Rage and Revenge in Aboriginal Australia’s First Fantasy Novel

Content warning. This post contains discussions of sexual violence, racism and genocide.

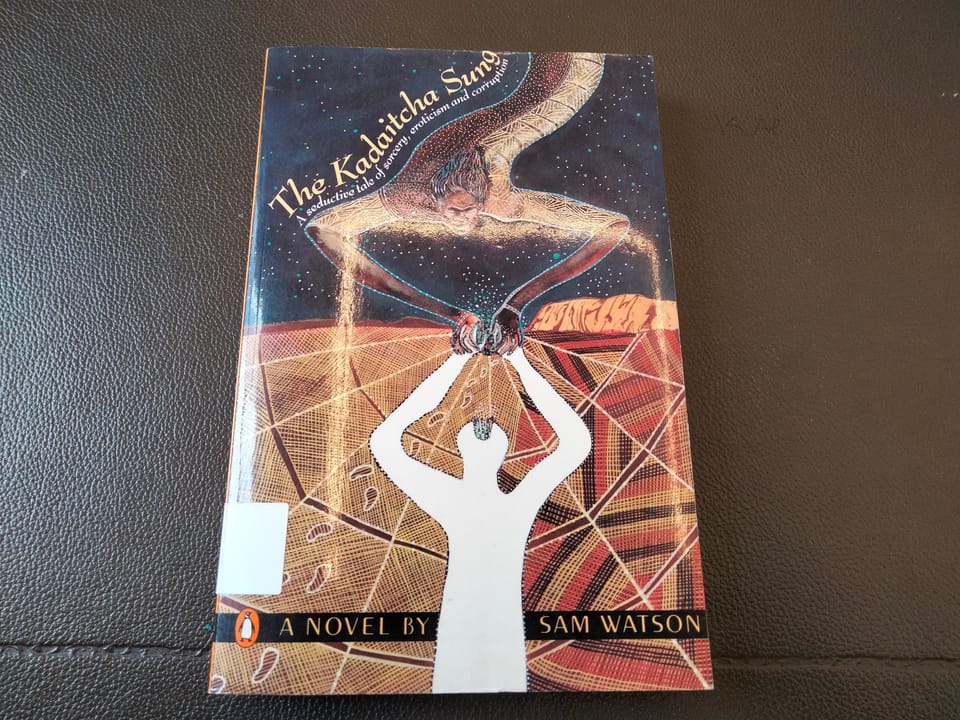

For a white Australian, it is not easy to write about Aboriginal culture, literature, or history. The shame of our colonial past is still too fresh. The blood still stains the land on which we live and work. So it was with some trepidation that I approached Sam Watson’s The Kadaitcha Sung (1990), a bloody fantasy novel that plunges into the heart of colonial violence past and present. It was a confronting novel for me to read, but a powerful one. More than any other Indigenous text I have read, it expresses a pure and unyielding hatred for white European society. But The Kadaitcha Sung is more than just a howl of rage: it is also a complex, nuanced depiction of Aboriginal culture, and a vividly realised piece of fantasy fiction.

The Kadaitcha Sung tells the story of Tommy Gubba, an Aboriginal man living in Brisbane in the late 1980s. As the last of a clan of sorcerers, Tommy has been raised from birth for the special destiny of killing his uncle Booka, who long ago betrayed the clan and slaughtered Tommy’s ancestors.

It’s a classic fantasy premise in many ways: magic, justice, a chosen hero. Yet even calling this book “fantasy” requires some justification. It is clear that Sam Watson was not writing in the tradition of the western fantasy genre. A member of the Birri Gubba people of present-day Queensland, Watson spent most of his life working as an activist and campaigner for Aboriginal rights. The magical elements in his novel serves a political purpose: they affirm the strength and vitality of Aboriginal culture in the face of colonisation.

