs of infection. The effort has not been going well: the universe began with one thousand worlds, but by the time of the novel’s opening only five remain.

The downfall of these last worlds begins with another Tolkien staple: a magic artifact that offers power at a terrible price. Here it is not a ring, but a book: The Book of What Will Be In The All, a forbidden tome containing records of the future. Like the One Ring, the Book passes from owner to owner by mischance, corrupting each one in turn. And much as the One Ring famously grows and shrinks to seek its desired master, the Book has the eerie ability to open onto whatever page will cause most darkness to enter the reader’s heart.

Within Stargate’s thematic world, time and corruption are always intimately linked. Time moves differently for the sun-lords precisely because they are immortal, unchangeable. Days pass in their council hall while months or years go by for their mortal subjects. Occasionally time is described as a physical force: “He [Ixelion] felt them also, the seconds, falling delicately against him like blown feathers, drifting around him, seeking a way to enter him and change him.” The sun-lords were created perfect, and therefore immune to time; any change is corruption. “I can never go back,” Ixelion muses at a later point, “for to go back implies that I am not as I once was. My wholeness has therefore become hollow like a shell.”

To read the future in the Book of What Will Be, then, can only bring catastrophe. Eden is a timeless place, an eternal present. Once time begins to pass, it is Eden no longer.

The novel’s storyline moves somewhat awkwardly between several different sun-lords, each falling to the Book in their own way. But the novel’s most compelling character is undoubtedly Ghakazian: a brooding, tormented, paranoid angel who rules over a planet of winged and wingless humans. Ghakazian’s fall from grace is a classic example of the law of reversed effort: he tries so hard to fight the Worldmaker’s advances that he flies—indeed hurls himself—right into his enemy’s clutches.

After coming into possession of the Book of What Will Be, Ghakazian reads a prophecy that his sister Sholia will soon betray him to the Worldmaker. Desperate to strike first, Ghakazian looks for a way to send an invasion force across the galaxy to Sholia’s homeworld. In general it is not possible for mortals to travel through the Gates to other star systems. Ghakazian finds a loophole, however: mortals can pass through a Gate if they are ghosts.

How do you make an army of ghosts? Well, you just have to kill a bunch of people, of course.

Ghakazian’s people have never before experienced physical death. They do die, but only by painlessly separating from their bodies at a pre-appointed time. In a gruesome scene that echoes the tale of Cain and Abel, Ghakazian introduces real death to his world by dropping a wingless shepherd out of the sky. The innocent Ghakans’ reactions to the corpse, its bloody physicality and foul smell, signal the end of innocence for this world:

“Tagar, Tagar, why do you not get up?” she asked. When she received no answer, she squatted, and then she saw the blood, pooling crimson under his head. She touched it gently, wonderingly, still caught in a more merciful time, but Natil, after once glance, understood… Something had fallen from the sky, tearing apart the dream from the reality, and he would sleep no more.

It gets far worse. Ghakazian stokes racial resentment among the winged humans, convincing them to commit aerial genocide against their wingless brethren. And after all this, Ghakazian realises he will also have to kill his own physical body to pass through Sholia’s sealed Gate. There follows an excruciating sequence of attempted suicides:

He brought his wings forward and wrapped his arms around them, holding them tightly before him, and then he jumped… he loosened his grip on his wings for just a moment, a reflex of preservation, but it was enough. Of their own accord the wings flapped back and spread, and he found himself hovering in tight darkness, rock enclosing him.

[…]

For a long time Ghakazian tried to destroy his body. He jumped from a dozen heights. He made fire and plunged into it, but fire could not hurt him. He lay beneath the water of a river, gulping and breathing coldness and a taste of greenness, but he was Ghaka, earth, fire, and water, air and mountains, and Ghaka, sick though she was, knew him and would not harm him.

At last, unable to do the deed, Ghakazian turns to the only one who can help him: the Worldmaker himself. His downfall is complete.

This, and other similar character arcs in the book, are not even close to realistic. These are characters as symbols, cosmic dramas projected onto the largest possible backdrop. As a result, the grand sweep of the story is compelling, but the blow-by-blow details are often unconvincing. The sun-lords are frustratingly passive in the face of their own destruction; they put off decisions until it is far too late, and then give in without a murmur of resistance.

It’s not uncommon for a lazy writer to bend the rules of their own story to get their characters out of difficult situations. You know how it goes: an unexpected ally shows up to save the day. A threatening villain turns out to be toothless. A jail guard falls asleep conveniently near to a cell door. Gedge actually pushes things in the opposite direction, repeatedly breaking the rules to push her characters deeper into the hole. At certain points, this works to produce a sense of terrible inevitability, a fated doom. But most of the time it just feels cheap.

Gedge (who I believe is still active today) is primarily a writer of historical fiction. Perhaps it’s this background that led her to deliver something rather rare in the fantasy genre: a tragic ending. There are some twists and turns, but ultimately the novel ends with the last of the sun-lords passing away into corruption and mortality.

Historical fiction lends itself to tragedy. It is, fundamentally, a genre about things that have passed away. We can imagine a hazy happy future for characters in fantasy worlds; it is much harder to do so for people in the real one, when we can see the ruins of their cities and walk on the earth in which their bones are laid.