In Australia, it is generally considered offensive to describe Aboriginal sacred stories as “mythology”. This is a word that implies something dead, unreal, no longer believed. Likewise, “fantasy novel” usually means something made up for entertainment, which is not exactly accurate here. Still, Watson has applied his own imagination, blending together stories from different Aboriginal peoples along with completely new elements. For this reason I would tentatively describe The Kadaitcha Sung as the earliest fantasy novel by an Aboriginal author.

Much like many western fantasy novels, The Kadaitcha Sung opens with a prologue. This tells the story of the Kadaitcha, a clan of sorcerers in the pre-colonial Dreamtime. When the first son Koobara is chosen as the next leader of the clan, his brother Booka is driven into a jealous rage. As part of his revenge, Booka casts a spell that removes the veil of mists surrounding the Australian continent. Because of Booka’s treachery, European explorers are able to discover Australia, and the horrors of colonisation begin.

This opening is surprising because it reverses our normal understanding of blame and agency in the colonial story. It’s not the Europeans but the Aboriginal sorcerer who is the ultimate source of evil. But this hardly lets white people off the hook. Indeed, it reveals an even deeper level of contempt for the whites, who are depicted as mindless brutes barely conscious of their own actions. “They don’t have any deep feelings at all about the land,” says Booka. “They don’t have any great regard for each other, so they don’t draw any power from each other… They are driven by a restless sort of energy that sends them onwards. They are ruled by greed… greed and an evil sort of hunger that won’t allow them any peace.”

After this prologue, we arrive in the post-colonial misery of Brisbane in the 1980s. Tommy Gubba’s magical war against Booka is set against the backdrop of ‘Coontown’, the Aboriginal quarter of the city (likely based on the real-life suburb of Fortitude Valley). This is a squalid world of “lice-infested tenements” and “diseased brothels”, whose streets are lined with “blurred faces dulled by cheap wine and starvation”.

If it weren’t already clear, The Kadaitcha Sung is not an easy novel to read. Aside from the omnipresent spectre of racism, there is a steady flow of violence, rape and misogyny. The despair of a colonised people seeps into every passage and scene. Yet this despair is balanced by a quiet determination to survive.

Watson makes no attempt to sanitise the lives of Aboriginal people. His characters drink, fight and fuck to excess, seizing pleasure from the jaws of oppression. The text is peppered with Aboriginal slang, mostly vulgar: “scrape” for sex, “gumbey” for women, and “buddoo” for penis. But the most common piece of slang is “migloo”: a scornful term for white people.

The book’s most vivid sequence covers a single Friday night in the city. Here Tommy drifts in and out of bars, hooking up with women, meeting friends fresh out of jail, borrowing money and cigarettes, and starting fights with white men. In the midst of all this, he takes time out to kidnap one of Booka’s lieutenants, magically transporting him to Uluru for judgment by a crowd of vengeful spirits. Meanwhile, down the street, the Irish lawyer Jack Finlay is trying to track down some Aboriginal women who have been snatched by the cops.

Violence and sex, fear and desire surge together through this whole sequence, which viscerally conveys the paradox of life as an oppressed minority. Watson’s characters refuse to be ashamed of seeking pleasure, even in the midst of encroaching surveillance, state violence, and death.

The novel’s fantasy elements run in parallel to these realistic scenes. Magic in The Kadaitcha Sung is rich, eerie, violent and grotesque. Body parts and bodily fluids figure prominently. In a particularly gruelling scene, Tommy allows himself to be raped so he can acquire the “sacred juices” of his enemies—the sorcerer Booka and his lieutenant Sambo. Later, Tommy will use these juices to curse Sambo to a slow and painful death.

Elsewhere, the magic walks a fine line between body horror and bawdy comedy. At one point Tommy conceals a magic stone by hiding it inside his scrotum, commenting laconically that “he would have three balls for the next few days”. In another scene, Tommy treats a white woman whose anus has been cursed by her ex-boyfriend:

With both hands he [Tommy] eased apart the soft flesh of her buttocks and smiled. The Island man had used an invisible dart that had entered Sugar through her back passage. The vibrations of Tommy's moogi stone had caused the bruised lining of the anus to light up with a pale glow…

The intervention only took a short time. Tommy carried his poorie bag with him everywhere and he only needed a single bone to break the spell and free Sugar. He sang a low song, burnt a pair of red leaves and passed the bone over the pale flesh beneath him. In a matter of seconds Sugar's body relaxed and her breathing steadied. Her life was again her own. The broken piece of stingray-barb, now cold and completely harmless, popped out of the woman's anus.

But the main purpose of Tommy’s magic is to take revenge: not only on his uncle Booka, but also on all the white people or “migloo” who have despoiled his land.

Colonial violence casts a long shadow over the world of The Kadaitcha Sung, reaching forward from the past into the present. Several scenes present conversations between white rural police officers, who reminisce fondly about massacring Aboriginal children, poisoning water holes, and being paid by the head for genocide during the Black War in Tasmania. Watson is employing some poetic license here: the Black War ended in 1832, which would make these officers over a hundred years old.

Watson discusses this device in a 2003 interview:

The reason I structured the book that way is that Aboriginal people have a very fluid sense of time. So in our culture we don’t really look at past, present and future in a way that other people do. All we look at is an ever evolving present with tensions and events from previous lives that have shaped and impacted upon the life we are leading now… so when you look at my book and you think, well everything happens here within only two days, really what is told is a hundred thousand years of actual history, one hundred thousand white men’s years.

The compression of time is a narrative device that conveys how Australia’s past still haunts its present. For my Australian readers, the statistics are probably already familiar, but they always bear repeating. Indigenous Australians’ life expectancy is nearly 9 years less than that of non-Indigenous Australians. Indigenous men are seventeen times more likely to be incarcerated, a rate roughly double that of Black men in the US. Discrimination and generational trauma still plague Indigenous communities. Last year, a national referendum proposing modest reforms to help Indigenous people was roundly defeated at the ballot box, but not before unleashing a surge of racist rhetoric in the national press and social media.

In the face of such suffering, it is surprising that the majority of Indigenous people seem resolutely committed to reconciliation. It is relatively rare to read Aboriginal writing that expresses anger directly. Political statements focus on ideas like “moving forward together”, “healing”, and “closing the gap”. As the Noongar novelist Kim Scott puts it in Taboo (2017): “We were never hungry… for revenge of any kind. Our people gave up on that payback stuff a long time ago”.

It is all the more confronting, then, to read The Kadaitcha Sung, in which the principle of “payback” is affirmed with such vigour. In the moral universe of this novel, wrongs can only be set right by retribution of equal or greater magnitude. Where this payback cannot fall on a single person, it will extend to their entire race. Tommy and his spirit elders both repeatedly affirm that all white people deserve to die for the crimes of colonisation and genocide. Sin is hereditary.

For myself, a white Australian reader, such a perspective is challenging to read. But what truly surprised me was that the same principle is applied just as rigidly to the novel’s Aboriginal characters. This is shown particularly in the case of Jelda: Tommy’s coworker, friend and sometime lover. Repeatedly described as a “warrior woman”, Jelda is held up as a heroic example of what an Aboriginal woman should be, fighting for the preservation of her culture and family.

But Jelda, too, is fated to die for the crimes of her ancestors:

Tommy was touched by an immense sadness. He knew that Jelda had been marked for death and that he was powerless to stop it. For Jelda was of the black possum totem, and her clan had wronged [the creator god] Biamee. Tommy had not been told of the actual crime, and he did not know when or where it had been committed. He even doubted that Jelda was aware that she could be held responsible for some action or deed that may have been carried out before she had been born. Tommy knew only that the people of the black possum were to die.

Nor is Tommy himself unblemished. While Jelda’s family sin is a mystery, Tommy’s is much more obvious: he is the child of an Aboriginal father and a white mother. Although he asserts that every one of the “mongrel-bred” white race must be destroyed, Tommy also grapples with the impossibility of untangling the “good” and “bad” bloodlines from each other. Containing both within himself, he plays the dual role of avenger and victim, doomed to destroy himself as punishment for his tainted blood.