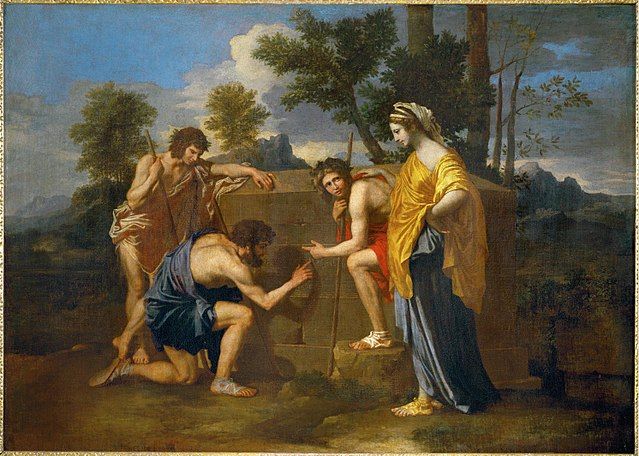

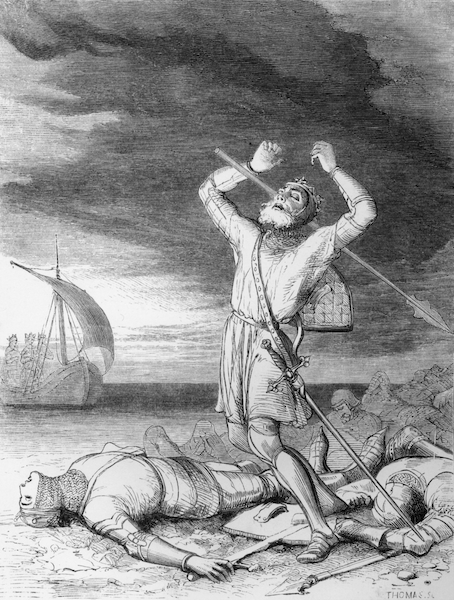

By contrast, fantasy novels tend to offer upbeat endings. Even an ostensibly grim and realistic story like Game of Thrones couldn’t help but conclude with “everything will be alright now, at least for a while”. This trend is a little puzzling when so many of the old sources for the genre are decidedly melancholy. Think of Beowulf dying alone against the mighty dragon; King Arthur slain by the spear-cast of his own bastard son; or Cú Chulainn mourning the necessity of killing his bosom companion Fer Diad. History’s epics looked death and decay squarely in the eye.

Why do fantasy writers no longer do this? Perhaps it reflects a broader trend in the modern world toward progress-fetishism and the denial of death. Or perhaps—like so many things good and bad—it can simply be blamed on J. R. R. Tolkien.

Michael Moorcock, in his famous 1978 essay “Epic Pooh”, accused Tolkien of “ignoring death” and “forcing [a happy ending] on us—as a matter of policy”. Tolkien himself was hardly shy about this agenda. Although The Lord of the Rings draws deeply on European saga literature, it has a distinctly Christian ending, which Tolkien described as a “eucatastrophe” (a portmanteau of Greek words that translates roughly as “good conclusion” or, indeed, “happy ending”).

For Tolkien, the happy ending was explicitly connected to Christian evangelism. He sums up this connection in his essay “On Fairy-Stories”:

The Birth of Christ is the Eucatastrophe of Man's history. The Resurrection is the Eucatastrophe of the story of the Incarnation. This story begins and ends in joy…There is no tale ever told that men would rather find was true.

As I wrote at the top of this post, The Lord of the Ringsis a novel deeply concerned with grief. Few words in English capture the essence of loss as plainly as the Lament for the Rohirrim: “Where now the horse and the rider? Where is the horn that was blowing? Where is the helm and the hauberk, and the bright hair flowing?” But this is ultimately a grief consoled by the presence of a just and loving god.

There is no such god in Stargate. And there is no eucatastrophe that rescues the sun-lords from the relentless march of time.

No-one would ever argue that this obscure and rather creaky novel could match Tolkien’s work for breadth, vividness or originality. Nevertheless, it resists the formula he laid down in favour of an older, darker view of the world. In this sense, Pauline Gedge might be said not only to have drawn upon Tolkien, but to have overcome him.

Further Reading

Here’s a new section of the blog, where I’ll post links to other blogs, essays and videos on the subject of weird or unusual books.

- In the itch.io zine TOWER, Raquel S. Benedict has a delightful review of Bear by Marian Engel, the notorious Canadian literary novel about a woman who has sex with a bear. Benedict does a great job of teasing out the serious themes lying beneath the lurid premise.

- On YouTube, Austin McConnell has a very entertaining summary of the 2nd century fantasy-travelogue True History—although his argument for christening it the “first space opera” is perhaps a little unconvincing.

- RPG designer Ben Milton reviews the book with a multiplayer first-person shooter inside.

Lastly, if you’ve got an opinion to share, or a weird book you think I should know about, you can find me on Twitter @roguesrepast, on Cohost @willgreatwich, or email me at paperbackpicnic@gmail.com.

Member discussion