Late in the novel we even learn that Tommy’s mixed parentage is a necessary part of his destiny: “Your mother’s blood reaches back to sorcerers from northern lands… their powers are equal to those of the Kadaitcha.” Only the fusion of Aboriginal and English sorcery is enough to conquer Booka.

This scene and others reveal that underneath its cries of rage, the novel holds a profoundly ambivalent attitude toward whiteness and Aboriginality. At times Tommy heals and protects white women, and accepts aid from the white lawyer Jack Finlay. The possibility of reconciliation is repeatedly raised and left hanging in the air.

The novel’s conclusion, however, shuts off this possibility definitively. Having defeated Booka at last, Tommy is granted a series of wishes by the creator god Biamee. This is what he wishes for:

For every one hundred migloo, there had to be one that would know depthless tragedy and sorrow. That chosen one would be ridden by a hunger that could never be satisfied, that single life would be a lasting sacrifice to the land of the people. It had not been an unreasonable exchange, or so Tommy had thought. After all, the entire black nation had been visited by much horror.

Biamee grants the wish, but rules that “Tommy had demanded vengeance, therefore the migloo must also be allowed payback.”

Stripped of his powers, Tommy is arrested and sentenced to death by a white court. His final statement—the final statement of the novel—is a defiant affirmation of his unending hatred:

‘You have taken my land with gun and poison, and you hold my land with gun and poison… But I say this to you… I say this, that you are like empty shells. You do not have any substance or any guts. I have my strength and my history in my heart and in my soul. I carry them inside me all the time. You do not have that. My land and my spirit are in me and they are me. That is the way of my people and that is the way of my law.

‘And you cannot take this thing from me. Because I am the dirt. I am the rock and the tree. I am the air and the rain. I am the land. And I say this to you migloo: you will be doomed to the end of time to wear the blood of my people.

‘You will carry that scar on your mind and on your body. You will not be able to wash it away. The blood is upon the land until the end of time, and it is upon you until the end of time.’

So this is the last word Watson offers: no reconciliation, no hope of making amends. Only payback upon payback, forever.

And yet: there are still those moments of ambivalence throughout the book, like tiny windows into another possible world.

Watson passed away in 2019. Tributes to his memory described a very different man to the one whose voice comes through in The Kadaitcha Sung. One obituary called him “a man of peace… who reached out to everyone regardless of gender, creed or race”; another described his “vision of a future socialist society in which Black and white communities would live together in harmony and cooperation”.

Watson himself, when interviewed about the novel, struck a much more conciliatory tone:

We can’t attach direct blame to white people who are walking the streets of Australia today for what happened back in 1788… We don’t feel bitterness, we don’t feel we are owed anything particularly by individuals but the people who dominate the capitalist economy and share in the wealth creating area should at least share the responsibility of ensuring that aboriginal people are compensated.

It is hard to reconcile these words with the content of the novel itself. “Bitterness” is absolutely the dominant emotion of the text. And the book very explicitly does attach blame to modern white people for the crimes of their ancestors.

The simplest and easiest explanation would be to say that Watson’s views simply changed over time. His anger may have mellowed over the decades that followed The Kadaitcha Sung. But to me it seems more likely that both sides of the man could coexist at once; that just as in his novel, the contradiction between rage and forgiveness was never fully resolved.

Availability: The Kadaitcha Sung is a rare book. It is not available in ebook format, nor have I found any copies for sale online. A scanned digital copy can be found at the Internet Archive, and physical copies are available in several State Libraries across Australia. An excerpt from the novel can be found in This All Come Back Now: An Anthology of First Nations Speculative Fiction (2022),edited by Mykaela Saunders.

To leave a comment or suggest a weird old book, find me on Bluesky @gnipahellir.bsky.social, on Cohost @WillGreatwich, or email me at paperbackpicnic@gmail.com.

Member discussion